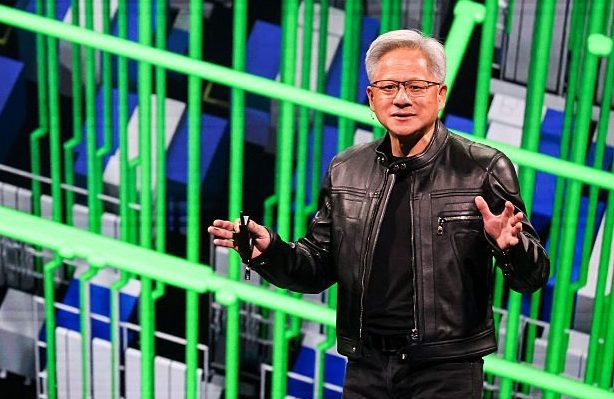

The AI race is a topic that has mostly been kept politely out of the discourse by those in the know. But this week Jensen Huang, CEO of chip giant Nvidia, decided to throw it into the mainstream, with a warning: “China will win the AI race.” The questions of what exactly this race is, what “winning” constitutes, and whether there will indeed be a binary victory: these are all secondary to the messaging. Just like the traditional Cold War races — nuclear, space, computing — this has a feel of do or die.

Huang wants the West to know that AI dominance is just as serious, and cannot be left to chance: it requires an effort akin to the Manhattan Project. He pointed to the fundamentals. “In China, energy is free,” he said, before pointing out that 50% of AI developers are Chinese, and there is a willingness to adopt — to plumb AI into the fabric of life — that is somewhat lacking in the West. Here, it’s worth considering the case of DeepSeek, the Chinese startup that was catapulted to fame with an LLM which delivered a similar performance to its Western competitors for a fraction of the price.

Today, China doesn’t have the chips that make the world go round: high-end graphics cards, capable of many billions of calculations a second, in which Nvidia specialises. The state-of-the-art Blackwell chip is subject to long supply constraint queues, and the Chinese have been put, by White House fiat, at the back of that list. “We will let them deal with Nvidia,” Donald Trump told CBS last week after his talks with Xi Jinping, “but not in terms of the most advanced.”

But, soon enough, China may have something comparable by its own creation. Its capacity to generate high-end phone chips was tested and found to be solid after a previous embargo involving TSMC. Track that line forward and it’s not clear whether the advantages America has today will carry it over the line.

Huang later qualified his comments, saying that he of course wanted America to win; but that will require a clearer strategy than what the US currently has. Encoded in that is a play for government assistance. AI in the US is heavily leveraged. OpenAI has been on a year-long buying and investing spree which has left it with a trillion dollars of potential spending.

The CFO of OpenAI, Sarah Friar, mused this week at the Wall Street Journal’s Tech Live event that the company was “looking for an ecosystem of banks, private equity, maybe even governmental” partners. She then walked that back, clearly not wanting to jeopardise the perception of the company. American AI is at a liquidity crossroads, and many are wondering whether they can tap into the infinite funds that only a federal government contract can supply. They seem to like the analogy with radical Lockheed and Northrop military planes of the Sixties. Indeed, Elon Musk’s Grok signed a $200 million contract with the Pentagon earlier this year. It should also be noted that Tesla, SpaceX and SolarCity have all benefited from an estimated $38 billion in government support, including loans, tax breaks and contracts. Others want a slice of the pie.

Huang is right to believe that China can win some of the AI race. The capacity of a command economy to pivot its resources, especially fundamentals such as electricity generation, loads the decks towards Beijing. And China’s general lack of Western decorum when it comes to data protection and workers’ rights means it may win many battles.

But the keys to strategic dominance won’t come from the next Excel, nor from “smart cities”. They will come from the crowning heights: consumer products that are globally superior, and military uses that operate at the apex of what’s possible. Just as no one would pit IBM’s Kasparov-beating Deep Blue against a modern LLM in chess, even marginal superiority in military matters will have cascading outcomes. On this score, America has a deep well of innovation, as well a far broader scope of engineers and entrepreneurs to draw on.

In one sense, though, the race is not just between two superpowers. It is a race between them and those who aren’t in it. With big leads already established, over the next 30 years the two countries will quickly leap ahead of the rest of the world, leaving the beleaguered tech-desert of Europe in their wake. That is the factor that Huang dared not mention.