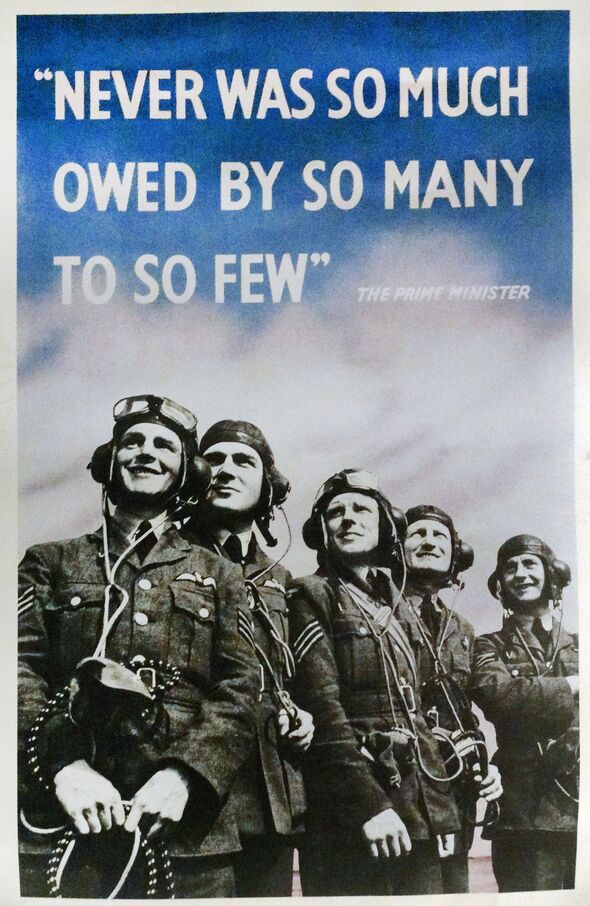

Iconic shot of RAF pilots that was used in famous propaganda poster (Image: Popperfoto via Getty)

Hermann Goering, the obese, drug-addicted commander of the Nazis’ air force throughout the war, was at his most bombastic as he addressed his senior officers in early August 1940 about the forthcoming clash with Britain. Promising that his aerial armada would destroy the resistance of the British, he declared: “I plan to have this enemy down on his knees in the near future.”

Goering’s confidence seemed justified. In almost a year of conflict, the German war machine had proved invincible. Much of Europe was now under its control – and France had fallen with dramatic rapidity. The conquest of Britain, however, was a different challenge. Because of the natural defensive barrier created by the English Channel, Germany would have to gain the mastery of the skies over southern England before an invasion could be mounted.

That meant obliterating the RAF, both at its bases on the ground and through combat in the air. But even on its home territory, Goering believed that defeat of Britain’s air force would be swift and inevitable, especially given the huge numerical superiority of the Luftwaffe, which comprised 4,100 aircraft, including more than 1,500 fighters and almost 2,000 bombers, compared with just 1,900 planes in the RAF – of which less than 800 were modern fighters.

Hitler was so confident of victory that on July 16 he issued a directive to his high command, instructing that detailed plans be drawn up for a full-scale invasion of England once the Luftwaffe had gained air supremacy. Codenamed Operation Sealion, it was a massive undertaking that involved 260,000 troops, 34,000 vehicles and 2,000 troop-carrying vessels.

Germany’s build-up of its invasion forces in occupied France added to the sense that the imminent aerial struggle could decide the future not just of Britain but the destiny of mankind. “Hitler knows he will have to break us on this island or lose the war,” Winston Churchill told Parliament in one his greatest, most prescient speeches. Goering was sure there could be only one outcome. Having fixed the start of his attack for August 13, known as Adlertag or “Eagle Day”, he told his men: “Within a short period, you will wipe the RAF from the skies.” But he had failed to recognise the tenacity of Britain’s defenders.

The Battle of Britain propaganda poster quoting Winston Churchill’s timeless rhetoric (Image: Universal Images Group via Getty)

At this historic hour in our island story, our country found the men and machines to take on the Nazi aggressor. From the start, the resistance of the RAF was far tougher than the Germans had expected. Eagle Day was supposed to be the harbinger of victory but instead was a blood-soaked failure, with the Luftwaffe losing 44 aircraft – more than three times the RAF’s losses of 13 planes.

That set the pattern for the following weeks as the rate of attrition suffered by Germany became unsustainable. “We found the English well-prepared and our job was not an easy one,” recalled the German ace Adolf Galland. In their complacency, Goering and his strategists had ignored three vital assets that made Fighter Command such a potent adversary. The first was the sophisticated defence organisation that the boss of the command, Sir Hugh Dowding, had built up during the 1930s.

He was a socially awkward man with unorthodox beliefs in reincarnation, spiritualism and vegetarianism, but he was a magnificent technocrat. His advanced system enabled the RAF to plot incoming enemy aircraft from reports provided by the chain of radar stations and the observer corps. This intelligence was then filtered down through control rooms to the fighter stations, rather than wasting petrol, energy and time on speculative patrols.

A passionate advocate of fighter defences at a time when the primacy of the bomber was still an article of faith in the RAF, Dowding was also instrumental in the development of the its fast monoplane fighters, the Spitfire and Hurricane. The Supermarine Spitfire, designed by the engineering genius RJ Mitchell, who in the 1920s pioneered record-breaking sea planes, was the more advanced machine. With its graceful shape and record-breaking speed, it became the cherished national symbol of defiance in 1940.

It was also adored by its pilots for its manoeuvrability and the responsiveness of its controls. “There was no heaving or pushing or pulling or kicking. You breathed on it. I have never flown anything sweeter,” recalled the pilot George Unwin.

Spitfires in flight later in the war (Image: Mirrorpix)

The problem in 1940 was that its production had been plagued by difficulties, not only because it was technically complex to build but also because the Supermarine firm, based in Southampton, was unused to mass production. In 1938 the Government tried to get around this difficulty by creating a colossal specialist plant at Castle Bromwich in Birmingham – meant to turn out 1,000 Spitfires by June 1940.

But the factory was hopelessly managed by its boss, the rapidly ageing motor-car magnate Lord Nuffield, and by the target date not a single Spitfire had come off the production line. It was only when Churchill appointed Daily Express owner Lord Beaverbrook as his Minister of Aircraft Production that the plant began to operate efficiently, under new management. Fortunately, by the summer of 1940, Supermarine at Southampton was running properly, and able to make up some of the Spitfire shortfall.

More importantly, the Hurricane, which was simpler to build and available in larger numbers, proved to be deadly in combat. It made up the majority of Fighter Command’s strength and accounted for more than 55% of German losses. But neither of these planes would have achieved much without the unparalleled bravery of the men who flew them, such as James Nicholson, who won the Victoria Cross for his successful pursuit of a twin-engine Messerschmitt 110 despite being in agony from a fire that engulfed his cockpit after it was hit by four cannon shells.

Equally impressive was the near indestructible New Zealander Al Deere. He destroyed 17 enemy aircraft during three months that summer, during which time he was shot down seven times, bailed out three times, collided with a Messerschmitt 109 fighter, and saw his burning plane explode just seconds after he had scrambled from the wreckage.

The RAF’s spirit of determination was also embodied in Douglas Bader, who had lost both legs in a pre-war flying accident but returned to action and shot down 23 aircraft, flying both Spitfires and Hurricanes. Altogether 544 Fighter Command airmen died in the battle – though the total RAF death toll including personnel in other commands was 1,542. As Churchill put it at the climax of the battle: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Don’t miss tomorrow’s Express for Part Four of our 11-part series retelling the story of the Second World War: The Blitz and the Battle of the Atlantic

Yet even as their losses mounted, the Germans continued to underestimate Fighter Command. By early September they had convinced themselves that Dowding’s force was broken, so their bombers were ordered to hit London by night rather than keep hammering the air bases by day.

It was a disastrous strategic error that gave Fighter Command the chance to regroup. When the Germans renewed their daylight offensive on September 15, they were surprised to be confronted by reinvigorated fighter defences. Having suffered crippling losses, they abandoned the struggle.

The British did not yet know it but the battle had been won. On September 17, Hitler indefinitely postponed Operation Sealion. For the German general Gerd von Rundstedt, this was the crucial turning point in the war: “That was the first time we realised we could be beaten – and we were beaten. We did not like it.”

Hitler didn’t bluff: Operation Sealion WAS serious

Conventional wisdom holds that Hitler was never serious about Operation Sealion, the Nazi code name for the invasion of Britain in 1940. According to this narrative, the plan was a gigantic bluff designed to tie up Britain’s resources while the Reich’s high command plotted an imminent attack on its real target – the Soviet Union. Certainly Hitler knew that even with air superiority, the operation would have been extremely risky – especially with Britain’s Royal Navy still intact. Moreover, the Fuhrer privately admitted he had little understanding of maritime warfare.

“On land I feel like a lion, but at sea I am a coward,” he said. Yet there is a wealth of evidence that Sealion was far more than just a paper exercise. For a start, the preparations were extremely thorough, as exemplified by the installation of huge guns at Calais, aimed at the Kent coast, and the collection in the occupied ports of more than 2,300 invasion barges, many of which were converted into troop carriers.

More than 400 tugs were gathered in readiness to pull the lines of barges across the Channel, though the Germans also built the high-powered Siebel ferry to provide transport. A bolder innovation was the creation of 250 Tauchpanzers or submersible tanks, which were waterproofed and fitted with long snorkels so they could travel underwater.

Another amphibious type of tank was the Swimmpanzer, which had sufficient floats to stay on the water’s surface. The Nazis also made sinister plans for the occupation of Britain in the event of victory. The country was to be divided into six economic regions, with order kept by a Gestapo force.

All able-bodied British men were to be sent to the continent to provide forced labour – and Winston Churchill’s birthplace, Blenheim Palace, would become the Nazis’ British headquarters. As a symbol of our subjugation, Nelson’s column would be pulled down and carted off to Germany. Fortunately, the resilience of the British people avoided such a chilling eventuality. Our island nation would remain free.