Chris Hewitt passes me an unattached old-fashioned microphone that looks like a steel ice cream cone. It’s surprisingly heavy. “That’s one of the microphones the Beatles used at Shea Stadium.”

Chris is a ‘let’s do the show right here’ kind of guy. The 71-year-old from Rochdale is a Manchester music catalyst who escapes the notice of the cool media gatekeepers fixated on the city’s famous figures (you know who they are).

He embodies the under-reported role of North Manchester’s boroughs on the music scene, being the driving force behind the 1976 Deeply Vale free festival, which, for four years running, brought together the hippy and punk tribes in a picturesque valley near Bury.

Who is Chris Hewitt?

Chris Hewitt Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

Chris Hewitt Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

“I was asked to leave grammar school in Oldham. They said my education would be better off at a more liberal establishment. So I went to Rochdale College.” What did he study? “Promoting bands,” he wisecracked.

“People like Screaming Warthog and the Pink Fairies. All the bands we read about in Oz or International Times,” he said, citing the underground magazines that stuck it to The Man back in the late 60s/early 70s. “I definitely come from the counterculture. I don’t like rock stars going to the Palace to get their OBE.”

He also assembled the sound system that united Rastas and punks at the 1978 Rock Against Racism festival at Alexandra Park, Moss Side, and he joined Joy Division producer Martin Hannett at the mixing desk for his pioneering adventures in sound.

Chris is not only an unsung mainspring of modern pop culture in Greater Manchester. He is an undisputed expert on live and recording music technology, having written four self-published books on the history of sound systems and two on Hannett, the aural explorer who told Joy Division’s drummer to “make it sound more purple” and recorded the lift in motion at Stockport’s Strawberry Studios.

None of that is the reason fifty or so men of a certain age, and a few women, known as ‘gear heads’, are gathered at a cavernous industrial unit close to the M66 in Bury. They simply want to go back in time and stand, like me, in a faithful, small-scale recreation of Sun Studio in Memphis, USA.

What does Chris have in his collection?

Recording equipment from Abbey Road Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

Recording equipment from Abbey Road Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

“Elvis sang into that mic, Frank Sinatra too,” said Chris of a classic ’50s stand-and-mic set-up. Black and white photos of Sun recording stars like Eddie Cochrane, BB King and Howlin’ Wolf crowd the walls.

Walk through an internal door and you are suddenly in Abbey Road studio. It all feels oddly familiar; the battleship grey metal boxes housing the equipment is recognisable from countless images of the Beatles in the legendary recording location in St John’s Wood, London.

Amplifiers, mixers, reel-to-reel tape recorders with names like RCA, Altec and Echocard surround us. The VOX amps are among his Beatles’ gear. This is the kit the band went back to time and again in the 1960s, leading ‘the British invasion’ into the US mainstream culture and making regional English accents unfeasibly fashionable.

Shea Stadium in Los Angeles was a highlight of their early US tours, when no matter how loudly they sang into the mic I have in my hand, it was drowned out by 55,000 screaming fans.

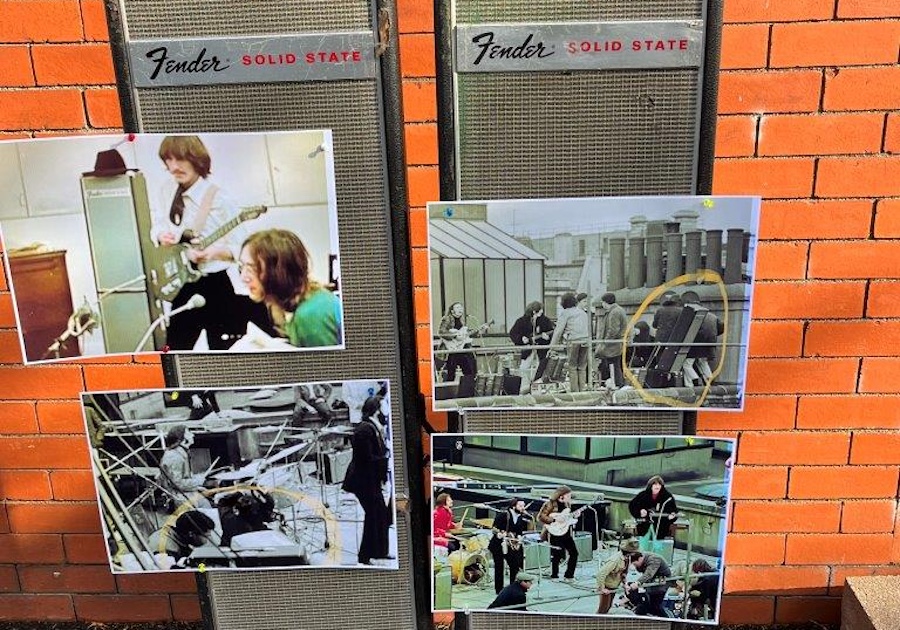

Beatles amps from their 1969 London rooftop show – Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

Beatles amps from their 1969 London rooftop show – Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

For anyone who thinks these may be clever fakes, Chris provides rock-hard provenance. Musicians like Bobby Elliott of Manchester’s Hollies and the Beatles’ George Harrison are pictured with the actual boxes of tricks in front of you.

There is a photo of John Lennon with the “Tittenhurst DBX compressor” used on the

electric guitar sound on Imagine; the video is better remembered for Lennon’s white

grand piano at his Tittenhurst Park home. This stuff has an under-the-radar charisma.

No matter how many retro dials, knobs and sliders it has, a metal box can never be as glamorous as a groovy guitar or a macho drum kit. Chris doesn’t mind. All the fashionable focus on artist memorabilia, evidenced by the BBC’s Antique Roadshow, means Chris can hoover up the gear that studios chuck out when they upgrade.

Strawberry Studios owner Zeb White

Chris paid £70,000 for the Sun studio collection. When Strawberry Studios owner Zeb White died, Chris acquired all its assets at auction, including a bespoke drum kit assembled for Ringo Starr. Goodness knows what he paid for David Bowie’s gold mic used on his Ziggy Stardust tour and Top of the Pops, but he nods when I say it must be worth at least £100,000. The collection’s total value must easily be in the millions.

What’s Chris’ favourite piece in the collection?

Pink Floyd 1971 Live at Pompeii mixing desk Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

Pink Floyd 1971 Live at Pompeii mixing desk Photo credit: Andy Spinoza

His favourite piece is clearly the mixing desk used by Pink Floyd for its 1971 concert movie Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii, not just because the group’s sound engineers, in Chris’s words, “were responsible for shaping the modern PA system,” but because having bought the original shell, he realised he could bring it back to life. His rebuilt 28-channel with six-channel quadrophonic desk works – it was recently used live by tribute act Dark Side at a show in Wigan.

Not only can Chris explain why early British rock bands sounded rubbish live in the States (the UK standard voltage being 240 volts, needing to convert to America’s 110 volts), he has some cracking stories. “Flight cases on tour were waived through air freight customs, so the band and Howard Marks used them to bring his drugs in,” he said. “A bass cabinet was left behind at Montreal airport and a sniffer dog ended all that.”

The Hewitt motherlode resides in deepest Cheshire, where several tennis court-sized units for farm equipment instead contain eye-popping quantities of old amp cabinets, flight cases, trailers and some motor vehicles, like a red 1970s long wheelbase Ford Transit van he hires out to period films.

How does he know there aren’t other rival collections? “The film companies keep calling.” The movie biopics of Freddie Mercury, Morrissey and Elton John came to his collection to get their scenes right. “There were so many music films that were awful, using any old stuff. Bohemian Rhapsody was the first to really care about using the gear that Queen actually used.”

You can’t fool the gear-heads

The Gear Heads Photo Credit Rick X

The Gear Heads Photo Credit Rick X

Now authenticity is critical. “Gear heads can tell,” he said. For the making of Pistol, the Danny Boyle-directed series for Disney+ about the Sex Pistols, Chris recreated two studios and eleven different concerts. On set, he had to advise the young art directors to replace certain bits that were just not around in the 1970s.

He was active in that depressed, angry decade, after all. He managed Rochdale folk rockers Tractor, who set up a studio in Heywood with their advance from BBC DJ John Peel’s Dandelion label. That led to Cargo Studios in Rochdale, where Chris was approached by the Tony Wilson and Rob Gretton, of then fledgling label Factory: “Joy Division recorded at Cargo and I built all theirs, and early New Order’s stage gear. You’re always on that naïve promise that if you do it cheap, they say ‘when we make it big, you’ll get all our work’, which of course they never did.”

Could the collection find a permanent home in Manchester?

Wilson is often cited as a guiding star by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, and Chris tells me he is trying to interest Mayor Andy Burnham’s people in finding a permanent home for the collection.

I get the feeling it’s hard for the hippy-punk veteran, who calls a spade a shovel, to talk the language of civil servants charged with cultural production strategies for the digital age. Yet it would seem daft if Manchester’s visitor destination bosses ignore Chris and his collection.

It has got global gear-head appeal. He recreated the Live Aid scene in Bohemian Rhapsody with the kit used by Queen at Wembley Stadium, and Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason enjoys an annual reunion with his mixing desk for an event at his home.

People travel the world for this kind of thing; look at the global brand that is the Hard Rock

Café, “replica guitars, not authentic,” snorts Chris.

BBC 6 Presenter Mark Ratcliffe Photo credit: Chris Hewitt

BBC 6 Presenter Mark Ratcliffe Photo credit: Chris Hewitt

BBC 6 music presenter Mark Radcliffe was at Chris’s open day. He said: “It’s incredible that the greatest private collection in the world is in a lock-up in Bury. I genuinely think it’s such an important collection; it would bring people to Manchester.

It would be nice to see all this in a proper museum somewhere. I think people would love to see this laid out in the city centre or the outskirts.”

The day after my visit to the Bury drop-in day, the American country digital chart announced the first number one by an AI-generated artist. Breaking Rust sounds gruesome to me, but personal taste aside, it brings into sharp focus that Chris’s bulky metal boxes are the physical remains of our shared pop culture’s means of production.

Today, music is made in the digital ether, often even without using any instruments. Large Learning Model may sound like a Factory band, but it’s the AI training process that enables the hoovering up of music-making, something human beings have loved to do since the start of time.

Will new generations lose interest in the pop culture that changed lives and challenged conventions? Chris Hewitt believes not. He has faith these old cabinets and cases with their knobs and faders exude a magnetic nostalgia, that of the dying analogue age. “Mark Radcliffe saw that John Lennon compressor. He said to me, ‘So Phil Spector and John Lennon have touched this dial, can I touch it, can I get some magic out of it?’

“I said, ‘Mark, you’re an educated man, but it still rocks your boat.”

Find out more about Chris Hewitt’s collection

You can find out more about Chris Hewitt’s musical collection by clicking here