(Credits: Far Out / Album Cover / Justinc)

Tue 18 November 2025 8:30, UK

I can still remember clearly autumn 2003: months earlier, the United States had begun their invasion of Iraq, looking for weapons of mass destruction and England’s golden boy, David Beckham, had been unveiled as a Real Madrid player.

For me, however, that year has a different reason to stick in my mind as it was when I discovered the music of Dylan Mills, otherwise known as Dizzee Rascal.

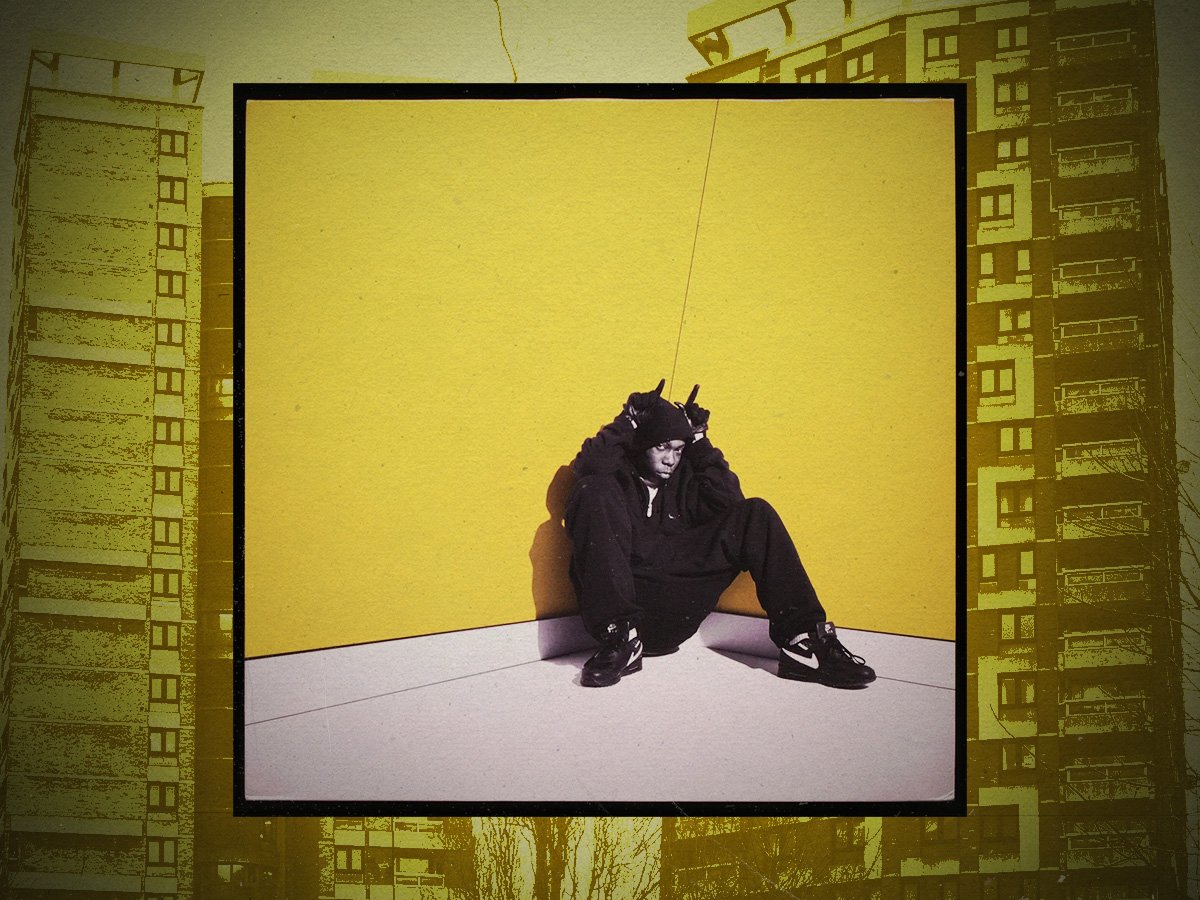

Walking through HMV, I saw signs for that year’s Mercury Prize-winning album Boy in da Corner, its vivid cover art lighting up the store. It showed Dizzee, in a black tracksuit and Nike Air Force 1s, sat in the corner of a bright yellow room, with his name and the album title in the upper left, written in stencil. I’d never heard of him, or the album, but if it was a Mercury winner, that was good enough for my 16-year-old brain.

This wasn’t the Dizzee we know now; this was years before the MBE, before he met Calvin Harris and went pop, and long before he was a near-permanent fixture on every festival lineup each summer.

Then I took that album home, put it into my Sony Discman and was transported to a city I’d visited many times, but this was different. This wasn’t the London I knew, but was East London, E3 to be precise, and a long way from the halls of the National History Museum or the turbine hall at the Tate Modern. It wasn’t the city my parents and school had taken me to, no, it was somewhere more urgent, more alive and more exciting.

Recorded between October 2001 and March 2003, the album had been released on XL just two months before its Mercury win and had been met with widespread critical acclaim as the vehicle that took grime from the underground into the mainstream consciousness. What that record did more than anything was take the listeners on a journey to Bow and show them how the community was living.

Growing up a country kid, I’d spent my time outside of school playing in fields and forests, a long way from the concrete tower blocks of East London, but this showed me a world I’d never seen first-hand, simmering in quiet rebellion. The album is so British, so uniquely London, that it couldn’t have been produced anywhere else, from the sound to the lyrics, invoking busy tubes, night buses and council blocks, filled with the energy of the British youth making sense of their environment.

(Credits: Far Out / Rob Oxley)

(Credits: Far Out / Rob Oxley)

Naturally, geography is key to the album, and Dizzee’s home of Bow perfectly encapsulates London as a whole, even if it’s in East London, as the theme of traditionally working-class areas dealing with gentrification is rife all over, with the neighbouring docklands being transformed into one of the world’s financial hubs. The shadows of skyscrapers loom over this record, from housing blocks to Canary Wharf, which, while it isn’t mentioned, feels very much part of the world the narrative is built on.

Grime itself was thoroughly London, birthed in the streets and forged in clashes, growing from the garage scene and taking influence from dancehall, jungle and rap. Easy to produce thanks to software like FruityLoops, it was recorded in bedrooms and small studios, before pirate radio spread it around the city. Grime’s signature at 140bpm translated the business of the streets and the buzz of the big city, all of which Boy in da Corner carried, but it also incorporated other aspects of British music, such as the near-choral refrain in ‘Jus’ a Rascal’.

I’ve always loved words for the power that they hold, and even at a young age, I was struck by the language in Boy in da Corner. I’d spoken English my whole life, but for 57 minutes, I found myself frequently having no idea what words meant. This was young London’s vernacular, that mix of East End slang and multicultural influence, such as patois. Even the pronunciation of words I knew was so different, shortened and emphasising different letters, and the dialect fascinated me, as anybody unfortunate to hear me say “wagwan” for months after can attest.

That East London dialect is across everything on the album, even including the title itself, Boy in da Corner, which Dizzee didn’t change to fit grammatical rules: he was true to himself, to East London, spelling the album in the way that he’d pronounce it.

The lyrics tell the story of what it was to be young, Black and British in East London in the early 2000s, living in a deprived area, just miles away from huge wealth and the money-making machine of Canary Wharf. It’s about living in inequality and making ends meet, and at times it’s even about romance, with ‘Jezebel’ and ‘I Luv U’ exploring dating culture and the gender dynamics of the time and area.

Where the album really shines is its description of urban isolation, which starts with the opener ‘Sittin’ Here’, where the with the lines “I’m just sittin’ here, I ain’t saying much, I just think”, Dizzee makes you feel like you’re there, taking you to those concrete stairwells, market stalls and the streets of E3.

Boy in da Corner introduced a generation to the sound of grime, showcasing East London and the lives of young Black Britons to the wider world. Dizzee opened the door so that Skepta and Stormzy could run through, creating something that perfectly encapsulated the streets that he grew up on, in the process, and encouraging others to talk of their experiences too.

Related Topics