Cyclists’ relationship with food and weight isn’t always a healthy one. In the search for peak power per kilogram, riders can tip from optimum output to heavy fatigue, illness and even disordered eating. Former pro Janez Brajkovič would routinely make himself sick after training, while Pauline Ferrand-Prévot’s Tour de France Femmes victory came via a drop of 4kg and accusations that she was ‘a bad example for young girls’ and warnings it set a dangerous precedent for the peloton.

There’s no suggestion that Ferrand-Prévot’s weight drop came at a physical and mental cost, but it did once again shine the spotlight on a sport where weight-related issues can be prevalent at both the elite and amateur level, especially relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs). Here we examine what REDs is, how cycling’s weight culture fuels it, how the problem can be addressed, plus how textbook learnings saw one rider nearly slip into the pink jersey…

Related questions you can explore with Ask Cyclist, our AI search engine. If you would like to ask your own question you just need to , or subscribe.

If you would like to ask your own question you just need to , or subscribe.

What is REDs?

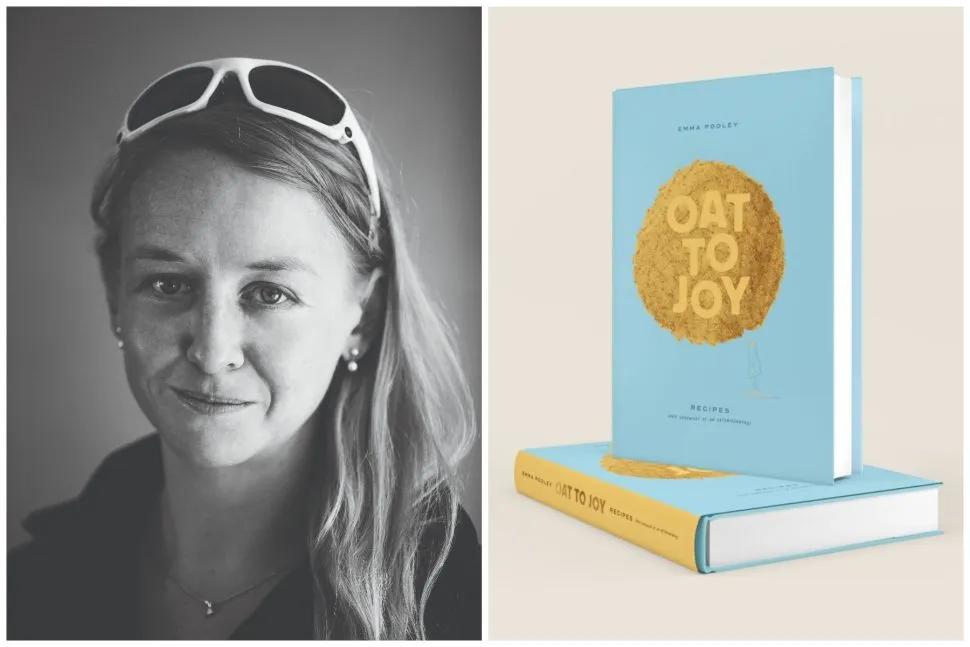

Former pro Emma Pooley says she had an eating disorder throughout her career and has just released the book Oat to Joy, which she described as a ‘long love letter to food, set in a culture where a lot of people seem to regard that as unprofessional or even shameful’. Juan Trujillo Andrades | Emma Pooley

Former pro Emma Pooley says she had an eating disorder throughout her career and has just released the book Oat to Joy, which she described as a ‘long love letter to food, set in a culture where a lot of people seem to regard that as unprofessional or even shameful’. Juan Trujillo Andrades | Emma Pooley

‘REDs impacts all bodily systems, leading to impaired physiological or psychological functioning,’ says Vanessa Zonas, head nutritionist at the team formerly known as Israel-Premier Tech.

‘It’s caused by problematic low energy availability, which is insufficient dietary energy intake for a period of time relative to the athlete’s exercise energy expenditure. It’s particularly relevant in professional cycling due to the extreme energy demands of training and racing at this level, plus the focus on weight, body composition and body position.’

According to a 2020 review of the literature, up to 58% of athletes are at risk of REDs, with a 2023 study finding that 65% of ultra athletes were at risk. Although this research focussed on females, males are commonly affected too.

REDs was introduced in 2014 by the International Olympic Committee, building on the concept of the female athlete triad, which comprised three interrelated health problems: low energy availability, menstrual dysfunction and low bone mineral density. A great driver of its evolution to REDs is that, aside from female-specific issues like menstruation problems, the symptoms and causes can inflict everyone regardless of gender, age and sport.

A combination of under-fuelling, overtraining and general stress can result in myriad issues that impact both performance – slower recovery, less power, lower endurance – and health – irritable, anxious, sick more often.

‘The ambiguity – maybe even conflict – between the pressure to maintain a certain body type in a sport like cycling and my love of good food is what motivated my book,’ says former professional rider Emma Pooley, who admitted to an eating disorder throughout her career. “At the very deepest level, [her new book] Oat to Joy is really a long love letter to food, set in a culture where a lot of people seem to regard that as unprofessional or even shameful.’

Pooley suggests cycling could learn from trail running, which she says has a far healthier culture around food, weight and performance, albeit does concede that at the elite cycling level, there ‘seems to be a greater priority these days on balancing performance and health. Ultimately, though, it’s still focussed too much on the performance aspect of food rather than the enjoyment, which I find quite sad. I guess professional sport isn’t about having fun, though the culture at an amateur level seems unhealthy too.’ A 2020 study by Cycling Weekly revealed that one in five amateur riders are putting their health at risk by under-fuelling.

Project REDs

EF star Cédrine Kerbaol run Instagram account @f.e.e.d_powr to raise awareness of REDs and more. Tim de Waele/Getty Images

EF star Cédrine Kerbaol run Instagram account @f.e.e.d_powr to raise awareness of REDs and more. Tim de Waele/Getty Images

It’s a stark but perhaps not surprising picture, and one that prompted former GB athlete Pippa Woolven to found Project REDs, an awareness and education initiative focused on REDs.

‘We provide free resources and toolkits to help athletes, coaches and support staff understand what REDs is, how to prevent it and how to support those affected,’ she says. ‘Our work spans schools, universities, clubs, and national governing bodies, with the goal of embedding better awareness and care around fuelling, recovery and athlete well-being.

‘I started Project REDs after personally experiencing the condition during my time as an international distance runner. I wanted to create something that I wish had existed when I was struggling: a trusted, practical source of information and support that bridges the gap between science and real-life sport.’

Project REDs includes practical resources to help the athlete understand, prevent and manage REDs to keep them healthy while delivering optimum performance. It’s a great, accessible resource but, according to a survey Project REDs undertook investigating elite athlete menstrual health, there’s still plenty to be done regarding educating athletes and their support teams.

‘From an injury and overall well-being perspective, athletes who experience menstrual irregularities are three times more likely to sustain a musculoskeletal injury than those reporting normal menses,’ said the study featuring input from 159 elite junior and senior athletes. ‘Further consequences can include decreased bone mineral density, leading to increased risk of stress fractures and osteoporosis. This is particularly concerning among young female athletes who form 60% to 80% of lifetime bone mass by age 18 and peak bone mass by 26 to 30.’

That’s of concern when there’s evidence that 45.9% of athletes have been told by a medical professional that it was normal to miss their period, have irregular menstrual cycles or start their period later in life because of their activity level.

‘There is a history of physicians prescribing hormonal birth control to induce bleeding in female athletes,’ says Zoras, ‘but we know that’s not the same as a naturally occurring period.’

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) both state that the first-line treatment for amenorrhea (absence of menstruation) in athletes is correcting low energy availability, not hormonal contraception.

The survey also revealed that 89% of the athletes had suffered with two or more REDs symptoms with 71% four or more. The most common symptoms were low mood, missed or irregular periods, preoccupation with food or weight, plus low iron, abnormal levels of fatigue, disordered eating, frequently ill or injured, low libido, performance drop and bone stress.

While many riders prefer anonymity, Unbound Gravel 2023 winner Carolin Schiff announced she’d sit out the remainder of the 2025 race season after a series of bone breaks over the past couple of seasons. ‘There is the topic of REDs hanging over me,’ Schiff posted on Instagram. ‘For quite a while, I haven’t had my period, so right now the most important thing is getting that back on track, taking this seriously, giving my body the rest and support it needs so that I can recover properly and hopefully come back stronger next year with a healthy body and stronger bones.’ Schiff also explained that her bone density ‘isn’t where it should be’.

French cyclist Cédrine Kerbaol, who holds a diploma in nutrition studies, also launched the Instagram account @f.e.e.d_powr to raise awareness of REDs.

Not solely a female concern

Harry Talbot

Harry Talbot

Though Zoras says that both the literature and the anecdotal suggest ‘the threshold of experiencing REDs symptoms in women is likely lower than males’ – in other words, it takes a lesser calorie deficit to experience these symptoms – research suggests male riders are nearly as vulnerable.

A 2019 study of 108 male recreational endurance athletes, including cyclists, who trained an average 12 hours each week, found that 47.2% were deemed ‘at risk’ of low energy availability, while only 19% of the cohort had no risk whatsoever.

One male rider who went public with his battle with REDs was American Jackson Long, who earned a place on the acclaimed University of Colorado cycling team. He dreamt of racing the Tour de France and tells his story on the Project REDs website.

That dream manifested itself in an increasingly singular and monk-like existence. It seemed the norm, he’d say later, in the ‘exercise addiction capital of the world’ in Boulder. His addiction saw him picked up by a top amateur team, where he spent the summer in relative solitude in a house tucked away in the hills of Arizona. Eat, sleep and train. And repeat. It’s an environment that lays the foundations for success but is one where small fissures can forge dangerously large cracks.

‘Looking back, that’s where the dark side started to emerge,’ he reveals to Project REDs. ‘I was working with a coach who I don’t think had any ill intent but just didn’t have any experience or training in nutrition, and was providing pretty poor guidance. Combine that with being isolated, living with just one person up in the hills for months, training for up to six hours a day and having no other social outlet. You kind of get fixated on certain things. That’s when I started to become hyper-fixated around food, weight and specifically carbohydrates.’

Like many athletes who struggle with REDs, carbohydrate and calorie restriction initially worked with personal-best climbs. But the wheels soon came off. Illness and fatigue enveloped him, he lost his sex drive (Project REDs say fewer than three erections each week for young male riders is a warning sign) and he was barely able to get out of bed.

Looking for answers, he had blood work, which revealed a number of biomarkers that were way off, including low vitamin B12, iron deficiency, a battered immune system and inflammation. A DEXA scan revealed shockingly low bone mineral density.

Long knew a radical change was needed. He abandoned ideas of becoming a professional and set about his recovery, which included a more ‘positive’ focus on nutrition. Interestingly, he turned to a plant-based diet that he recognised could also be seen as restrictive or even disordered, but, he says, it allowed him to eat enough carbohydrates.

‘I think there’s still a huge lack of awareness because it’s less apparent in males,’ he says. ‘There’s no menstrual cycle to lose.’

Long feels the culture is slowly changing, though remains concerned that many dysfunctional behaviours are engrained in male cycling, particularly around carbohydrate restriction and weight gain. He is now a nutritionist.

Guidance from up high

Former World Champion Grace Brown now heads up the Cyclists’ Alliance, which is campaigning for mandatory REDs screenings. Alex Whitehead/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

Former World Champion Grace Brown now heads up the Cyclists’ Alliance, which is campaigning for mandatory REDs screenings. Alex Whitehead/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

The UCI is now under pressure to formalise how teams should prevent and react to REDs. A press release in late September stated that the ‘UCI is in the process of finalising documentation and tools that can be used by team doctors to enable the diagnosis of REDs. The strategy is to rely on a screening and risk-assessment tool validated and published by an International Olympic Committee consensus group. The adapted tool provided by the UCI includes questionnaires tailored to competitive cycling and a risk assessment that is easy for team doctors to use’.

The UCI added that they’d approved a new weigh-in protocol for athletes competing in UCI-sanctioned e-sports events where riders compete in person, like the UCI Esports World Championships. ‘The objective is to eliminate dangerous weight-cutting using voluntary dehydration, as well as to promote fair competition. It’s part of a longer-term vision to safeguard athlete wellbeing in this relatively new and fast-growing cycling discipline.’

Pressure on the international governing body is coming from several quarters including the Cyclists’ Alliance, the de facto representative for women in professional cycling since its formation in 2017. In November 2024, the Alliance put forward a proposal to the UCI to encourage the mandatory screening of REDs including measuring bone mineral density.

‘The current system is not set up to protect female health,’ Cyclists’ Alliance President Grace Brown said in a statement, ‘so I believe it’s our duty to continue educating and advocating for better standards that allow women to perform with well-fuelled, strong and happy bodies.’ It’s an important step forward for female riders and teams that are traditionally under-resourced.

Assessing for REDs

On the men’s side, there are fewer financial concerns, meaning they have easier means to assess for REDs, if that fits within the culture of the team. Zoras use the REDs clinical assessment tool that takes into account myriad physiological and psychological factors including low blood glucose levels, sleep disturbances and body dysmorphia.

Zoras measures bone density via DEXA scans. Low bone mineral density is a problem at the elite level with traumatic fractures from crashing the number one reason for withdrawing from the Tour de France between 2010 and 2017. ‘Of course, it’s challenging to prove that low bone mineral density leads to more frequent traumatic fractures in cyclists, but it’s a likely conclusion that weaker bones would be more likely to break on impact,’ she says.

Her team undertake bloodwork to assess for REDs red lights such as low testosterone and triiodothyronine (T3), which is the active form of the thyroid hormone that’s responsible for many functions including regulating metabolism and energy use. Plus, she employs questionaries to better understand a rider’s relationship with food and body image.

‘There is concern if there are periods of long fasting; if a rider has a very real fear of weight gain; feelings of guilt after eating; feelings of being out of control around food; binging or purging. Purging could be vomiting, but it could also be adding additional hours to training as a result of feeling like they overate or equating emptiness with success.’

All of this is important for regular assessments that the riders are keeping healthy. That is, of course, great for the individual and fiscally beneficial for the team. Key to preventing disorders like REDs, Zoras says, is creating an environment whereby riders feel safe in relaying to the team if they have concerns: ‘Communication and self-reflection are vital in decreasing potentially harmful behaviours, as is how we all behave. We focus on avoiding appearance-based comments – positive and negative – and instead appropriately discuss body composition and weight metrics in the context of performance.’

Periodisation of nutrition

Derek Gee’s breakthrough 2025 season came with help of a monitored programme that enabled him to lose weight without losing power. Tim de Waele/Getty Images

Derek Gee’s breakthrough 2025 season came with help of a monitored programme that enabled him to lose weight without losing power. Tim de Waele/Getty Images

Successfully walking the tightrope between fuelling, weight management and peak performance is no easy task when wasted calories and ounces can be the difference between victory or success, a lavish lifestyle or desperately seeking a new contract. But when a rider and team hits the nutritional sweetspot, the results can be impressive.

‘In April 2024, we started a GC project with an athlete who began that period weighing 76kg after a period of injury.’ Zoras doesn’t name the athlete in question but as her story continues it becomes clear it’s Canadian Derek Gee.

Gee crashed at Omloop Het Nieuwsblad and was out for six weeks with a fractured collarbone and concussion. ‘Because of that, he naturally dropped in weight on full return to training, followed by a further decrease in weight to 72kg from a pre-Dauphine altitude camp,’ Zoras says.

Gee took a stage win at the Dauphine followed by ninth on GC at the Tour de France at a race weight of 73kg. Into the off-season he nestled around 74.5kg. ‘Because he started lower than our 76kg starting point, we had less work to do at the beginning of the 2025 season.’

After altitude camps in February and April, Gee lined up at the Giro d’Italia around 70.5kg – around 2.5kg lighter than the 2024 Tour. Importantly from a performance perspective, his average 20-minute power at both Grand Tours remained the same (around 442 watts) despite the drop in weight. In short, Gee and his team had safely forged a rider with a higher power-to-weight ratio. The result? The team and Gee’s highest Grand Tour GC finish of fourth overall.

‘All in all, we saw a pretty significant shift in his weight, while avoiding problematic low energy variability,’ says Zoras.

Key for Zoras was that Gee, a rider in his late 20s, was more mentally and physically resilient than some riding cohorts, especially younger athletes, plus he had no existing medical issues. As for the key strategies to safely shed pounds without leaching watts…

‘When it came to nutrition management, often when an athlete goes into energy deficit, it’s typically to the detriment of carbohydrate. So we’d ensure that the focus was around sufficient carbohydrate availability pre-, during and post-rides to protect the quality of that training, pulling back when it’s not critical. We used a moderate calorie deficit and it was periodised around the race calendar. So, as we approached races, we stopped the deficit and ensured that he was well-fuelled.’

They also ensured Gee grazed instead of gorging. ‘We know that even if an athlete eats enough energy throughout the entire day but it’s mistimed – in other words, they’re not fuelling enough around or during training – even if they eat enough and compensate via a larger dinner, that can actually be a risk factor for experiencing some of these symptoms of low energy availability.’

Zoras also began tracking Gee on a daily basis, which might sound counterintuitive to forging a mindset that doesn’t obsess over food. ‘More data can actually be less overwhelming. He’d only ever tracked intermittently, so if he saw a high number, he’d be like, ‘”Oh my God.” And if he saw a low number, he’d be like, “Yes.” Daily tracking actually removed the emotion and helps the rider understand daily fluctuations happen, so actually decreased the stress around that metric.’ Gee and the team worked in harmony for a safe and positive outcome.

At the top end, cycling’s enduring pursuit of marginal gains has forever ridden a fine line between discipline and danger. Weight, once viewed purely as a performance metric, is now recognised as a health marker that can determine both the length and quality of a rider’s career. As nutritionists, coaches and governing bodies finally confront REDs, the challenge ahead is cultural as much as scientific, creating an environment where strength, fuelling and well-being matter as much as speed. Will that happen? Arguably it is, though it’d be naïve to think the mantra that lighter is always better will simply float away, especially if a rider or team is desperate for results.

As for what you, the recreational rider, can take away if you’re concerned about your own situation, we’ll leave that to Project REDs founder Woolven, who says you should fuel before, during and after training – don’t wait until after sessions to eat; avoid fasted rides, especially long or intense ones; include carbohydrates in every meal and snack; and monitor recovery and mood as much as training data – persistent fatigue, poor sleep, irritability or disrupted hormones are warning signs.

‘Ultimately health and performance go hand in hand, and the most successful athletes are those who fuel properly, rest well and think long-term,’ she says. ‘You don’t need to take shortcuts with nutrition or training to perform at your best. Sustainable performance is what keeps you progressing, enjoying your sport and staying healthy.’