No tour of a modern art gallery is complete without the caustic refrain: “A child could have done that.” In the case of Jackson Pollock, father of the drip painting, a study suggests the sceptics may have a point. Children can indeed produce something similar to his work. Oddly, though, most adults cannot.

Pollock, an American painter of the abstract expressionist school, became famous in the late 1940s for placing his canvases on the floor and flinging, dripping and pouring paint across them.

Fans saw genius in his looping skeins of colour; detractors saw chaos. Pollock argued for something different: his paintings were the product of controlled movements, shaped by the way his body shifted as he worked.

• ‘Hidden images’ in Pollock’s paintings may have been intentional

That idea — that the mechanics and balance of his body determined the look of the art — is now the focus of a study published in the journal Frontiers in Physics.

Richard Taylor, who is a physicist, a psychologist and an artist at the University of Oregon, supervised a team that recruited 18 children aged four to six, as well as 34 adults aged 18 to 25, to create their own Pollock-inspired pictures. They were asked to splatter paint on paper laid on the floor, producing what the researchers called “pour-paintings”.

The resulting artworks were subjected to fractal and lacunarity analyses, mathematical techniques that quantified, or scored, the complexity of the patterns and the blank spaces between the streaks of paint.

The results revealed that the adults tended to make denser patterns that darted in many directions. Children, by contrast, produced lighter, simpler trails of paint with more empty space between them. They changed direction less often — not because they lacked energy, but because their bodies moved differently.

The analysis also found that the children’s pictures were closer to Pollock’s own artworks.

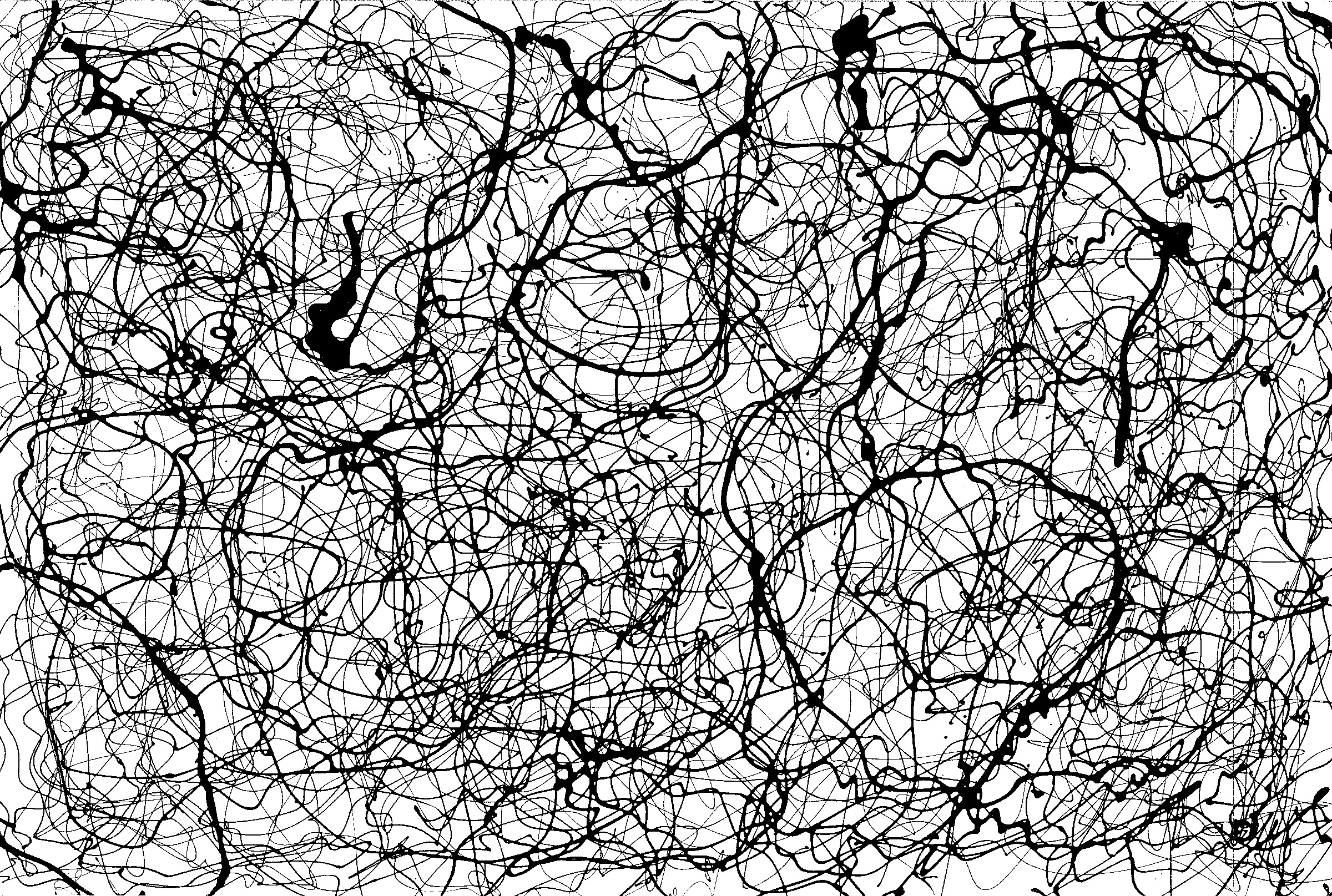

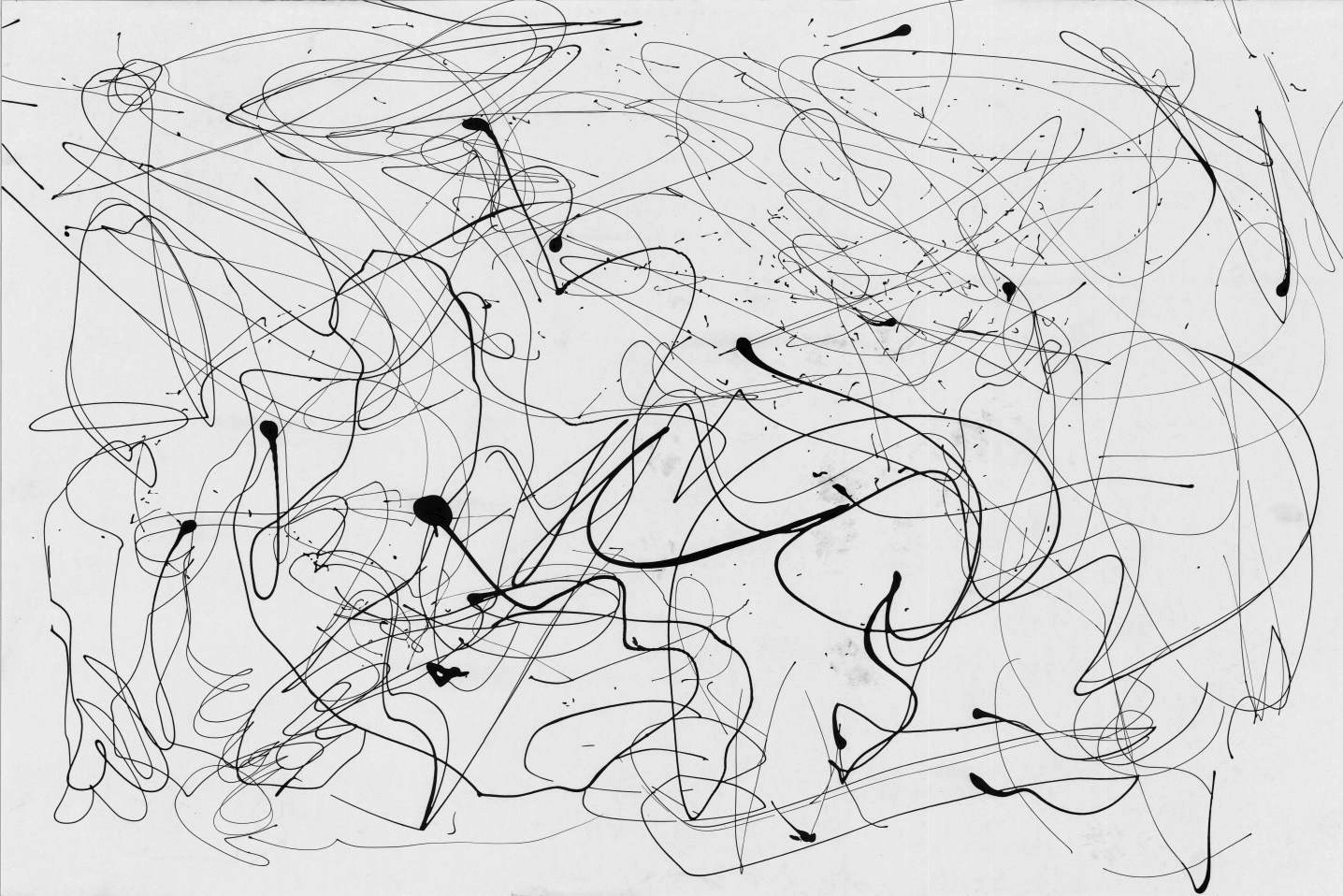

A dense pattern created by an adult and, below, a more open artwork by a child

“Remarkably, our findings suggest that children’s paintings bear a closer resemblance to Pollock paintings than those created by adults,” Taylor said.

The explanation may lie in how Pollock experienced problems with his sense of balance. Francis O’Connor, the late Pollock scholar, has argued that after being almost strangled at birth by his umbilical cord, the artist experienced a “loss of manual dexterity [that was] decisive in his art”.

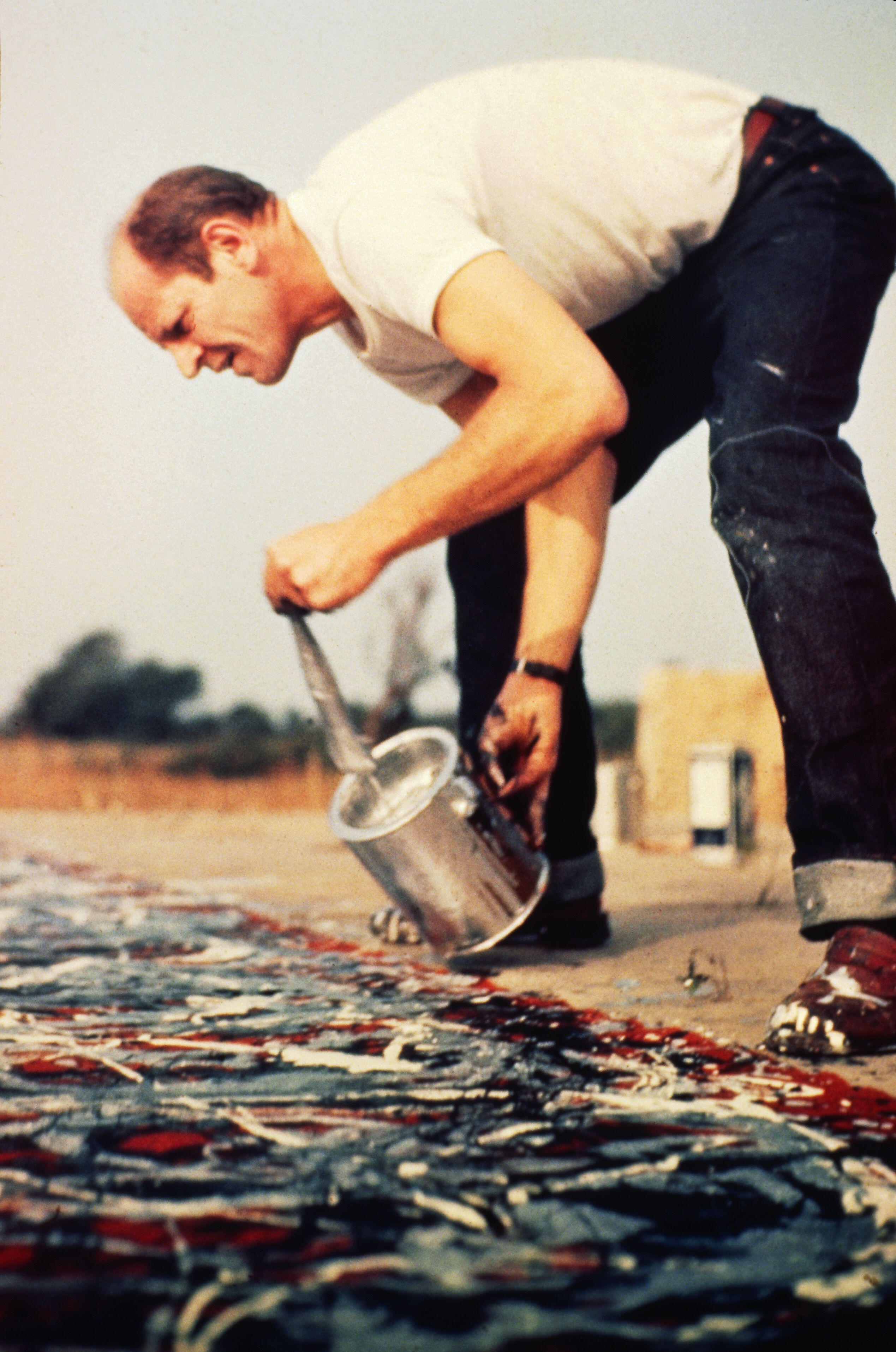

Pollock’s impaired balance affected the way he was able to pour paint on the canvas

ALAMY

The authors of the new study suggest his movements were therefore less elaborate than those of a typical adult, making his paint trails more childlike.

• Pollock and Putin, peas in a culture war pod

The researchers also looked at how people reacted to the paintings produced by their volunteers. When viewers judged them, they preferred the simpler, more open patterns — the kind that appeared more often in the children’s work.

Taylor suggests we may be drawn to such patterns because they echo those found in nature, which our brains find easy and calming to process. Drip paintings, sometimes written off as childish, may have therapeutic value.

The study does not claim that children can match Pollock’s intentions or artistic importance. It only suggests that the physics of their movements brings them closer to his style than better-balanced adults. The authors note that art history is full of cases where physical and psychological conditions shaped great work: Claude Monet’s cataracts, Vincent van Gogh’s mental turmoil, Willem de Kooning’s Alzheimer’s. Pollock’s unsteady balance may, it seems, belong in the same company.