London is famed for many things, but American football is not one of them. Yet, in the south of the capital, there is a team making a big impact in what is a minority sport in England.

The London Warriors have won seven national titles, known as BritBowls, the most of any British team, and over the past two decades have become a phenomenal breeding ground for talent, with players and coaches going on to be involved in the game in the United States, and two former players even making it to the NFL, such as Efe Obada.

But stardom and the spotlight are not the aim. “We try to keep to that core of what we are trying to do, which is helping kids from bad situations,” general manager Simon Buckett tells The Athletic.

Run as a charity, the south London club started as a junior team in 2005. It now has a men’s and women’s senior team, as well as youth teams for ages 7 through 19.

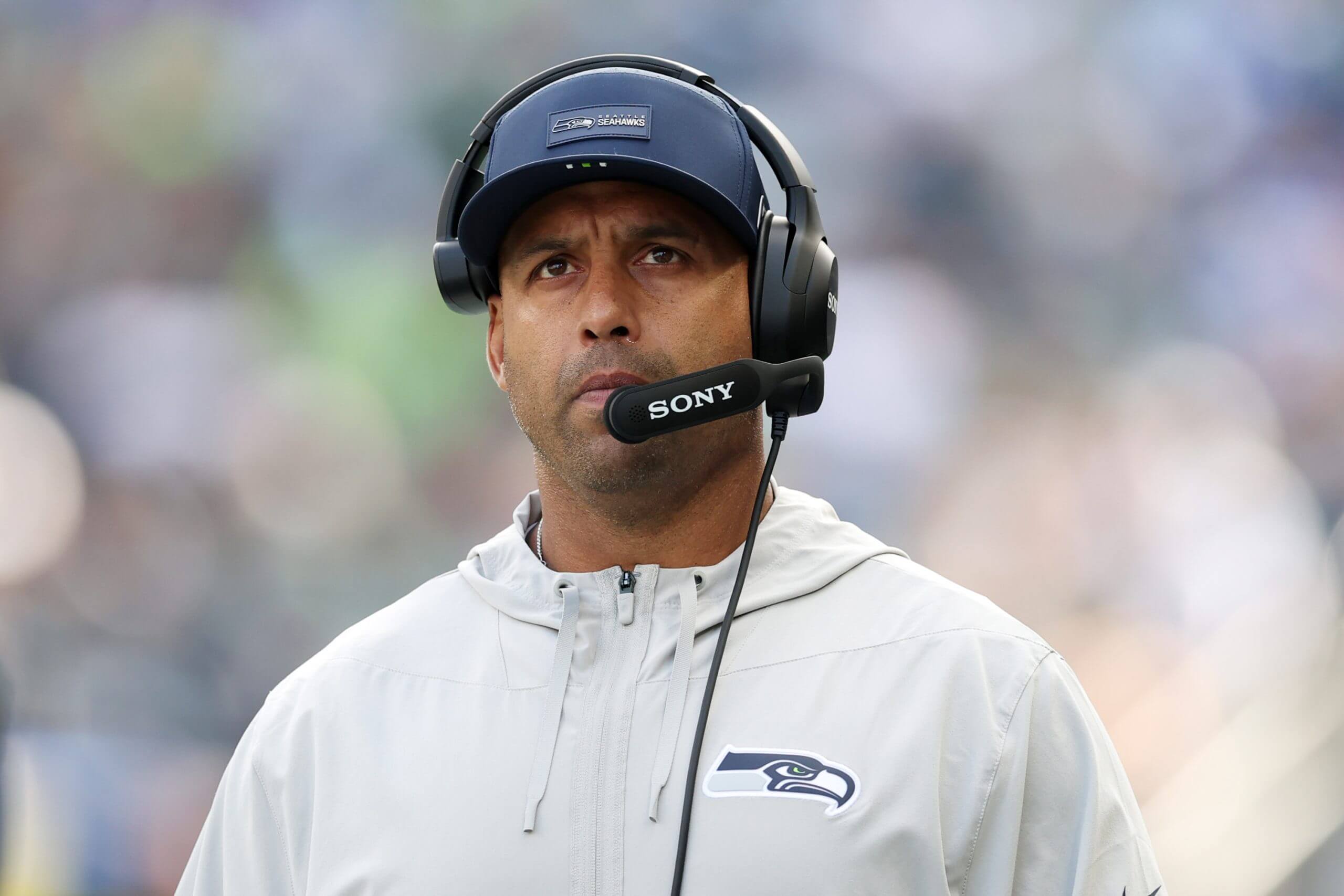

Speaking to Warriors former coach Aden Durde, now the Seattle Seahawks’ defensive coordinator, and former players, such as TV and radio presenter Vernon Kay, The Athletic discovered a club that is at the heart of the game’s grassroots in the United Kingdom, an amateur team aiming to achieve “professional standards.”

The first British NFL coach: ‘I was helping them grow up’

Durde, the first British-born coordinator in the NFL, began his coaching career at the London Warriors in 2011.

“A lot of the things I used at the Warriors to coach players, I still use now. To me, there’s not a lot of difference,” Durde says. “Football-wise, there’s a huge difference. It’s literally like night and day. But the person and the people that you’re coaching and their needs and how you connect with them, they’re really the same thing.

“The special things are the same when you have a really good team at any level. It was the connection, it was the brotherhood, it was the commitment from the players and the coaches to do something that a lot of people didn’t believe they could do.”

It was current Warriors head coach Tony Allen who persuaded him to begin a coaching career, Durde says. “After two years, I committed and said, ‘Yeah, I’ll coach the linebackers here.’ That was when it started.”

As is the case with all of the Warriors, Durde volunteered while balancing other work commitments and coached the team on weekends.

Defensive coordinator Aden Durde started his coaching career at the London Warriors. (Steph Chambers / Getty Images)

“At the Warriors, you’ve got kids that didn’t even know what American football was. They were financially limited in a lot of areas of their lives, and you had to convince them to create a lot more structure in their life, to pay for things and to be responsible and to do these things,” he remembers.

“Flip it forward to the NFL. You’ve got a lot of business and contracts and money that overarch a lot of people’s decisions. And you have to cut through that to get people to commit and connect. And at times, put some of those things aside for the greater good, and at times make those things the forefront.

“A lot of the special traits were just like a good group of people trying to commit and do something that they wanted to do. That’s what was special about the Warriors.”

The 46-year-old was a linebacker in the now-defunct NFL Europe and made the practice squads of the Carolina Panthers and Kansas City Chiefs in the 2000s. Coaching, he says, helped “keep me connected to the game.”

“And I loved the kids,” he adds. “I was kind of like helping them grow up. When you play, it’s that excitement when you’re getting ready to play, that part of the game — that’s addictive. And when it stops, it’s like, ‘Wow.’

“And then when you coach, suddenly you help, you give someone some information and they do it, and they are better. That is kind of like, ‘Wow, that’s pretty cool.’”

The celebrity co-sign: ‘The Warriors changed my life’

Vernon Kay, a recognizable face on British television over the past two decades, became hooked on American football after watching the hits of Ronnie Lott on free-to-air Channel 4 in the 1980s.

He began playing at 13 and continued throughout his teens. At 36, fate reintroduced him to the game — and all but one of his former Manchester All Stars team-mates — when he made a one-off documentary for British terrestrial channel ITV in 2010.

Again, Allen, the first head coach of the NFL Academy, had a telling influence.

“I still loved the contact, I love the physicality of American football, I play free safety, and I love it,” Kay says. “Tony Allen said, ‘Look, if you still like playing, come and keep your toe in with the Warriors.’ I went down, did a couple of training sessions, and absolutely loved it.

“I got stuck in and played for four years. The first two years, we lost in the final. The second two years, we won back-to-back BritBowls.

“I got addicted to actually learning American football — learning about scheming and defense. We weren’t playing it. We were in it. We were all invested, and that’s why I absolutely loved the Warriors to bits.”

Presenter Vernon Kay hugs Menelik Watson following an NFL game between the Raiders and the Dolphins at Wembley Stadium in 2014. (Ben Hoskins / Getty Images)

The BBC Radio 2 host is still in regular contact with many of his former teammates. “I realised that you can take a lot of kids from different backgrounds, different upbringings. We had the whole spectrum of young men and we were all playing on the same team. It didn’t matter where you were from or who you were; everyone was equal. I have nothing but high praise. I always say to Tony that being in the Warriors changed my life,” he adds.

“Tony Allen doesn’t like using the phrase ‘amateur team.’ He doesn’t like using ‘Sunday league football team.’ Tony wants to achieve professional standards and professional levels. He says, ‘We play part-time football to a professional standard.’

“At practice, his mentality is everything that you would experience in the NFL. You turn up on time, you get your s— done, you do it to the best of your ability, and I’ll see you at the next training session. It’s very, very rare that any one of the Warriors gets a pat on the back from Tony Allen.”

The special talents: ‘It made me believe I could make a career out of this’

Temple University is in the heart of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Londoner Peter Clarke, now a junior for the Temple Owls, swapped pie and mash for cheesesteaks in 2023. The tight end caught two touchdowns for the Division I college last year.

He was first introduced to American football through flag football, brought to his school by the Jacksonville Jaguars. He was referred to the Warriors, where he went through the youth system before joining the NFL Academy in Loughborough, England, then progressing to Temple.

“The London Warriors took my flag understanding, my initial love and fun for the game and made me believe I could make a career out of this, go to university or to a different country and play, and make money from the game,” he told The Athletic in May.

Peter Clarke reacts after catching a touchdown against the UTSA Roadrunners in 2023. (Mitchell Leff / Getty Images)

According to the Warriors website, over 20 youth players have made it into the NFL Academy, more than 24 former Warriors have played professionally in Europe and Canada, and over 25 have played at American high schools and colleges.

Other former Warriors Division I talents include 23-year-old Mississippi State tight end Seydou Traore, who was featured on the college football Netflix documentary “SEC Football: Any Given Saturday,” and Sam Fenton, the first British quarterback to go to a Division I college. The 21-year-old Fenton is a freshman at the University of South Florida.

Many in the academy look up to Obada, who played 80 games in the NFL between 2018 and 2024 for the Carolina Panthers, Buffalo Bills and Washington Commanders.

The 32-year-old defensive end was born in Nigeria but was trafficked to London and put into foster care. He was 22 and working as a security guard when he discovered the Warriors.

He would later join the NFL’s International Player Pathway (IPP) and became the first IPP player to make a 53-man roster, doing so with the Carolina Panthers in 2018.

Obada’s inspiring story exemplifies how the Warriors have helped their community. In an interview with The Athletic in 2019, Obada said the Warriors saved his life. He is now helping the next generation and, earlier this month in London, he received the Prince Philip Award for outstanding contributions to youth work.

The community: ‘It completely and utterly shaped who I am’

Kevin Keohane played for the Warriors for six years until he was 37, winning four BritBowls.

Kevin Keohane wears one of his BritBowl rings (right) and a British American football hall of fame ring (left). (Eduardo Tansley / The Athletic)

He remains involved in the game as the assistant head coach and offensive line coach for the Great British national team on a part-time basis, fitting it in alongside his full-time corporate job. That makes him one of over 95 players and coaches to have represented Great Britain from the Warriors.

“My partner plays American football, I met her through the sport,” Keohane says while watching the Warriors compete at BritBowl XXXVI in September at the Butts Park Arena, Coventry — the team’s sixth straight appearance in the season finale. “I’d probably say American football has given me more than I could even comprehend in terms of my life experiences. This sport has completely and utterly shaped who I am as a person.”

He describes the Warriors as “brothers in arms” who teach you to become better in every aspect of life. Keohane would train in the gym for an hour three to four times a week and attend two practices in the preseason or one practice and a game in-season while part of the Warriors.

“You have to get along with people from all walks of life. It’s such a multicultural place that brings people together. This is one of the few sports that really does that when you look at the demographic of players,” Keohane says.

The Warriors’ women’s team in action during training. (Olamide Photos)

Buckett, the general manager who has been involved in the club for 18 years, says: “Every time there’s a new team, whether it’s the under-14s all the way through to the adults, there’s always something you can learn from somebody because everyone comes from such a different background.”

In his 18 years at the club, Buckett has seen children escape gangs and various tough situations after finding a safe space at the Warriors.

“My fondest memories are when you see a kid that’s on the field playing that came from nothing, or came from a real bad situation. The most famous one is probably Efe, but there are dozens and dozens of kids that you don’t know because they’re working in the city or working somewhere that’s not the NFL, but without the Warriors, they wouldn’t have been where they are today,” Buckett says.