ANALYSIS

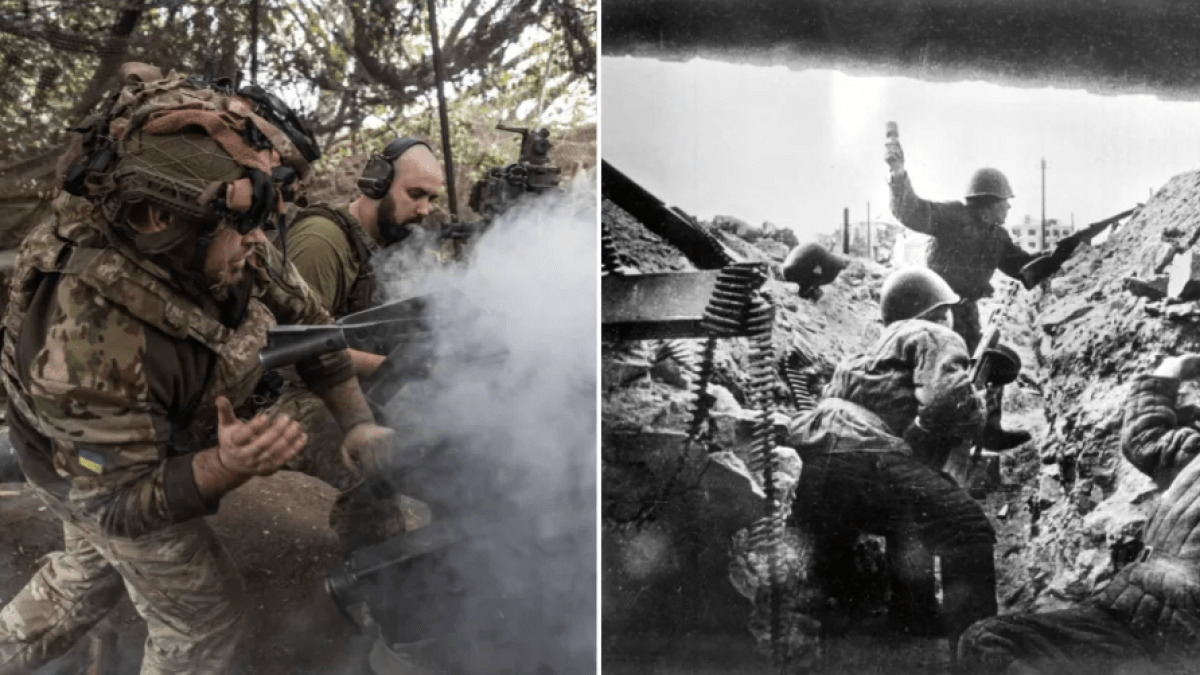

The brutal fight for Pokrovsk is bringing strong flashbacks to the battle for Stalingrad in the Second World War

The small eastern steel town of Pokrovsk – with a pre-war population of 60,000 – has been one of the swing battlegrounds of the war in Ukraine. It has been under siege for nearly a year and a half and still hasn’t completely fallen to Russian forces.

Casualties on both sides are now in the tens of thousands. Russian infantry travelling by SUVs and even motorbikes have been caught frequently in open ground by Ukraine’s artillery and drone bombardment.

Russian President Vladimir Putin wants the town and its neighbour, Kupiansk, seized so he can declare a major win by the end of November, which would mean next week.

Putin is also pushing for the surrender of Pokrovsk and nearby cities by other means, working his back channels with US President Donald Trump and his envoy Steve Witkoff to get Ukraine to give them up as part of a peace deal.

The battle for Stalingrad was arguably the swing battle of the Second World War, at least in Europe. Its scale – both in terms of numbers involved and strategic significance – dwarfs the battle for Pokrovsk. Yet, it lasted a third of the time Russia has struggled to take Pokrovsk.

The battle for Stalingrad ended with German forces surrendering – some 91,000 soldiers, including 24 generals.

The commander of the Red Army from within “the cauldron” in the heart of Stalingrad was General Vasily Chuikov. He proved a master of modern urban warfare, and his innovations have lessons for those fighting in Pokrovsk and other towns and villages.

The Battle of Stalingrad, November 1942 (Photo: Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty)

The Battle of Stalingrad, November 1942 (Photo: Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty)

They also have a warning for the next phase of the war in Europe, which Russian command now seems to be planning for.

Urban warfare – the battles for Stalingrad and Pokrovsk – are deadly games of hide-and-seek among the ruins and rubble of buildings, burned-out tanks and artillery pieces, as well as in basements and cellars. Tanks are of limited value – they are easily immobilised and become barricades for defenders.

Chuikov himself invented a tactic of “hugging the enemy”. Russian infantry squads closed with the German defenders so they could not be covered by artillery support and dive bombers from the air, for fear of killing German forces.

In Ukraine, drones have dominated the air, and in open ground, infantry and artillery are quickly spotted. “They found they only had a minute or two to move or take cover, once sighted,” a British military observer said of the Donbas battlefront.

This has led to a technology race – as both Russia and Ukraine have innovated with new types of drone, electronic warfare and radiation weapons. This is happening at an alarming rate, which far outstrips similar developments in most Nato forces, including the UK.

But, in close urban fighting drones cannot dominate, as fighters use rubble and ruins and wrecked vehicles for cover. Artillery and missiles are also not very effective.

Vladimir Putin at a wreath-laying ceremony in the Hall of Military Glory in Volgograd, formerly Stalingrad, on 29 April, 2025 (Photo: Alexander Nemenov/AFP)

Vladimir Putin at a wreath-laying ceremony in the Hall of Military Glory in Volgograd, formerly Stalingrad, on 29 April, 2025 (Photo: Alexander Nemenov/AFP)

“Nothing can take the place of small groups of infantry,” wrote Chuikov of Stalingrad. “I don’t mean barricades street fighting – there was little of that – but groups converting every building into a fortress and fighting for it, floor by floor and room by room.”

British forces had to learn anew about fighting in built-up areas in the decades-long campaign in Northern Ireland. Israeli forces in Gaza have faced the same problem – to penetrate the rubble and the labyrinth of tunnels and bunkers that allowed Hamas to keep a fighting force, albeit only about 15,000 men, despite two years of bombardment that turned much of Gaza above ground into a moonscape.

Drones and electronic warfare have been hailed as the new element in the Ukraine war.

Drones by the million are pervasive – so much so that every platoon and company commander “can command his own bespoke drone air force”, in the words of one British commander.

Drones has become a key feature in the war in Ukraine (Photo: Viacheslav Madiievskyi/Ukrinform/NurPhoto via Getty)

Drones has become a key feature in the war in Ukraine (Photo: Viacheslav Madiievskyi/Ukrinform/NurPhoto via Getty)

The drone hybrid battle concept has superseded the standard Nato doctrine of Land Air 2000 – which was essentially a refinement of the German Blitzkrieg tactic: fast-moving units of infantry and armour supported by air forces, missiles and attack helicopters hitting enemy lines and positions in depth.

This was the essence of the “shock and awe” tactics of the US in Iraq and Kuwait in 1991.

This year, heavy rain and clouds have swept the battlegrounds of Donetsk, severely hampering the flight of drones – they don’t work well in rain. Meanwhile, Russians have been moving round Pokrovsk with small squads of infantry – perhaps beginning a Stalingrad learning curve. Ukraine now doesn’t have sufficient infantry to oppose them.

For the UK, the lessons of Pokrovsk and the likes mean we need to go back to the future.

Our approach to defence, security and resilience needs to be more urgent and agile. Most of the innovations in June’s strategic defence review won’t happen for another three years at least. New techniques brought by cyber, AI, and drones must be embraced with critical examination, as much as enthusiasm for a new craze.

The way wars are fought today, in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan, requires fighters on the ground – the equivalent of the Poor Bloody Infantry of the First World War – to take and hold ground.

The news out of Pokrovsk and eastern Ukraine should put us on notice – as should the attempt by Russia to get Ukraine to surrender key cities via a Trump-backed peace plan.

Ukraine’s European allies fear Russia is setting up for a wider confrontation – something No 10 and Whitehall doesn’t want to hear, and which Europe isn’t ready for. Adaption and speed to innovate will be key. Those are the lessons we should be learning from both Stalingrad and Pokrovsk.