In March, John Springford (Deputy Director of the Centre for European Reform) wrote a response to my Policy Exchange paper (Less than meets the eye), which examined five flaws in contemporary trade analysis. In his critique, Springford defended the integrity of his doppelganger approach, which shows UK exports underperforming since Brexit.

Springford’s doppelganger matters. It was widely credited in the UK and Europe as a reliable guide to the impact of Brexit on UK trade. Springford is often quoted on the topic, including in the Financial Times. And he continues to support pre-Brexit forecasts that Brexit would reduce UK trade by 15%.

And yet Springford’s analysis contains grave errors and misinterpretations. The result is to obscure the real reasons behind the UK’s poor trade performance.

1. Aerospace is key to post-Brexit UK trade problems

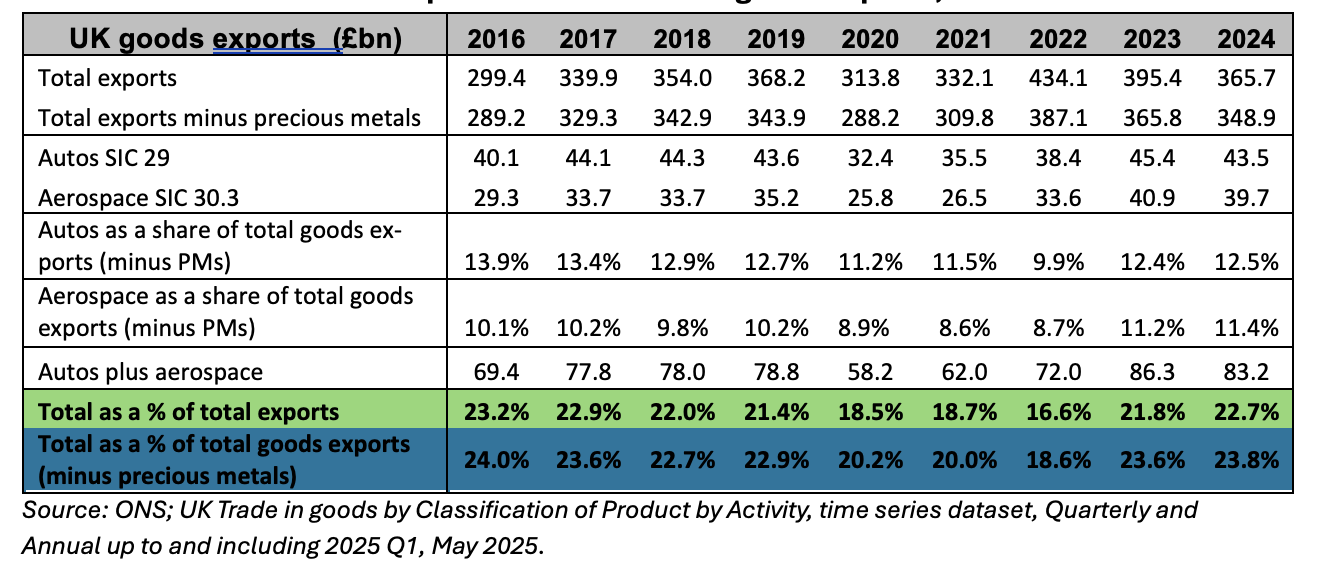

An appreciation of UK aerospace is essential to a proper appraisal of post-Brexit trade. According to ONS data it is the UK’s second largest export industry (see Table 1). Include Rolls-Royce services contracts (which generate more than 60% of its commercial engine sales) and aerospace already vies for the top spot in UK goods exports.

The starting point for any post-Brexit trade analysis should be that aerospace delivered the most severe falls in exports. In 2020 and 2021, exports dropped £9–10 billion on 2019 levels.[i] In percentage terms, this surpassed even the auto sector’s downturn. In addition, aerospace-related services exports appear to have fallen by around £2.4 billion.[ii]

But the cause of this collapse has nothing to do with Brexit. It was the pandemic-related collapse in commercial aerospace. Airliner deliveries from Boeing/Airbus halved from 2018 to 2020, from 1,606 to just 723[iii]. And that duopoly is where the bulk of UK civil aerospace exports end up. Recovery has been slow.

The problem – for economic modelers – is how to incorporate this sectoral hit into a doppelganger cohort. Very few countries have a commercial aerospace sector to rival the UK’s.[iv] And just to add complexity, our exports are skewed towards wide-body aircraft, which were particularly impacted. Airbus deliveries of the A350 and A330neo in 2024 were still around half what they had been in 2019.[v] And so the aerospace nosedive hit UK exports hard and asymmetrically.

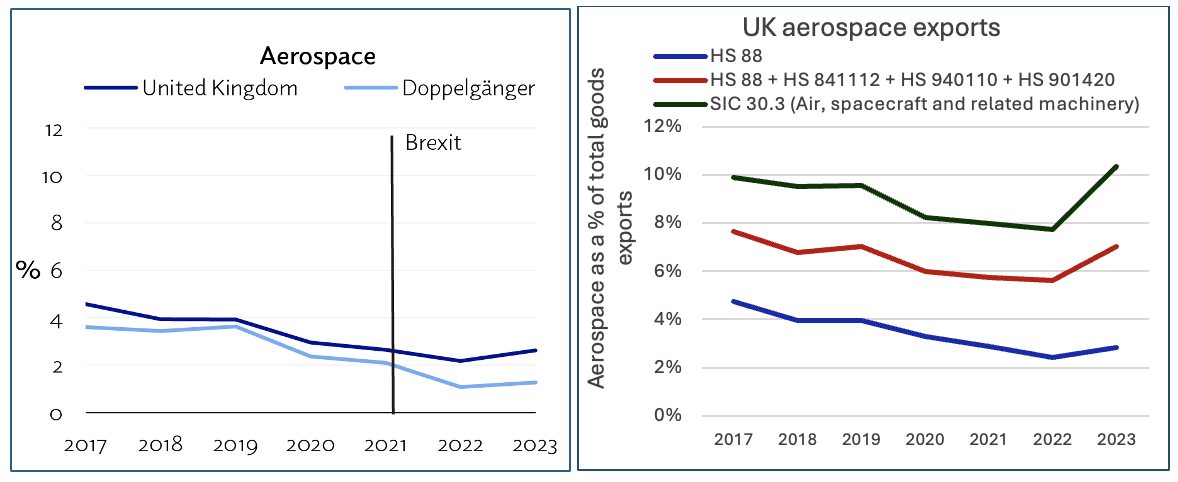

Figure 1: UK aerospace exports as a percentage of total goods exports.

Source: (left) Springford, Policy Exchange’s partial analysis of the impact of Brexit on trade “UN Comtrade, export values HS Chapters … 88 as a share of total goods exports.” (right) Exports as a share of total goods exports: HS 88 (July 2025) plus HS 88 plus 841112 (turbojets); HS 940110 (avionics); HS 901420 (aircraft seating). UN Comtrade, July 2025. Also SIC 30.3. Source: ONS: Trade in goods by Classification of Product by Activity, time series dataset, Quarterly and Annual up to and including 2025 Q1. May 2025

At first sight, Springford appeared to do this well in his response. His aerospace chart (reproduced above left) shows aerospace delivering a rapidly declining share of UK goods exports from 2019 onwards. And the UK’s performance tracks his doppelganger. But something is wrong. His UK data begins in 2017 with aerospace accounting for just 5% of UK goods exports. It should be 10% (see Table 1).

The problem is that most UK aerospace exports fall outside the HS 88 chapter that Springford used to analyse aerospace. Missing are some of the UK’s most valuable engineering exports, including Rolls Royce jet engines (HS 841112), navigational avionics (HS 901420) and aircraft seating (HS 940110) (see red line, above right).

Add together all the thousands of parts that UK companies sell into the global aerospace industry (the green line) and they comprise a far, far higher share of UK exports than Springford’s doppelganger (10% of UK goods exports in 2023, versus just over 1% for the doppelganger).

What this means, in turn, is that Springford’s doppelganger cohort does not remotely incorporate what turned out to be the biggest sectoral ‘hit’ to exports in the post-Brexit period.[vi] As a result, the UK is bound to underperform the doppelganger cohort, purely because aerospace is one the UK’s two biggest goods-export industries.

2. Energy silently skews the Springford doppelganger

Secondly, just because UK exports have diverged from other countries since 2020, it doesn’t automatically mean Brexit is the cause.

Consider the role of energy. In his critique, Springford revealed the basic composition of his doppelganger. He gave Norway pole position with a 23% share, and the US second place with a 19% share. Both countries are huge energy producers, and both have enjoyed a post-2016 export boom in energy.

Meanwhile, the UK is on a whole different trajectory because Government policy has encouraged the gradual closure of domestic oil and gas production. The divergence is startling, and yet it rarely figures in Brexit-related economic commentary:

- Norwegian gas production hit a record high in 2024.[vii] Total Norwegian hydrocarbon production is steady, and still not far short of its 2000s peak.[viii] Oil production is falling, but not nearly so fast as in the UK.

- The US has achieved records in domestic energy production in most years since 2010.[ix] Production held steady at around 70 quadrillion BTUs until around 2010 before growing quickly thanks to oil and gas. 2023 was a record year for the US, with output reaching 103 quadrillion BTUs.[x]

- UK oil production fell to a record, post 1970’s low in 2023, with production down 36% on pre-pandemic levels.[xi] Natural gas production is down 12% on pre-pandemic levels and is now lower than at any time in the 20th[xii] 2021 saw a record low for post-1970’s total UK energy production, as did 2023.[xiii]

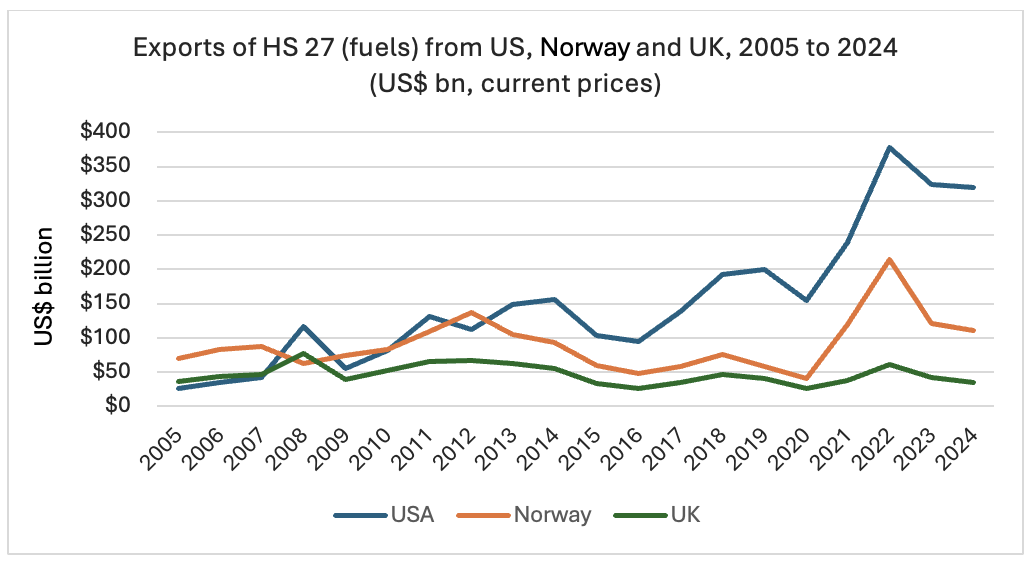

This is damaging enough for the UK economy, industry, skilled employment and tax revenues. But it also impacts exports. The chart below tracks the swift divergence in energy exports as between Norway, the UK and the US over the Brexit period.

Figure 2. The divergence of fuels exports: Norway, the UK and the US, 2005–2024

Source UN Comtrade, HS 27 (fuels). Accessed July 2025.

US energy exports diverged from the UK from 2016 (thanks to LNG) and then doubled from 2020. Norway’s exports tracked the UK’s until 2020, then swiftly parted company (thanks to natural gas and high prices). No-one would claim this divergence has anything to do with Brexit. It does, however, coincide precisely with the UK’s exit from the Customs Union.

But can energy alone sway total goods exports for the US and Norway, and thereby impact country-to-country comparisons? Apparently, it can.

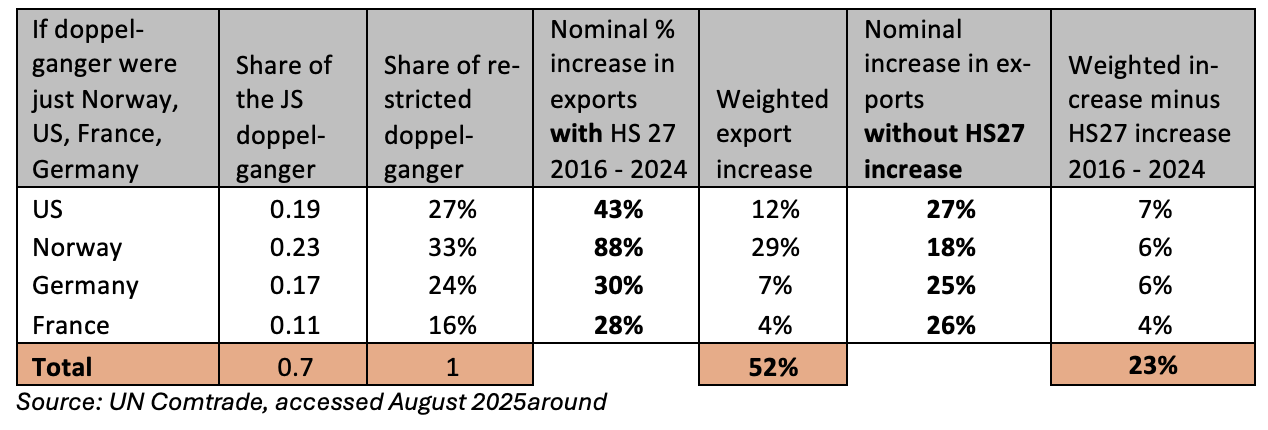

Figure 3. The role of fuel in post-2016 export growth for Norway and the US

(US $)

Source: UN Comtrade, accessed July 2025. Data is for HS 27 (fuels). Current prices. Excludes precious metals ( HS71).

- In nominal terms, Norwegian goods exports (minus precious metals) increased by a gigantic 88% from 2016 to 2024. But fuels account for 80% of that export increase. Remove the increase in fuels, and Norwegian goods-export growth drops from 88% to just 18%.

- Meanwhile nominal US goods exports increased by a far-above-average 43% from 2016 to 2024. But with a colossal gain of US$226 billion, fuels account for 38% of that increase. Take the increase in HS27 out, and growth drops from 43% to 27%.

So, almost one quarter (23%) of Springford’s doppelganger cohort involves a massive increase in exports from one country that was four-fifths due to energy. And almost two-fifths of the rapid US increase is down to the same factor. So how does that impact Springford’s doppelganger?

It is impossible to say without Springford’s methodology. According to my own, back-of-the-envelope calculation (see Table 2), more than half the weighted export growth for Norway, the US, Germany and France (70% of Springford’s doppelganger) disappears if you remove increases in fuel exports.

3. Errors and context

Then there’s the issue of errors. Everyone makes them, and it is inevitable when working with vast, complex data sets. But trade analysts have an inherent grasp of the industries that sit behind the raw trade numbers. This means they can (helpfully) spot mistakes when they appear in aggregate or comparative analyses.

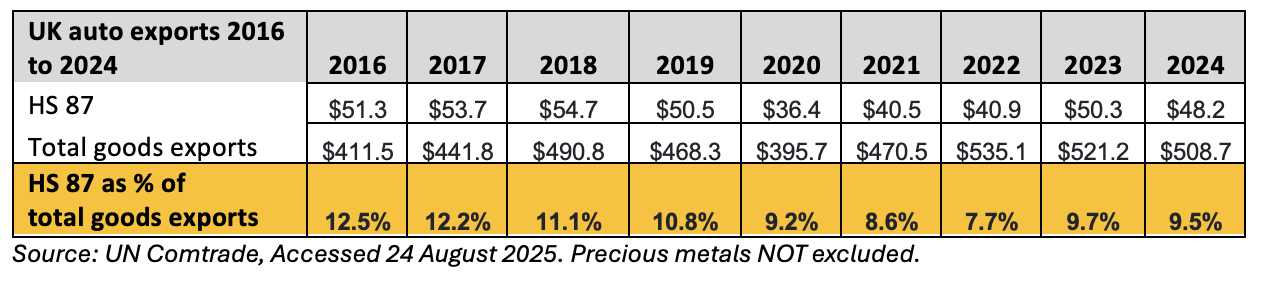

In his most recent publication – ‘The Economic Impact of Brexit Nine Years on – Springford has used the wrong data to analyse UK automotive exports since 2016.[xiv] His chart starts ‘losing’ large values of UK auto exports (HS 87) from 2020 onwards and is missing around £20 billion-worth by 2024.

His analysis thereby diagnoses a crash in automotive exports from 11% of UK goods exports in 2019 to just 5% in 2024. And from this, Springford observes that the UK auto industry has drastically underperformed peer economies from Brexit onwards, and concludes: “it appears that … [the UK] … has become less attractive as a site for [automotive] production to serve all markets.” [xv]

In reality, the data is drastically wrong and his commentary misplaced. UN Comtrade (the database he references) shows auto exports at almost 10% of UK goods exports by 2024 (see Table 3), not 5%.[xvi] The UK auto-export industry has mildly underperformed since 2017, nothing more. But the point is, a trade analyst would instantly spot that the chart was wrong, and it would never have progressed to publication.

Some data is not wrong, but still highly misleading. In the above paper, Springford says the UK sends ‘around half of its cars to the EU.’ But that’s a volume metric. In value terms, the EU accounts for just 33% of UK car exports.[xvii] Global (i.e. non-EU markets) dominate exports of premium British marques. What’s more, they have grown far faster than EU markets (8.1% p.a. from 2000 to 2019, versus 1.4% p.a.).[xviii] In auto terms, ‘Global Britain’ is already a reality – and the trend started 20 years ago.

Lastly, a trade analyst can provide context. The UK auto industry is set to benefit from a £20 billion investment surge announced in 2023.[xix] This will begin to deliver an impact from around 2026. What’s more, this investment will entrench that transition into a predominantly premium-brand industry just as Europe’s mass-market industry faces crippling competition from China.

What this means is that the UK auto industry is in a better strategic position than its EU competitors – and that’s before the US tariff differential emerged. But this context is entirely absent from model-derived economic analysis.

4. The misattribution of causation

Finally, trade analysts can help economists avoid misinterpretation.

As of last year (2024), the single biggest post-Brexit ‘drag’ on UK exports is chemicals. Exports were down £3.8 billion in EU markets compared to 2019 (2019 prices), and £3 billion in non-EU markets.[xx] These falls are in direct proportion to historic export values to EU and non-EU markets[xxi]. In other words, there is no bias towards falls in EU markets.

But this is hardly surprising to industry analysts who have observed a slew of closures in the UK’s once-mighty chemicals and petrochemical industry over the past three years. Sure, the new REACH system has been a £2 billion industry cost, and it is directly attributable to Brexit. But this is a one-off cost. Industry sources and press releases consistently blame high energy costs as well as weak demand and high labour costs.[xxii]

The point is that in 2025 and 2026, chemicals will likely be the single biggest drag on UK goods export data, but the causes are primarily the results of domestic policy settings. Blaming Brexit is just dishonest. What’s more, it obscures an unfolding but preventable industrial tragedy.

Finally, there’s the strategic misattribution of causation. In his Economic Impact of Brexit paper, publish in June, Springford points out that UK goods exports outperformed his doppelganger before 2021 but underperformed afterwards.[xxiii] Since this coincides precisely with the UK’s withdrawal from the Customs Union and Single Market, Brexit appears the obvious culprit.

But the timing coincides precisely with big shifts in UK export trajectories.

- Prior to 2020, aerospace was the UK’s fastest growing major export industry, growing by 4.9% p.a. (2000 to 2019).[xxiv] But this was the sector that went into sharp reverse from 2020 onwards.

- Prior to 2020, the UK auto industry was the UK’s second-fastest growing major export industry, and it grew quickly thanks to global markets. Then it suffered a decline almost as severe.

Together those two industries delivered 22 to 24% of UK goods exports up to 2019; a higher proportion than for any peer economy.[xxv] When both industries executed a simultaneous nosedive in 2020, the inversion of UK’s comparative trade performance became inevitable. And yet this basic industry point finds no place in publications that depict 2020 as inflection point in UK trade.

5. Answering paradoxes

Above all, a broad awareness of the goods behind the data can dispel apparent oddities in UK trade. In his latest publication on Brexit, Springford dwelt at length on the ‘paradox’ that … ‘Britain’s goods trade performance has been so markedly worse since it left the EU, but there isn’t a clearer hit to EU trade versus everywhere else.’[xxvi]

But if you analyse trade sector by sector it is instantly obvious why this happened.

- Some industry sectors are in decline for reasons unconnected or only partially connected with Brexit (chemicals, pharmaceuticals, computers and electronics). So, export ‘losses’ are evenly balanced, as between EU and non-EU markets.

- In some sectors, losses are confined to EU markets and there is a logical chain of causation between new trade barriers and lower exports. But these are either small (food, agriculture) or involve re-exports (clothing and footwear).

- Autos and aerospace account for the biggest losses until 2023. Losses in auto exports are slightly skewed towards EU markets, but losses in aerospace are massively skewed towards non-EU markets. These balance Brexit-related losses in food, agriculture and clothing.

Add all these ‘losses’ together, and the net result is that export shortfalls in EU and non-EU markets almost exactly balance each other in every year from 2021.[xxvii] There is no paradox about it.

Summary

Doppelgangers worked well when the international trading system was stable. But how are they supposed to be useful tools of comparison – let along diagnostics – when multiple disruptions occur simultaneously? Can they really isolate causation when domestic policy settings force a wind-down of major UK industries, specifically energy and chemicals?

The core of the matter is whether academic theory or commercial analysis provides a more reliable approach to trade analysis. Springford’s latest publication seeks general or theoretical answers to poor trade data.[xxviii] But answers can readily be found in company annual reports, industry insights and sectoral trade data. That’s where policy-makers should focus if they want actionable answers to current challenges.

And policy-makers should focus on these sources before it is too late. At present, the most dramatic ‘turns’ in UK trade data are the £20 billion-plus annual deficit in trade in oil and gas, and the semi-related wind-down of the UK’s once-mighty chemicals and petrochemicals industry. Happily – or, for some, unhappily – these are actionable insights.

The take-home is that theoretical approaches to UK trade analysis will continue to deliver misleading judgements so long as they are divorced from practical, industry insights. For the sake of national prosperity, it is time for economists and trade analysts to work together.

Phil Radford was a Senior Advisor at the Australian Trade and Investment Commission in Sydney from 2019 to 2023. He is the author of ‘The Quiet Triumph of British Engineering: Competitive advantage in premium cars, civil aerospace and power machinery.’ Civitas, October 2025. This is an extended version of a blog post published by UK in a Changing Europe in November 2025.

- Automotive and aerospace as a share of UK goods exports, 2016-2024

- The impact of fuel (HS 27) on doppelganger country growth rates, 2016 to 2024 (HS 71 excluded from all calculations)

- UN Comtrade data on UK auto exports (US$ billion)

[i] ONS: UK Trade in goods by Classification of Product by Activity, time series dataset, Quarterly and Annual up to and including 2025 Q1. Deflated using ONS IDEF deflators for machinery. SITC 7.

[ii] ONS UK trade in services: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted Q4 2023. Deflated using) ONS IDEF Services deflator. Calculated as Engineering Services’ (EBOP 10.3.1.2) plus maintenance and repair’ (EBOP 2). A cross check with Rolls Royce Annual Reports (2019 to 2023) shows Commercial Aerospace revenue falling from £8.1 billion in 2019 to £4.3 billion in 2021 (2019 prices). Assuming a 63% services/goods export split, this implies a drop in services revenue of £2.4 billion.

[iii] Combined deliveries of Airbus and Boeing commercial aircraft fell from 1606 in 2018 to 723 in 2020. For Boeing, see Boeing Media Room, Fourth Quarter Deliveries, Jan 2019 (Link) and Boeing Media Room, Fourth Quarter Deliveries, Jan 2021 (Link). For Airbus see Orders and Deliveries for respective years: (Link)

[iv] The US International Trade Administration reports the UK has the world’s second largest aerospace industry. ITA, UK Country Commercial Guide, Accessed October 2025. Link

[v] Airbus, Orders and Deliveries, December 2024. *Includes deliveries of 17 Airbus A380s in 2019 to 2021, when the program terminated.

[vi] Export losses (as compared to 2019) in aerospace exceeded losses in the auto sector in 2020 and 2021. In nominal terms, exports fell 27% in 2020 as compared to 2019, and 25% in 2021.

[vii] Reuters: Norway gas output hits to stay close to last year’s record levels, January 2025. Link.

[viii] More than 200 million cubic metres of oil equivalent in 2024, having peaked at just over 250 million in 2004. Ibid.

[ix] IEA: U.S. energy production exceeded consumption by record amount in 2023, June 2024. Link

[x] IEA: U.S. energy production exceeded consumption by record amount in 2023, June 2024. Link

[xi] GOV.UK: Digest of UK Energy Statistics. DUKES 2024, Chapter 1: Energy. Link Page 1.

[xii] GOV.UK: Digest of UK Energy Statistics. DUKES 2024, Chapter 1: Energy. Link Page 2.

[xiii] GOV.UK: Digest of UK Energy Statistics. DUKES 2024, Chapter 1: Energy. Link Page 1.

[xiv] See Springford: The Economic Impact of Brexit Nine years On: Was the Consensus Right? The Constitution Society. Figure 6, Page 18. The line for UK Automotive should finish in 2023 at around 10%, according to UN Comtrade, which is the source he cites.

[xv] Springford: The Economic Impact of Brexit Nine years On: Was the Consensus Right? The Constitution Society. Page 18.

[xvi] As an aside the remaining UK underperformance in auto exports would narrow still further – to around 1 ppt for 2017 to 2023 – if calculations omitted trade in gold . This is because UK gold exports (HS7108) surged dramatically during this period, from US$21.4 billion in 2020 to US$65.5 billion in 2023. In the same year the US’s were US$30 billion; Germany’s $10 billion; and Norway’s US$155 million. So, there would be only a minimal impact on the other principal countries in Springford’s doppelganger. UN Comtrade. Accessed July 2025.

[xvii] UN Comtrade, Accessed July 2025. Classified as HS 87.

[xviii] ONS: UK Trade in goods by Classification of Product by Activity, time series dataset, Quarterly and Annual up to and including 2025 Q1. Deflated using ONS IDEF deflators for the machinery sector, SITC 7.

[xix] SMMT: UK Auto manufacturing charges up with £20bn investment boost in 2023. November 2023. Link

[xx] ONS: UK Trade in goods by Classification of Product by Activity, time series dataset, Quarterly and Annual up to and including 2025 Q1. Deflated using ONS IDEF deflators for the chemicals sector, SITC 5.

[xxi] According to ONS, Chemicals (SITC 30) exports in 2019 were £16.3 billion to the EU, £12.5 billion to non-EU markets.

[xxii] Chemicals Industry Association, UK’s chemical industry faces stalling growth against backdrop of rising costs, sluggish growth, and Chinese competition. October 2024. Link.

[xxiii] Springford: The Economic Impact of Brexit Nine years On: Was the Consensus Right? The Constitution Society. Page 15.

[xxiv] ONS (2025) UK Trade in goods by Classification of Product by Activity, time series dataset, Quarterly and Annual up to and including 2025 Q1, May 2025, Deflated using ONE IDEF sectoral deflators (SITC 7)

[xxv] See page 19, Less than Meets the Eye. Policy Exchange, March 2025.

[xxvi] Springford: The Economic Impact of Brexit Nine years On: Was the Consensus Right? The Constitution Society. Pages 17 – 18.

[xxvii] See Less than meets the eye: The true impact of Brexit on UK trade. Policy Exchange, March 2025. Page 41 to 48.

[xxviii] Springford: The Economic Impact of Brexit Nine years On: Was the Consensus Right? The Constitution Society. Page 17.

Related