The Stringer: The Man Who Took the Photo, which lands on Netflix this week, opens with a line implying Nick Ut is a liar: “What you do know is what you didn’t take.” But is that really true? I’ve always thought the inverse makes more sense.

SPOILER WARNING: This article contains many spoilers for The Stringer.

This story is being brought to you as an ad-free preview. Go fully ad-free with a PetaPixel Membership today.

When a photographer takes a picture, the shutter flips up, rendering them blind for a millisecond. You don’t know exactly what you’ve shot until you see the photo. Therefore, when a photographer sees the frame they wanted in their viewfinder, they know they’ve missed it because the shutter wasn’t up. So perhaps the more accurate saying would be: “What you do know is what you missed.”

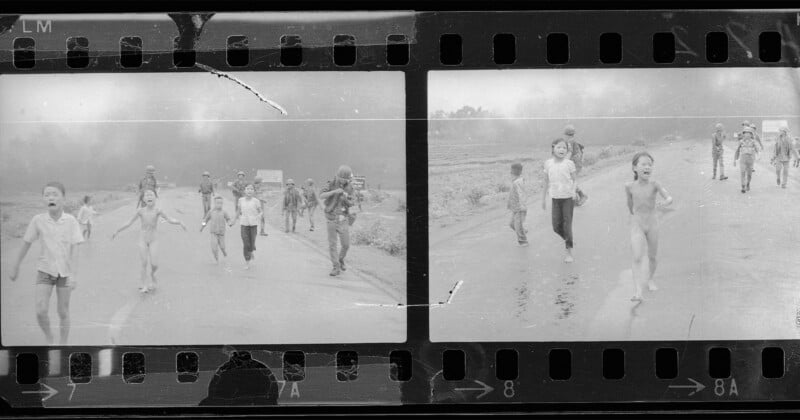

It’s one of the many questionable claims and statements made by The Stringer, a documentary examining the true authorship of The Terror of War, colloquially known as Napalm Girl. One of the Vietnam War’s most famous images, it shows a terrified Kim Phuc and her brother running through the village of Trang Bang on June 8, 1972, just after it had been bombed. Phuc had removed her clothes because the napalm was searing her back.

Associated Press

Associated Press

Produced by the VII Foundation and led by photojournalist Gary Knight, the documentary takes viewers on a gripping investigation that arrives at a devastating conclusion: photographer Nick Ut did not take the photo for which he won a Pulitzer Prize and unknown stringer Nguyen Nghe is the true author of the photo.

A still from The Stringer that shows freelancer Nguyen Thanh Nghe at the scene of Napalm Girl. Origin of the Claims: Carl Robinson

A still from The Stringer that shows freelancer Nguyen Thanh Nghe at the scene of Napalm Girl. Origin of the Claims: Carl Robinson

The Stringer came about because of one person: Carl Robinson. He was the photo editor at the Saigon Bureau the day the photos from Trang Bang arrived. Before the documentary, Robinson was best known as the man who rejected the famous photo because of its full-frontal nudity.

The established lore of Napalm Girl is that when AP darkroom editor Yuichi ‘Jackson’ Ishizaki developed the photo, he and Robinson got into an argument over whether the photo should be transmitted to the media because it showed Kim Phuc fully naked. Ishizaki told an office employee to go and fetch the chief of photos in Saigon, Horst Faas, to settle the argument. Faas immediately saw the power of the photo and sided with Ishizaki.

It was when Robinson was typing up the caption and credit information that he says Faas leaned in his ear and said, “Nick Ut. Make it Nick Ut.” Ishizaki, Faas, and a darkroom technician called Huan were all present with Robinson in the room that day. All are now dead apart from Robinson.

Robinson working at AP’s Saigon Bureau. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

Robinson working at AP’s Saigon Bureau. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

That Robinson disagreed with the decision to publish Napalm Girl is conveniently omitted from The Stringer. To this day, Robinson still believes AP made the wrong call wiring the image despite the undoubted impact the photo had; it became an anti-war symbol, and President Richard Nixon even mused whether the photo was “fixed.”

In an article for The Australian written this year, Robinson maintains the photo should never have been published, saying that other news organizations had “more discretion” by leaving the distressing images of Kim Phuc on the cutting room floor.

In a 2005 interview, Robinson reportedly said AP had “created a monster” by focusing too much on Kim Phuc, and not on all of the war’s victims. In 2022, he called the photo “pedo war porn” and railed against Ut, whom he called a “false idol.” In 2024, Robinson directed yet more anger against Ut, saying he “has gone all Hollywood, I don’t like that.”

Robinson was dismissed from AP in 1978 for unknown reasons. In his autobiography, he wrote that he had a “simmering anger, resentment, and bitterness, especially toward AP.”

None of the above is mentioned or brought up in The Stringer. The film instead presents Robinson as a man who has been wrestling with his conscience for 50 years because of the great secret that he holds.

Gary Knight, left, and Carl Robinson. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

Gary Knight, left, and Carl Robinson. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

Putting aside the fact that most would argue Robinson made the wrong call on the most important photo he ever worked on and the fact he has expressed bitterness toward Ut and Faas, what other evidence does Robinson have? He says it was an “open secret” among Vietnamese staff at AP and NBC that the photo had been wrongly attributed, a claim disputed by others who were working in Saigon. He also claims that he raised the issue repeatedly to colleagues and directly to Ut himself. There are some Vietnam War hacks in the documentary who back up Robinson’s claims, but there are others who say they’ve never heard of them, or say they’ve heard of them but dismiss them.

Horst Faas

In an attempt to explain what motivated Faas to change the credit on the photo, the film’s protagonist, Knight, explores Ut’s brother, who was killed while on assignment for Faas, which made the photo editor loyal to Ut.

“Giving this image to Ut wouldn’t make up for his brother’s death, but is it possible Faas thought it would make Ut more secure at AP?” Knight writes in an article for Rolling Stone.

Knight also highlights the photo agency battle playing out in Saigon; AP was reportedly “losing the play” to UPI in 1972. “This was not a moment for an ‘icon of all time’ to be transmitted with the byline of a stringer,” says Knight.

Horst Faas. | Wikipedia

Horst Faas. | Wikipedia

The AP’s chief of photos in Saigon, Horst Faas, is perhaps the most famous photographer of the Vietnam War. Faas, originally from Germany, spent more time in Vietnam than any other foreign journalist and his portfolio — including his iconic portrait of a young American soldier bearing a “War is Hell” headband — is the stuff of legend.

But The Stringer takes aim at Faas more than anyone else in the film. Knight makes the incendiary claim that Faas was regularly in the business of taking photos from local Vietnamese stringers and putting his own credit on them. In the Rolling Stone article, Knight says that fellow photojournalist legend Tim Page, with whom Faas was friends, told him that Faas would take credit for pictures that weren’t his. Page died in 2022.

“Had Faas grown to rationalize occasionally changing the credit on photographs over nearly a decade of war?” Knight asks. “Would this explain how he might have taken something from a stringer he didn’t know, given AP and the younger brother of his dead colleague the kudos, and enhanced his standing at the agency?”

Nguyen Nghe – The Stringer

The documentary goes into detail about the hunt for Nguyen Nghe, which it names as the real author of The Terror of War. Nghe is now an elderly man in ill-health, but he and his family strongly believe that he is the photographer of Napalm Girl.

The film explains that Nghe was a media professional who had even received training in the United States after he joined the South Vietnamese army.

Nguyen Thanh Nghe as a young man. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

Nguyen Thanh Nghe as a young man. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

Nghe’s story is this: he took the famous photo in Trang Bang and his brother-in-law, Tran Van Than, who worked for NBC, took the film to the AP office and was paid $20 for it while also being given an 8×10 print of the image. Six months later, he heard about the photo’s popularity and its misattribution, but when he went to find the print AP gave him, his wife had thrown it in the trash.

“Why do you have this photo?” Nghe’s wife reportedly asked him. This is vexing; if Nghe was a trained photographer and freelancing for Western media while an almighty war is raging in the country you live in, then surely it would be obvious to his wife why he had a photo like that?

And if it was an open secret among the media in Vietnam that Ut didn’t take the photo, then wouldn’t Nghe have been aware of the photo and the impact it was having immediately? After all, his brother-in-law worked next door to AP for NBC.

Nguyen Nghe, pictured, says he is the true author of the photo. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

Nguyen Nghe, pictured, says he is the true author of the photo. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025  A still from The Stringer that shows freelancer Nguyen Nghe at the scene of Napalm Girl.

A still from The Stringer that shows freelancer Nguyen Nghe at the scene of Napalm Girl.

And then there are Nghe’s credentials. The film goes out of its way to highlight his U.S. media training — even flashing his film lab certificates on screen. Knight goes so far as to claim that Nghe was the “most accomplished photographer” on the road that day, a blatant lie. Yet despite this emphasis, the film never shows a single additional photograph taken by him. In fact, Nghe told the AP via email that Napalm Girl was the only image he ever sold to any international outlet, which directly contradicts the film’s own claims.

Nick Ut

Throughout The Stringer, Ut is portrayed as the man who knows he’s lying. But while Ut is best known for Napalm Girl, he has a remarkable portfolio featuring other famous photos including Paris Hilton crying the back of a police car, James Hunt and Niki Lauda smiling together before the famous crescendo of the 1976 Formula 1 season immortalized in the movie Rush, and photos of OJ Simpson arriving at court.

Contrast this with Nghe: the documentary can’t produce a single other photograph he took. Like many Vietnamese photographers, Nghe would have lost a great deal during the Fall of Saigon in 1975. But the absence of any other work is difficult to comprehend.

The Reenactment

Ultimately, the first two-thirds of The Stringer is a game of he said, she said. But in case the viewer was not yet convinced, Knight hires a team of experts to forensically recreate June 8, 1972, and ultimately prove once and for all that Ut did not take the Napalm Girl photo.

The detailed recreation of that day is damning, as it appears to put Ut away from the scene of Napalm Girl.

Using a satellite image taken five months after the photo was taken, the team from Index Investigations attempts to map out the sequence of events. But while landmarks and distances are presented as fact, AP says it is impossible to distinguish the exact locations and measurements. At the very least, a margin of error should be built into the findings.

The reenactment that appears in the film. | INDEX Investigation/Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

The reenactment that appears in the film. | INDEX Investigation/Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

A figure in the footage shot by British TV station ITN is key. If it is Ut, then it puts him far from the scene of the Napalm Girl photo. After a cut in the footage, we see Ut coming from that same direction, making it appear that he couldn’t have shot the photo.

But we don’t know how long that cut was. Unlike modern digital cameras, there are no timestamps or metadata. Crews working in the field had to be careful they didn’t run out of film. The children, who are all in shock, are zig-zagging around and stopping when they encounter people. It is therefore difficult to know the exact timing of their walk out of Trang Bang and impossible to know the media’s movements — including Nick Ut’s.

The Camera

Perhaps the most compelling piece of evidence that Ut did not take Napalm Girl is the mystery of the camera used to take the shot.

Ut himself has said that he was carrying four cameras that day: two Nikons and two Leicas. After forensically analyzing the surviving negatives, AP’s own investigation declared it was unlikely the photo was taken on a Leica, the camera that Ut has always said he used.

Instead, AP finds it likely that the photo was shot on a Pentax. This is because film that’s been run through a Pentax tends to have slightly rounded corners. Although Nikons can reportedly show similar characteristics.

A Pentax that could have shot ‘Napalm Girl’ is produced in ‘The Stringer’. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025

A Pentax that could have shot ‘Napalm Girl’ is produced in ‘The Stringer’. Courtesy of Netflix © 2025  The two surviving frames of ‘Napalm Girl’ held by the AP.

The two surviving frames of ‘Napalm Girl’ held by the AP.

Ut says that he did carry a Pentax, namely his slain brother’s, which was gifted to him by his widow. But The Stringer spends surprisingly little time on this intriguing storyline. Perhaps that’s because it was AP that flagged this finding.

A Documentary Worth Watching, With Caveats

It’s impossible to prove with absolute certainty who took the photograph in Trang Bang that day. Personally, I believe there should be a statute of limitations on photo-credit disputes. Once fifty years have passed — and many of the key figures are no longer alive — you shouldn’t be able to drag the reputations of people or organizations you clearly hold a grudge against.

Since The Stringer presents a one-sided case with virtually no counter-arguments throughout the film, the vast Netflix audience will likely come away from the movie believing its version of events. Therefore, it is important to scrutinize the evidence put forward by Gary Knight and the VII Foundation.

To my mind, it’s utterly reprehensible that you would wait for the deaths of Horst Faas, Tim Page, Yuichi ‘Jackson’ Ishizaki, and Hal Buell before airing these claims. At best, it makes you a coward, at worst it’s malevolent.

Robinson is hardly an objective player here; his axe to grind is unmistakable, yet The Stringer barely acknowledges his animosity toward Ut and AP.

Faas has always been a giant of press photography and has a reputation for compassion. Yet the film assassinates his character, labeling him a plagiarist.

As for Nghe, it is difficult to know what to make of him. Perhaps he really has been cheated out of a lifetime of accolades and adoration. Or, perhaps he did take a photo of Kim Phuc that day, just not the one he thought he did.

At the end of the film, Nghe’s daughter, Jannie, miraculously discovers a copy of the Napalm Girl photo that their mother supposedly kept after discarding the original print. But the image is actually a newspaper clipping from years later, identifiable by the accompanying photo of an adult Kim Phuc. The VII Foundation tells PetaPixel that the cutting is from the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, published in November 1982.

It’s a strange ending, and after feeling misled for so much of the film, I found myself questioning whether the moment was even genuine.

Should You Watch It?

Absolutely. The film offers a fascinating look at one of the most iconic moments in press photography. Its exploration of authorship, power and privilege, journalistic ethics, truth and memory, war, and dignity makes for an engaging and compelling hour and forty minutes.