It was one of the most provocative findings of the past decade in planetary science: a potential underground lake of liquid water beneath Mars’ South Pole. First reported in 2018 by a team using the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft, the detection of an unusual radar signal set off speculation about life beneath the ice—and raised hopes for usable water reserves to support future human missions.

Now, that landmark hypothesis is under scrutiny. A new radar technique deployed by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) offers a sharper, deeper look below the Martian surface—and casts doubt on the idea that the signal represented a subsurface lake. Instead, researchers say, it may simply be a patch of buried rock or sediment producing a deceptive reflection.

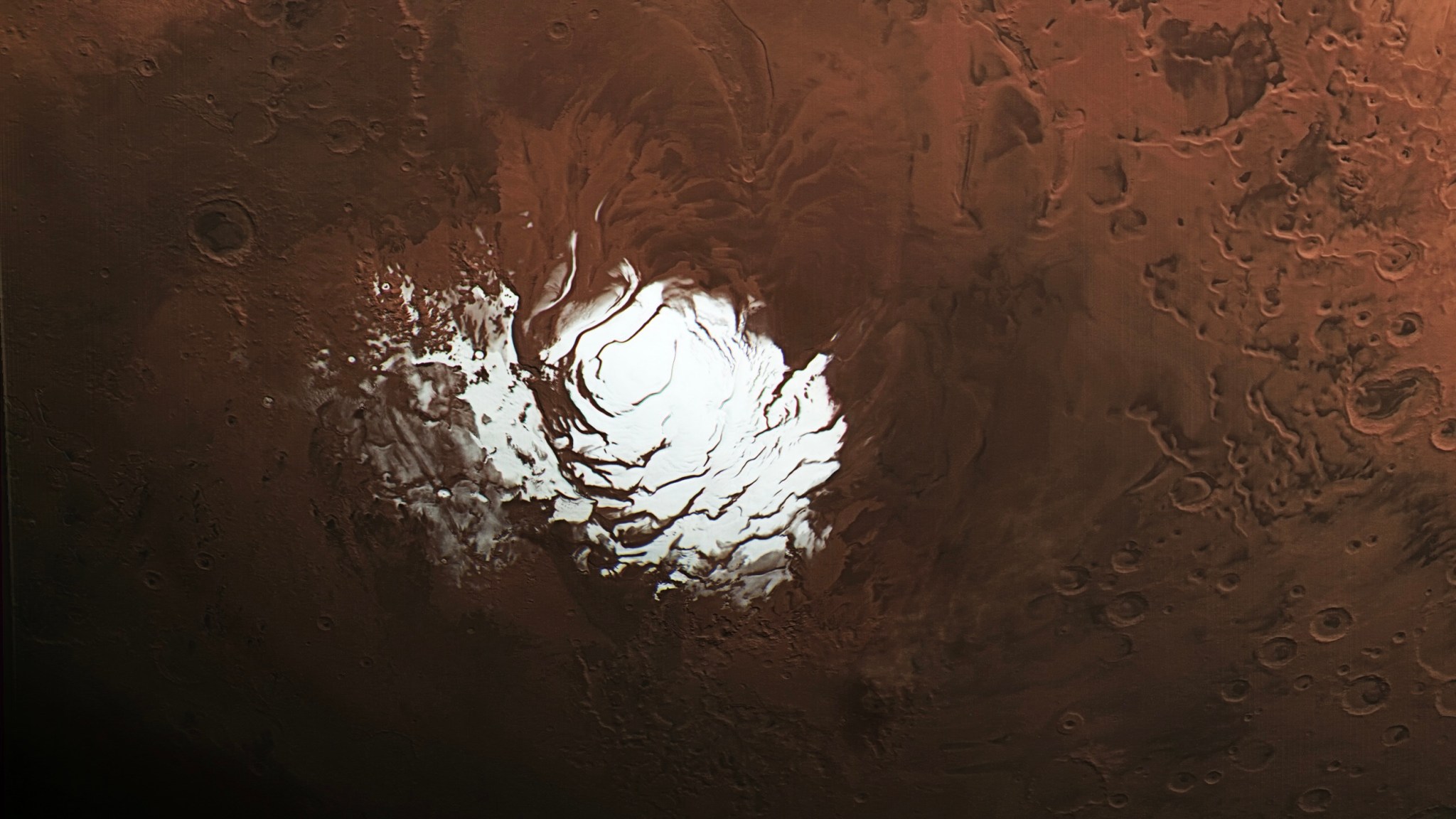

The European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter captured this view of Mars’ south polar ice cap Feb. 25, 2015. Three years later, the spacecraft detected a signal from the area to the right of the ice cap that scientists interpreted as an underground lake. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter captured this view of Mars’ south polar ice cap Feb. 25, 2015. Three years later, the spacecraft detected a signal from the area to the right of the ice cap that scientists interpreted as an underground lake. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

While the idea of a Martian polar lake may be fading, the upgraded scanning technique behind this new finding could prove more significant than the signal itself. Scientists are already using it to revisit other regions of Mars where water ice may be accessible—crucial not only for robotic missions but for human crews targeting the 2030s.

A Radar Breakthrough Cuts Through the Ice

The original 2018 signal was detected by the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Sounding (MARSIS) instrument aboard ESA’s orbiter. Its intense reflectivity was interpreted as evidence of a possible briny liquid lake beneath ice at Mars’ south pole. But that interpretation hinged on limited radar penetration and lacked cross-verification.

NASA’s SHARAD (Shallow Radar), onboard MRO, had previously scanned the same area without seeing any comparable signal. That changed after the SHARAD team implemented a specialized maneuver called a “very large roll,” rotating the spacecraft 120 degrees to enhance signal strength and reach deeper beneath the ice sheet.

“We’ve been observing this area with SHARAD for almost 20 years without seeing anything from those depths,” said Than Putzig, SHARAD co-investigator at the Planetary Science Institute, according to NASA.

When finally successful, the result was telling: SHARAD recorded only a faint return from the target zone—much weaker than MARSIS’ earlier data. Another scan of a neighboring area showed no signal at all. That inconsistency, scientists say, points toward a different cause for the strong reflection.

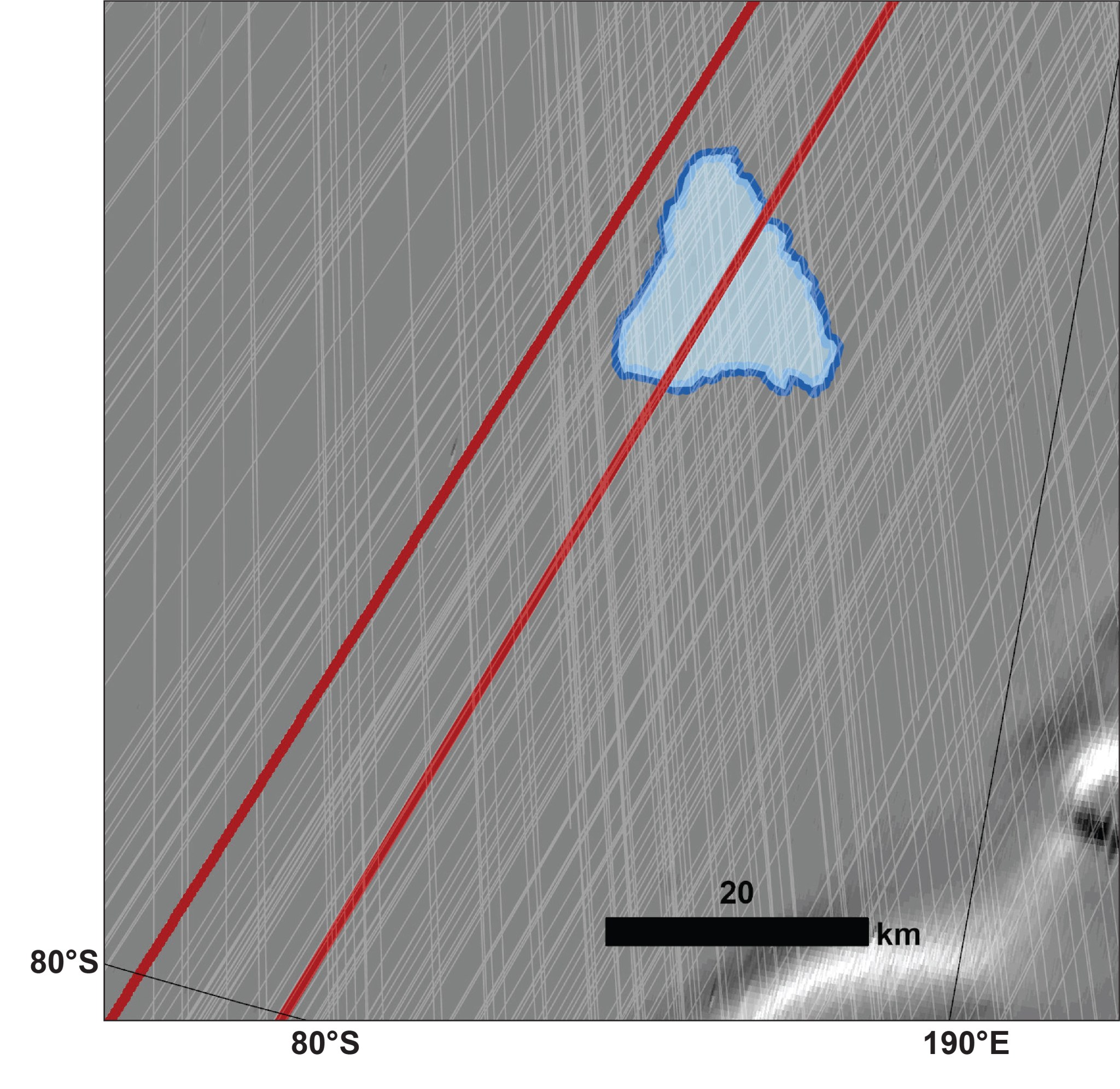

This map shows the approximate area where in 2018 ESA’s Mars Express detected a signal the mission’s scientists interpreted as an underground lake. The red lines show the path of NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which flew both directly overhead as well as over an adjacent region.Credit: Planetary Science Institute

This map shows the approximate area where in 2018 ESA’s Mars Express detected a signal the mission’s scientists interpreted as an underground lake. The red lines show the path of NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which flew both directly overhead as well as over an adjacent region.Credit: Planetary Science Institute

Instead of liquid water, the SHARAD data now points toward a relatively smooth patch of subsurface terrain on Mars—possibly volcanic rock—could be reflecting the signal in a similar way. As lead author Gareth Morgan put it, “while this new data won’t settle the debate, it makes it very hard to support the idea of a liquid water lake.”

From Polar Mystery to Equatorial Promise

With doubts growing about the south pole’s lake, scientists are refocusing on areas where subsurface ice may be more accessible—and more valuable for human exploration. That’s the goal of NASA’s Subsurface Water Ice Mapping (SWIM) initiative, which compiles two decades of data from MRO, Mars Odyssey, and the Mars Global Surveyor to identify buried ice in Mars’ northern hemisphere.

The SWIM project prioritizes midlatitude regions like Arcadia Planitia and Deuteronilus Mensae—zones that balance accessibility, thermal stability, and solar exposure. These locations lie between Mars’ cold, icy poles and its warmer equator, offering the best chance for both landing safety and resource extraction.

“This data allows us to draw that line with a finer pen instead of a thick marker,” said Sydney Do, SWIM project lead at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in NASA’s JPL feature.

The mapping effort assesses where five independent datasets—thermal readings, radar signals, hydrogen abundance, surface imagery, and neutron spectrometry—converge to suggest ice. Areas with consistent signals across multiple instruments are considered high-priority Mars landing sites for further exploration.

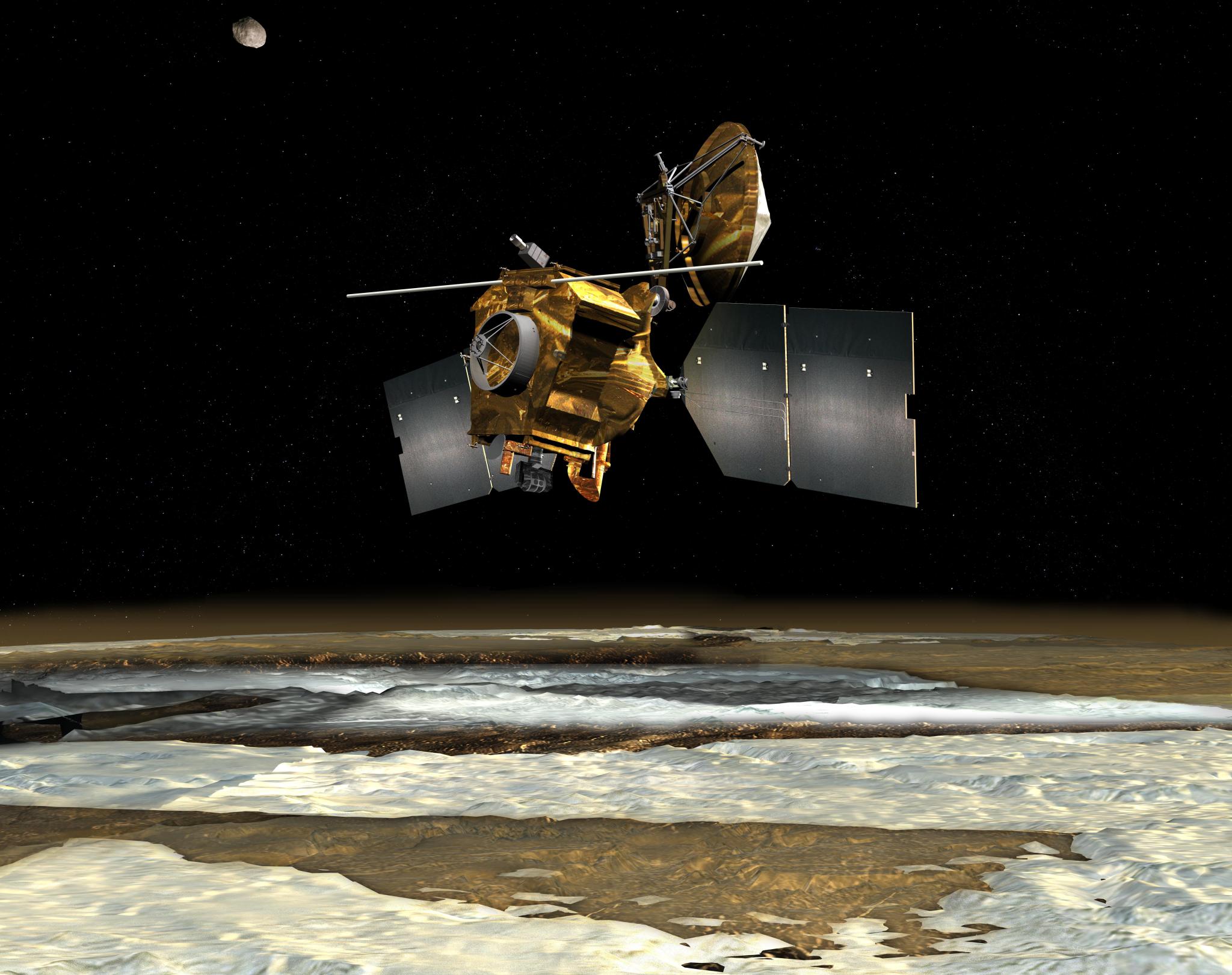

An antenna sticks out like whiskers from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in this artist’s concept depicting the spacecraft, which has been orbiting the Red Planet since 2006. This antenna is part of SHARAD, a radar that peers below the Martian surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

An antenna sticks out like whiskers from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in this artist’s concept depicting the spacecraft, which has been orbiting the Red Planet since 2006. This antenna is part of SHARAD, a radar that peers below the Martian surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

For future astronauts, this isn’t just about access to water for drinking. Subsurface ice on Mars could support fuel production, agriculture, and life support systems, reducing the need to transport massive supplies from Earth.

Mission Planning Now Starts Below the Surface

The SHARAD roll maneuver has emerged as a game-changing capability. Originally considered risky due to the spacecraft’s configuration, the roll allows radar energy to bypass the orbiter’s structural interference and penetrate deeper into Mars’ layered terrain. Engineers at JPL and Lockheed Martin developed the maneuver to enhance SHARAD’s reach while preserving spacecraft stability.

According to NASA, the technique is now being applied to other regions, such as Medusae Fossae, a vast equatorial formation that yields almost no radar return. Some researchers believe this could indicate deeply buried ice deposits or layers of volcanic ash—a puzzle future missions will seek to unravel.

NASA’s Mars Exploration Program is also collaborating internationally on a potential Mars Ice Mapper mission, in partnership with agencies in Italy, Canada, and Japan. The goal: a dedicated satellite to track shallow water reserves across the planet’s surface, improving landing zone assessments and refining resource maps.