“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” This saying is often wrongly attributed to Albert Einstein. It’s unclear who coined the expression, but – regardless – it applies perfectly to the Euro. The countries that make up the Euro zone have highly unequal levels of government debt. Last year, Germany’s debt was 63 percent of GDP, far below Italy (135 percent) and Spain (102 percent). Whenever a bad shock comes along, Italy and Spain are unable to issue debt at low interest rates and – as a result – are always on the verge of a debt crisis. The ECB, which wrongly sees any debt crisis as an existential threat to the Euro, has pivoted to cap yields with its TPI anti-fragmentation tool, which allows it to push yields back down to what it deems fundamentally-justified levels. It should surprise no one that – with this distortion to incentives – the number of high-debt countries is growing rapidly. French debt was 113 percent of GDP last year and is forecast to rise further.

A few weeks ago, I wrote a series of pieces on Euro breakup. I began by explaining that the ECB – because it equates survival of the Euro with avoidance of debt crises – no longer represents the interests of low-debt countries like Germany. The only way to fix this imbalance in my opinion is for Germany to exit the Euro or – at least – to credibly threaten exit. This would force debt write-downs in Italy and Spain, which would create the fiscal space needed to confront external threats like Russia and China. At a time of elevated geopolitical risk, Europe can no longer afford to blunder along in its current debt delusion.

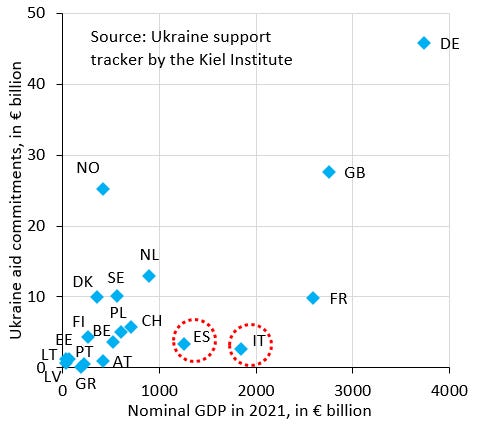

Needless to say, my posts met with strong disapproval. I’ll summarize the main pushbacks below, but let’s be clear about one thing: the status quo is unsustainable and will end. My favorite way to illustrate this is the chart above. The horizontal axis shows nominal GDP in 2021. The vertical axis shows aid commitments for Ukraine across key European countries. Despite their large size, neither Spain (ES) nor Italy (IT) provide meaningful aid. Both countries claim they don’t have a debt issue, but actions speak louder than words. These countries’ lack of fiscal space – and their refusal to address this – makes them a geopolitical liability. Unless this gets fixed, Europe will be increasingly marginalized on the global stage.

There’s three broad categories of pushback to my Euro breakup view:

-

Divorce will be too painful. Of all the arguments, this is the weakest one. Both Italy and Spain want to preserve the status quo because it allows them to extract rents from Germany. They thus have every incentive to portray Euro breakup as apocalyptic. Low-debt countries should see this for what it is: negotiation. Once Germany pulls the plug on the Euro, Italy and Spain will have no choice but to cooperate because they’ll need cash to manage large devaluations and debt write-downs. Their ex post behavior will be very different – and much more cooperative – from what they signal ex ante.

-

Euro breakup will end the EU. You don’t need a single currency for common foreign policy or defense. You also don’t need it for a single market or even banking union. It’s important to remember that the Euro is just a system of exchange rate pegs. All it really does is eliminate exchange rate volatility, which companies around the world deal with routinely and hedge at low cost. Of course, you can read all kinds of things into the Euro, including a geopolitical role. But – again – this is just ex ante bluster by high-debt countries that want to keep extracting rents from Germany. It’s time to call their bluff on this.

-

Euro breakup means war. It’s true that anti-German sentiment is very strong in the Euro zone, but I don’t think that’s a reason to shy away from breakup for two reasons. First, there’s a lot of ex ante bluster here also. This rhetoric will change when cash is needed. Second, my impression is that anti-German sentiment is building over time, because politicians in high-debt countries blame Germany for their inability to spend. This scapegoating is dangerous to the European project. Better to let everyone do the fiscal policy they feel they’re entitled to and then let them suffer the devaluations they deserve.

Let me be clear. I’d much rather keep the Euro and avoid the pain of breakup. But it should be clear to everyone by now that Spain and Italy are unwilling to do what it takes to get their debt levels down. As the chart above shows, there’s plenty of private wealth that can be taxed to do this. The issue is quite simply an unwillingness to do so, which is exacerbated by these countries’ influence at the ECB. All this perpetuates a status quo that’s broken and weakens the EU over time as other geopolitical actors forge ahead. Better to accept what doesn’t work and replace the system of fixed exchange rates that we call the Euro with floating exchange rates.

Let me close by reiterating the advantages that Euro breakup brings. First, it removes the Euro from the list of grievances populists in high- and low-debt countries have. Second, debt write-downs will create fiscal space that will permit Italy and Spain to participate in the defense of Europe and make burden-sharing across countries more equitable and sustainable. Third, transparency on debt has suffered immeasurably as high-debt countries have been shielded by the ECB. Compromised debt sustainability analyses that use artificially low interest rates (thanks to ECB yield caps) and words like “fragmentation” will be things of the past. Markets will again be the only arbiter of debt sustainability, holding politicians accountable for their actions.

Divorce is painful. It’s better avoided. But – if the marriage is bad – it’s better than the alternative.