“Even as us kids danced around the flames, there were real life monsters watching from the shadows.” “I nearly went and sat with her but because of the peer pressure from others I didn’t. “

“I nearly went and sat with her but because of the peer pressure from others I didn’t. “

It’s a memory that flickers in his mind’s eye. The moment eight-year-old Steve Diggle came face-to-face with Myra Hindley and Ian Brady. The Buzzcocks frontman spent his youth gadding around the terraced streets of Bradford, east Manchester – a place he describes as ‘the real Coronation Street’ which influenced his politics and outlook on life.

And though he recalls his formative years as a happy time, he remembers one Bonfire Night with startling clarity and grim hindsight.

“We used to have a croft at the end of the street with all the wood on. And this blonde woman came and sat down on this box.

“Obviously it was Brady who then said: ‘Come and sit next to Myra’.

Moors Murderers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady(Image: PA)

Moors Murderers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady(Image: PA)

“I didn’t realise of course. You don’t realise until much later.

“There were about five of us, cousins, friends, you know. But we were only about seven or eight.

“I nearly went and sat with her but because of the peer pressure from others I didn’t. Somewhere else I might have sat down but luckily I didn’t.”

It’s an episode Steve also recounts in his book Autonomy: Portrait of a Buzzcock.

“The chilling reality for kids of my age was that the Moors Murderers’ Manchester was our Manchester,” he writes.

“They plucked their victims from the very streets I grew up in, all to the east and southeast around Gorton, Ancoats and Longsight. So it’s not really surprising that one day I’d end up seeing them with my own eyes.

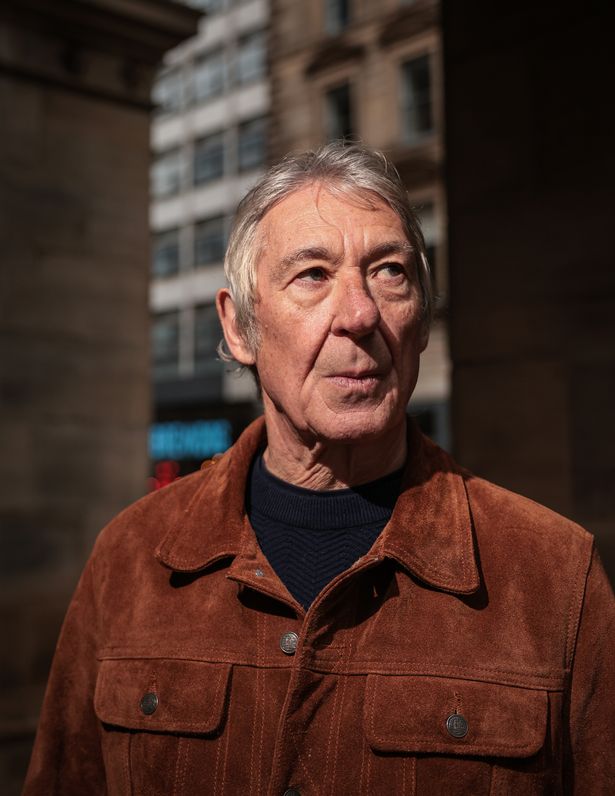

Steve Diggle(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Steve Diggle(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

“This was a bit later, when I must have been maybe 8 or 9. It was at a bonfire at the end of our street, and I remember seeing this Teddy Boy-looking bloke with this blonde woman.

“It was just those two watching us kids run around the bonfire, which even at the time I thought was a bit odd.

“They were sat on an old broken wardrobe, there to be chucked on the fire, going, ‘Come and sit next to Myra.’ I never sat with them, and I’m not sure any of the other kids did either, I just remember them being there, and I only mention it because that’s how frighteningly easy it must have been for them to do the horrendous things they did.

“It’s one of those weird, creepy memories that only pieces itself together years after the fact. Thinking back and suddenly realising ‘F***, that was them!’. But it happened.

“Even as us kids danced around the flames, there were real life monsters watching from the shadows.”

Manchester: Bradford, Hutchins Street, Victoria Gardens – 1963(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Manchester: Bradford, Hutchins Street, Victoria Gardens – 1963(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Steve says his parents also encountered Brady and Hindley.

His “bighearted” mum ran a children’s shop in the area and always let customers buy on credit – even Hindley’s mum, who lived nearby. While his delivery driver dad got “roped into decorating Brady’s bedroom”, years before details of his vile crimes were ever known.

“My dad knew his stepdad who told him, ‘Eric, this kid’s a nightmare, he’s just coming out of Borstal.’ So because my dad was good at wallpapering he asked if he’d help get Brady’s room ready, which he did,” he writes in Autonomy.

Speaking to the Manchester Evening News 60 years later, Steve says the Moors Murders put “a dark cloud on everything”.

“You had to rethink your life then and think ‘f**k, there’s people like that about’,” he says.

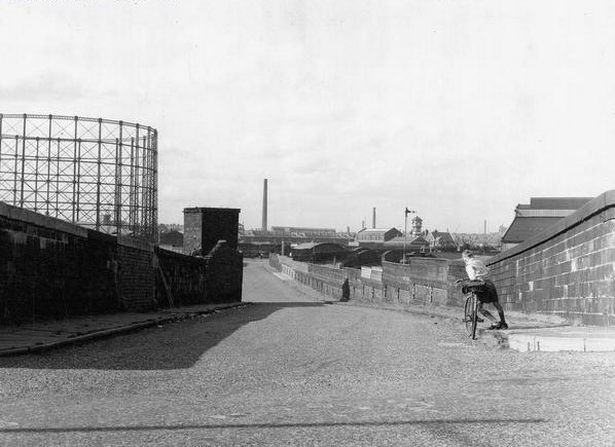

Gas holders in Bradford, Manchester(Image: Manchester Libraries and Archives)

Gas holders in Bradford, Manchester(Image: Manchester Libraries and Archives)

This close encounter is a memory he can’t escape, but it’s far from the most important part of Steve’s reminiscence about the east Manchester of the 1960s.

As a child born at St Mary’s and raised in Longsight and Bradford, he says it was a ‘fantastic’ childhood.

“Manchester is so modern now – all concrete. But it was all proper terraced streets back then,” he says. “Very Coronation Street.

“It was fantastic growing up in that kind of place. And obviously that left a Manchester mark on me.

“You had Belle Vue right at the end. I lived round the corner opposite the police station and the fire station. Belle Vue was an amazing thing looking back with the zoo. It was like Disneyland in the middle of all this industry.

“Our street was near The Bradford Hotel, which was on the corner. A big pub that looked like a beautiful palace.

Bradford Hotel, Mill Street, Bradford, east Manchester, 1964(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Bradford Hotel, Mill Street, Bradford, east Manchester, 1964(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

“Round there it was that thing where people would go into work all day and the pub all night. And in the summer the smell of the beer and cigarettes was better than any Chanel perfume.”

Living in close quarters with his working class peers and struggling families, Steve says he found himself observing from a young age.

“There used to be people taking their two weeks holiday to mend the car,” he says.

“You’d see cars on bricks. That was poetry to me. It was hardship and it was poetry.

Manchester: Bradford, Grey Mare Lane, west side – 1962(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Manchester: Bradford, Grey Mare Lane, west side – 1962(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

“It was something else growing up with that kind of thing. That impacted on my songwriting I think.

“But you never felt hard done to. That was the poetry of life to me – the reality of it.”

It was this poetry that first drew Steve to music and books.

He grew up on a diet of The Beatles, The Kinks, Bob Dylan and The Who and with authors and poets like HG Wells, Wilfred Owen and latterly James Joyce and George Orwell who sparked his interest in politics and philosophy.

“Once you’ve read stuff like Orwell and Joyce there’s no turning back. You think there’s got to be more to the world than this,” he says.

Manchester: Bradford, Barmouth Street, from Port Street, facing east – 1964(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Manchester: Bradford, Barmouth Street, from Port Street, facing east – 1964(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Working class heroes like George Best inspired him to think big. While an older lad on the street with a scooter moved him towards the Mod style.

“Manchester had this wonderful post war feeling and a great spirit. And that was amazing growing up in all that.”

It’s this attitude to life that Steve says influenced his songs like Why She’s a Girl From the Chainstore – which references sociologist Basil Bernstein, who theorised that middle-class students have an advantage because their language style is more aligned with the formal style used in schools.

“Facing Bernstein’s barrier/Waiting for someone to marry her” Steve growls in that 1981 classic.

Steve Diggle(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Steve Diggle(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

“A lot of my songs were political. Not straightforward finger pointing things but there’s a lot of undertones of politics in there.

“Harmony In My Head’s is about self rule. The Pistols were singing ‘anarchy in the UK’ I was saying you’ve got to rule yourself, not the government. You need to find yourself. That’s your country – your body.”

As a teenager, Steve worked briefly in an iron foundry but says: “I was always interested in music, not really interested in having a job.”

As such, he answered an ad for a bassist in the Manchester Evening News and met his future bandmates Pete Shelley and Howard Devoto at the Sex Pistols gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall – something we’ll explore in detail in the second part of our interview.

Manchester: Bradford, Nelson Street from Score Street – 1964(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

Manchester: Bradford, Nelson Street from Score Street – 1964(Image: @Manchester Libraries and Local Archives)

And for a young songwriter, the Manchester of the 1970s was an inspiring place. But Steve says the city today is a far cry from the one he knew then.

One of his most famous songs Harmony in My Head – penned in 1975 – was inspired by a stroll down Market Street in Manchester city centre.

“Manchester now reminds me of 1984 to four or something,” he laughs. “I remember when the Arndale Centre came up and you felt alienated by that.

“When I wrote Harmony in My Head it was about walking down Market Street. It was the cacophony – that was the harmony. The whole of life was there.

The Bradford Inn, Manchester(Image: MEN MEDIA)

The Bradford Inn, Manchester(Image: MEN MEDIA)

“All the people in that street, that’s the sound of life. The percolation of sound in that Market Street was like the whole of life was there.

“I’ve just been all around America and that’s full of glass skylines and Manchester’s like that now.

What freaks me out is I walk down Aytoun Street and remember there’s a police station and a pub – you’re half way down the street and a glass pyramid pops out. It’s all impersonal but it’s the same all over the world. There’s something beautiful but something impersonal about it all.

“From coming from those lovely streets of Bradford where it had a heart and soul, it seems so impersonal now. I mean it’s what they call progress, but is anybody any happier?”

Steve’s memoir Autonomy: Portrait of a Buzzcock is out now.