If Vladimir Putin attacked us we would still be up and running,” shouts Ed Bissell over the roar of the fans cooling down the computers in a hall the size of a football pitch.

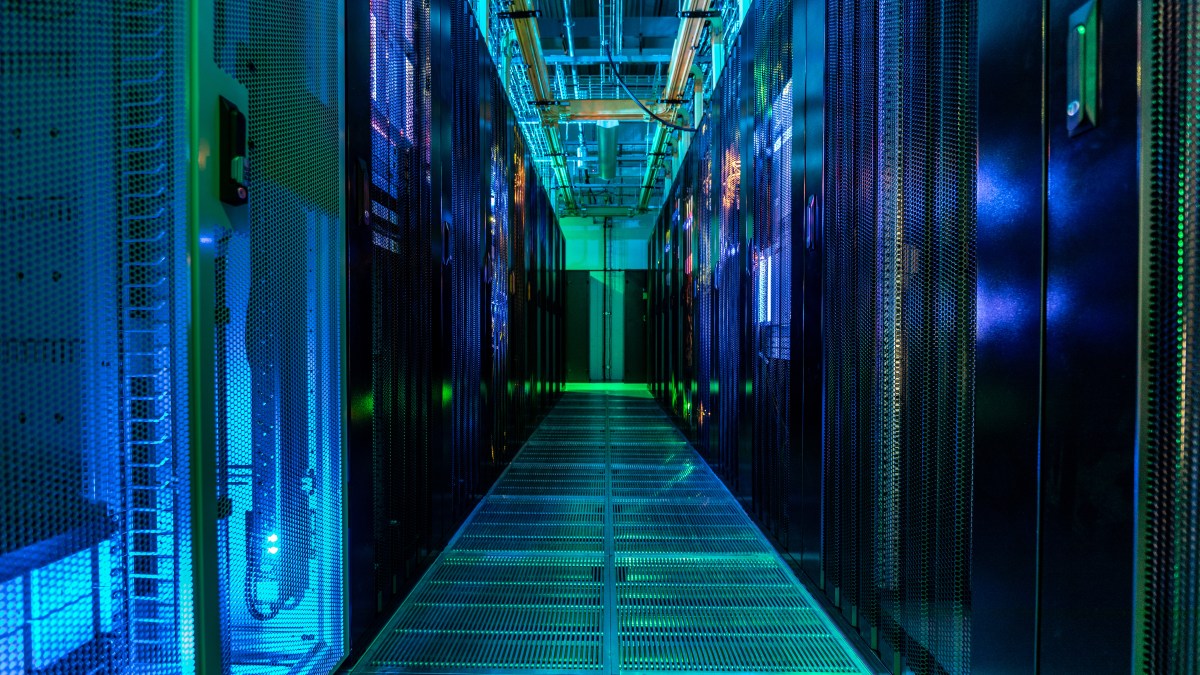

Before me is a sight few people outside Britain’s booming data centre industry have witnessed — row after row of computers stacked in racks the height of a tall fridge-freezer. These do not look like the desktop computers you might have at your home or office. Rather, they are slim black units nicknamed “pizza boxes”, stacked horizontally with green lights blinking on and off to signal the hive of activity inside.

Each pizza box contains a circuit board, hard drives and the most powerful microchips in the world — the processors that run millions of calculations a second to deliver artificial intelligence to our offices, governments and mobile phones.

Plants such as this one, run by the company Stellium on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne, are springing up across the country. There are already more than 500 data centres operating in the UK, many of which have been around since the Nineties and Noughties. They grew in number as businesses and governments digitised their work and stored their data in outsourced “clouds”, while the public switched to shopping, banking and even tracking their bicycle rides online.

But it was in 2022, when a nascent technology company called OpenAI launched ChatGPT, that the world woke up to the potential of AI and large language models to change the way the planet does, well, just about everything. It can do this thanks largely to advances in chip design by the US company Nvidia — now the world’s most valuable (and first $5 trillion) business. The trouble is, a typical ChatGPT query needs about ten times as much computing power — and electricity — as a conventional Google search. This has led to an explosion in data centres to do the maths. Nearly 100 are currently going through planning applications in the UK, according to the research group Barbour ABI. Most will be built in the next five years.

More than half of the new centres are due to be in London and the home counties — many of them funded by US tech giants such as Google and Microsoft and leading investment firms. Nine are planned in Wales, five in Greater Manchester, one in Scotland and a handful elsewhere in the UK.

Equinix, one of the world’s biggest data centre companies, valued at $81 billion on the US stock market, has just signed up to an 85-acre site in Hertfordshire, requiring 250 megawatts (MW) of power — enough to run the equivalent of about 200,000 homes. Bigger are yet to come: the derelict site of an old coal-fired power station in Blyth, not far from Newcastle, has been bought by the world’s biggest investment fund, Blackstone, to be turned into a data centre campus of up to 720MW.

The boom is so huge that it has led to concerns about the amount of energy, water and land these centres will consume, as residents in some areas face the prospect of seeing attractive countryside paved over with warehouses of tech.

AI evangelists argue this is a defining moment: laying down the foundations for a future where the most menial tasks — and some of the more creative ones — are automated. But as fears grow that we are in an AI hype bubble that could burst, others are asking whether this building boom is what Britain wants or needs. And can the world produce enough clean energy to feed the beast?

A chilled data fortress

Stellium launched on Cobalt Business Park, northeast of Newcastle, in 2016 and now runs four “data halls”, one of which I have been granted access to today.

I’d expected it to be hot and sweaty — a 21st-century version of William Blake’s dark satanic mills. In fact, it is spotlessly clean and kept cool and dry by a run of roaring air-conditioning units flanking the entire length of the room, drawing in the chilly air from outside. “That Newcastle air is pretty cold most of the time, which gives us an advantage over London,” says Bissell, Stellium’s sales director, who is dressed in jeans and a sports jacket. “It’s why Norway and Finland are really popular too.”

Above and below: the Stellium data centre, which opened on the outskirts of Newcastle in 2016

STEVE MORGAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

The chips inside the pizza boxes require a fantastic amount of electricity. Stellium uses only about 30MW at the moment, but this is growing and the whole Cobalt campus has the capacity for 180MW.

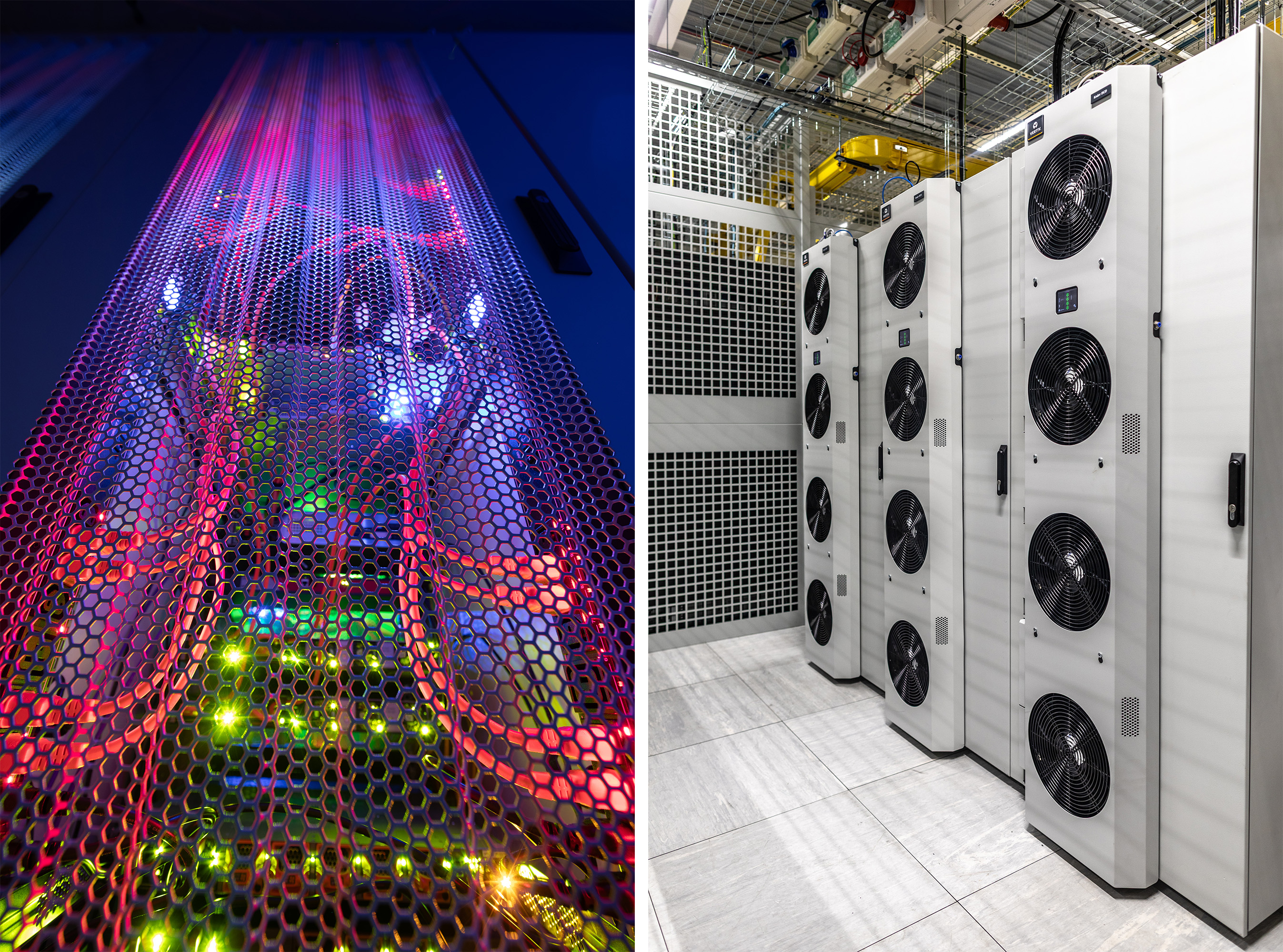

As the chips do their sums, they generate enormous amounts of heat. Older data centres were controversial because they used huge amounts of water in the cooling process, with the water being turned into steam. Stellium, like most modern centres, runs cold water around the chips in a closed loop, chilled from scalding to cool by constantly whirring fans in the back of the rack. “Without all this cooling equipment, the chips would just melt everything,” Bissell shouts over the din.

Customers ranging from banks to university labs and government agencies lease space here to house their super-powerful computers. A university or government department will typically use a 10KW rack, for which Stellium charges about £2,600 a month including the energy cost.

They could be calculating anything from cures for cancer to crime prevention. I say “could be” because security is so tight, even Bissell and his team have no idea what their clients’ computers are up to. “We’re like a very safe hotel — you rent a room and get up to what you like,” he says.

To enter this building, a hulking plain modernist box, I had to pass through no fewer than eight layers of security. That included a double round of crash-proof gates and a chicane-style road layout to prevent ram-raids even before I had got into the car park. A cheery mixed martial arts coach with heavy tattoos and china-white teeth standing on guard behind bulletproof glass checked my passport before allowing me in through an airlock-style entry pod.

Even if Russian or Chinese spies managed to infiltrate the data room, they would still face a struggle to access the computers. Each customer’s racks are housed in thick cages to prevent access. For the most sensitive, the cage is sunk deep into the concrete under the floor below and embedded into the ceiling high above us — “We call it ‘slab to slab’,” shouts a boiler-suited engineer. It should, in short, be too much even for Hannibal Lecter to defeat.

I’m not sure the building could do much about a Putin missile. But when Bissell talks of it surviving a Russian attack, he means an assault on Britain’s power infrastructure.

Ed Bissell at Stellium

STEVE MORGAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Stellium is connected to the national grid in one of the parts of the country best supplied by electricity thanks to the region’s industrial past. The shipyards and coalmines may have all long since closed, but they have left behind ample infrastructure such as electricity substations and connections to the grid. Furthermore, it is close to where the cables will hit land from the world’s biggest offshore wind farm array on Dogger Bank, which, when completed, will have the capacity to produce 3.6 gigawatts (3,600 MW) of power — enough to run approximately six million homes.

The Stellium campus is connected to two mains substations and has its own generators and five days’ worth of fuel to keep it going if the national grid went down — which it never does. These various sources of power are routed into the racks through thick cables, carried across the high ceiling in bright yellow ducts.

Whether the national grid can keep up with the demand to build data centres elsewhere in the UK is another matter.

• Keeping control of AI: the chronic risks to UK data infrastructure

Energy-hungry AI

ChatGPT and other AI models require two main types of computing power — or “compute” as they say in Silicon Valley. First, the compute to train the program; second, the compute to use that training to provide customers with the right answers. The latter is called “inference” in the world of AI.

Training — for example, giving an AI a million books and essays on the English constitution, or the road network of a big city, to learn and analyse — requires the biggest load of computing power.

In America, huge training data centres are being built in the middle of nowhere, where land is usually cheap. If there is a power substation nearby, American farmers have reportedly been selling off land to developers for as much as a million dollars an acre — more than their farms would return in a lifetime.

Typically these centres might use 1GW (1,000MW) of electricity — more power than is needed to supply the cities of London, Birmingham and Manchester put together. In a spending surge that far outstrips even the building of America’s railroads in the era of Andrew Carnegie, the so-called hyperscalers — Microsoft, Google’s owner Alphabet, Meta and Amazon — will have spent $370 billion building new data centres by the end of this year alone.

Inference requires a different approach. The student wanting ChatGPT to explain the origins of parliament’s first-past-the-post system needs an answer immediately. The driverless taxi heading towards a bend in Milton Keynes, even more so. Sending data down a fibre-optic cable is similar, in a way, to sending water down a pipe; the shorter it is, the quicker it reaches its destination, and the less energy it takes to get it there.

For inference, then, it makes sense to house the data centre as close to the customer as possible — primarily in and around main cities. In Europe, data centres are mostly in and around the busy cities they call “Flap-D” — Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam, Paris and Dublin.

Cages protect the computers; the microchips require sophisticated cooling systems

STEVE MORGAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

For now, the UK’s data centres remain largely focused on inference. Cameron Bell, director of European data centre business at the estate agency Savills, questions whether Britain will play host to the mega AI-training data centres now being built in the US: Britain has some of the most expensive electricity and land in the world, he says. “It just makes no sense unless we can find the energy.” So, while Britain is at the vanguard of data centre expansion, its lack of cheap energy from coal, nuclear or hydroelectric is holding it back from becoming an AI training superpower like the US.

National Grid says it has received only “one or two” requests to hook up training data centres in the UK, and that none has yet been granted. But it has had dozens of requests for the smaller inference sites —and they are asking for ever larger amounts of energy in anticipation of future needs.

• Fears grow over surge in electricity demand from data centres

Google versus the neighbours

Google chose the north London suburb of Waltham Cross for the site of its biggest European data centre, part of a £5 billion two-year investment in the UK. Like all hyperscalers, Google is secretive about what goes on in the facility. So I hopped on the Tube for a sniff around.

There are no road signs but eventually I find it on a 33-acre site by an A-road — an enormous dark green monolith the size of several Amazon warehouses. Multiple thick, intimidating layers of security fencing surround the perimeter and visitors have to pass through a gatekeeper’s lodge protected by bombproof glass.

Nowhere could I see a corporate name or any branding to identify the building, so I stop a hipster-slim couple in their thirties wearing Google-coloured lanyards to ask if this is the place. They refuse to say. “Who are you and why do you want to know?” asks the woman in an Irish accent.

Google’s largest European data centre is being built on a 33-acre site in Waltham Cross as part of a £5 billion investment programme

ALAMY

The place is crawling with workmen in hi-vis, however, who are more forthcoming. “It’s fantastic, isn’t it?” beams one proudly as we gaze up at the building’s eight towers, each topped by a gleaming silver chimney. For an architectural reference, think “Arizona supermax prison”. There are at least seven data halls on the site, each many times the size of the Stellium halls in Newcastle. Two are in operation already, with a light trail of smoke rising from their stacks.

The neighbours I meet seem less impressed than the workman. A ten-minute walk around the perimeter brought me to the Bury Green housing estate of tidy 1930s and postwar semi-detached houses. Cliff Richard lived here as a boy. For residents today, the sprawling Google complex has descended on attractive green belt farmland like a giant spaceship.

“It used to be known as Maxwell’s Fields — I’d bring my son down here when he was little to watch the combine harvesters,” says Martin Aylott, a 54-year-old former fireman. I meet him walking with his wife, Cathryn, by the New River Canal, which runs along Google’s perimeter fence. The banging and chugging of construction work is relentless from across the water. “It was a lovely walk,” Cathryn recalls. “You’d see wildlife, beautiful birds. Now we’ve got this.”

Lina Kleinaite, a physiotherapist, and her partner moved here from Essex in 2013. Her immaculate garden ends with a bed of nasturtiums, 30 yards from Google’s perimeter fence. “Some days the noise is just overwhelming,” she says. “It starts at 8am and goes on into the evening, sometimes into the night — it was 2am once.”

The noise should disappear on completion of the construction phase, which has been going on for about 18 months.

Paul Mason, a Conservative local council member for planning, says Google has invested heavily in the area, bringing much-needed jobs following the closure of Tesco’s headquarters in nearby Cheshunt.

In truth, while the construction of data centres can employ more than 1,000 people, once they are up and running only a few hundred at most are needed. The hope, however, is that if they have the computing power here companies such as Google will employ highly skilled engineers, designing AI and other programs.

Mason says Google has funded a new business centre next door to the Waltham Cross site that has attracted dozens of new start-up companies, and invested in improvements to local roads and a park. “They came in offering us about £10 million or £11 million, including the land value, but we were quite hardball and got them up to about £20 million,” he adds.

With such money on offer, British landowners, as in America, are rushing to try to sell their fields to the tech giants. At Savills, Bell says his phone rings multiple times a day with such inquiries. “Every half-hour I get a farmer and his mate on the line.” Mostly he has to break the news that, attractive though the views might be, Microsoft et al would find their land useless.

“I always get asked: why can’t we put them over there where nobody cares? The answer is that there is no electricity, no connectivity and nobody with the skills to build and operate them.”

If you are near plentiful energy and well-connected fibre-optic cable networks, you’re in the money. In a hotspot such as Slough, land with planning permission for alternative uses goes for about £6 million an acre. Sell it to a data centre and it could fetch up to £15 million. “A data centre operator would bite your hand off,” Bell says.

• Planning rules relaxed for big data centres in AI bill proposal

Power struggles

The Google complex I saw will require something in the order of 200MW of electricity to help run popular functions such as Google Maps, Search and Cloud. That is big by UK standards, but in the US it’s humdrum. Meta is building a site in Louisiana that will need 2GW — the equivalent output of two coal-fired power plants. Such requirements have put huge strains on local power grids in the US.

At his Colossus data centre in Memphis, Tennessee, also thought to have about 2GW of chips to feed, Elon Musk’s xAI has installed dozens of gas-fired turbines to generate 420MW of electricity — enough to power a city. He has even reputedly bought a power station overseas that he is planning to move to the site.

Bell says UK operators are starting to plan their own energy sources to get “behind the meter” — jargon for being self-sufficient and not reliant on the national grid. Digital Realty, a large data centre operator, is building a gas power plant to supply energy to its facility in Dublin, and others are expected to follow suit in the UK.

The American breed of giant AI-training data centres are draining electricity grids to the extent that local power prices have shot up. In the state of Virginia, home to a Washington DC suburb now dubbed Datacenter Alley, household energy prices are up 13 per cent on a year ago. It is becoming a serious political issue, with Democrats blaming Trump for cosying up to big tech and failing to protect families.

Addressing concerns about their impact on climate change, data centres say they try to use as much green energy as possible, and increasingly build their plants with biomass or other green energy provision on site. However, in reality they have to draw heavily on the local grid.

The International Energy Agency recently calculated that global carbon emissions from data centres will this year be about 180 million tonnes, surging to between 300 and 500 million tonnes by 2035. The energy and tech industries argue that this could be offset by new ways of saving electricity that AI may develop.

The UK grid uses a higher proportion of wind than most, but relies on fossil fuels on days of calmer weather. Steve Smith, chief strategy officer at National Grid, has the job of figuring out how to cope with the challenges these hungry new customers will face in the UK, especially as they grow to nearer the 1GW size. The problem, Smith says, is not that the UK does not have enough power, nor that customer prices will rise; rather that the power supply is not evenly distributed.

A large proportion of the UK’s electricity comes from Scottish generators, especially its wind farms, and flows down into England. Thanks to our industrial history, most of the pylons and substations that distribute it are set up to feed the north of England, where the big factories used to be.

Electricity substations around places such as Teesside have plenty of spare capacity. Supply is ample to feed new data centres like those in Newcastle and Blyth. The problem, Smith says, comes as you reach the Midlands and below, where the network gets thinner. Try to push too much power to the south now, he says, and the pylons would melt.

National Grid and Scottish and Southern Electricity are now working to build out the infrastructure of pylons and substations, but they are far from alone. The US, China and pretty much every country in Europe are also trying to reboot their infrastructure to serve data centres, so getting hold of the enormous transformers and other kit that is needed is not easy.

Generally, however, Smith seems confident. The collapse of heavy industry in the UK over the past 25 years has meant there should be spare generating capacity in the system. “We’re only worried about maybe 50 or 100 hours of the year in the winter peaks between four and seven o’clock when the trains are running, industry is still going and we’re all getting home and switching on our lights. So if the data centres can offer us some flexibility, perhaps saying, ‘I’ll only take that 1GW overnight’, it becomes much simpler.”

The data centres could ease their demand by installing batteries or generators to cover those three peak hours. Alternatively, they can send the data via subsea cables to data centres in the US or Europe for processing at those times. That works as long as the data is not security-sensitive. One of the main reasons companies want bigger data centres here is so they can store their UK customers’ information on British soil to comply with data protection rules.

Jensen Huang, the CEO of the chipmaker Nvidia, has shrugged off concerns of an AI bubble, reporting stronger-than-expected revenues earlier this month

AFP

Will the bubble burst?

Among investors, the biggest worry is that the building extravaganza could be getting way ahead of the likely future demand. Large language models are currently losing billions of dollars because they are investing so much more to build their AI products than customers are willing to pay for them.

All mainstream businesses claim to be using AI but nobody knows whether they will need, or be inclined to pay for, as much computing power as all these centres are being built to provide. Could AI data centres go the way of Concorde — miraculous technologically but hopeless economically?

And what if new, better technology emerges as rapidly as ChatGPT did? A taste of this came in January when a Chinese rival to ChatGPT was launched using a fraction of its computing power. On the day the program, called DeepSeek, launched, shares in US AI-related companies crashed, although they have since recovered.

After a career at EE, BT and a successful telecoms start-up, Atul Roy now invests in data centres for a London investment fund called Cordiant. While he backs only smaller sites near city centres, he shares some of the stock market’s concerns about the data centre boom of the hyperscalers. “It’s the elephant in the room,” he says.

Human beings have a habit of getting carried aloft by bubbles. Speculators and entrepreneurs wildly overbuilt the inland waterways in the “Canal Mania” of the late 1700s. The big build-out of rail networks went the same way, as companies raised fortunes on the stock market and laid thousands of miles of track to places few people wanted to go. The same thing happened a century later in 1999 after the dotcom bubble burst.

Roy, who was in the thick of the industry in the dotcom years, admits there are some similarities, but cautions against cynicism. For one thing, unlike the many over-indebted companies that collapsed when the dotcom bubble burst, the Amazons and Microsofts that are risking their money on data centres are so cash rich, they can afford to lose it.

“And besides,” he adds, “if we thought every rising trend was a boom waiting to bust, we would never invest in anything.”

Taking the longer view, there’s another reason not to be too troubled by the data centre mania. Perhaps with the exception of canals, most of the infrastructure from previous overbuilds came in handy eventually. Even after the Beeching cuts of the 1960s the Victorian rail network now forms the backbone of most train journeys, and the AI data centre hotspots of today are using fibre networks left by companies that overbuilt and lost fortunes in the dotcom bubble.

Even if demand for the data centres does not immediately live up to the industry’s wild expectations, it’s a fair bet that there will be a use for them some day.