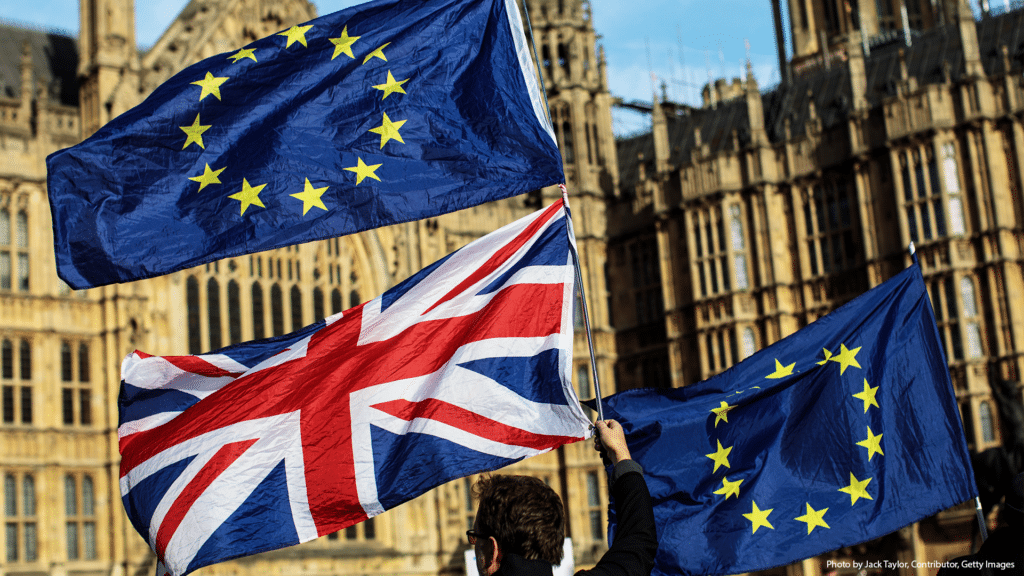

Simon Usherwood examines the impact Brexit has had on the UK and the EU, arguing it has not helped to resolve a historically ambivalent relationship with the future still looking uncertain.

Brexit exposed and deepened the UK’s long-standing uncertainty about its role in Europe and the world. Years later, there’s still no clear vision for its future relationship with the EU.

It is easy to forget that the entire Brexit process – one of the most consequential events in post-war British political history – was triggered by a miscalculation. In 2015 David Cameron, the moderate Tory who had brought his party back to electability after its longest period out of office for two centuries, won the general election and had to make good on a commitment he had made two years previously. That commitment – to hold an in-out referendum on British membership of the European Union (EU) – had been made to try to manage a noisy and rebellious faction of his party. At the time, the conditions for this seemed unlikely to be met; part of the reason that it failed to make those rebels simmer down.

The unexpected result of that referendum meant the discussion and examination of the country’s relationship with the EU and Europe more widely was a lot longer and a lot more heated than anyone would have expected in 2013.

But has all this debate produced more clarity about how the UK should deal with Europe and European integration? A moment’s recollection will suffice to provide a negative answer.

Yes, there was a vote and yes, there was a decision and yes, the UK did leave the EU in 2020, with a brace of treaties that codify both the terms of leaving and the structures for future interaction. But equally there is no more consensus about why any of this happened nor about whether it best suits the UK’s long-term interests. Indeed, the UK’s long-term interests themselves seem underdeveloped.

US Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s 1962 remark that ‘Great Britain had lost an empire and not yet found a role’ was uttered in a rather different world, one where the ignominy of Suez still burned bright, and the reconciliation of Western Europe’s competing models of integration was long away. But it captures the persistent ambivalence of the British state in its international relations, the unwillingness or inability to make a definitive and deep commitment to any one of its then ‘three circles’: Europe, the transatlantic relationship and the Empire/Commonwealth.

In 2015 that ambivalence remained, even with the UK now inside the EU, where it has made significant progress in shaping that organisation to its preferences: Margaret Thatcher’s 1988 Bruges speech, long a touchstone for eurosceptics, describing a neoliberal, free-market EU with membership stretching across the Iron Curtain. Despite this quiet success, the uncertainty about what the EU was for, and how or whether it helped or hindered the broader shape of British foreign policy remained.

The referendum did not resolve this. Neither Remain nor Leave campaigns were required to produce definitive plans for the eventuality of their winning, nor did they want to do so, since it would have meant they could not offer all things to all voters. Enough has been written about the misinformation and the disinformation elements of the campaign, but more important was that at no point was it ever intended that the referendum should produce considered and thoughtful reflection on why one choice or the other was necessary. Even the 2013 review of the balance of competences – the closest that the government came to this – was about specific policy domains, rather than the principle and purpose of EU membership.

This was only too apparent in the aftermath of the result. My strongest personal recollection of the referendum was of standing on College Green, opposite Parliament, the morning after the voting, watching countless politicians walking up for media interviews, none of them looking as if they had any sense of how to handle what would have to come next.

That stunned shock turned into the long and bitter parliamentary – and popular – arguments about ‘what Brexit meant’. By leaving things intentionally open during the campaign, activists of all stripes now fought for the opportunity to achieve their objectives. None of them succeeded in articulating a vision and getting buy-in from most quarters: Theresa May was perhaps the closest, but even before her ill-advised decision to hold another general election in 2017 it was clear that her approach was only intended to speak to that bare majority that had voted to leave.

And even in all the countless hours of parliamentary wrangling, the floating of novel ideas, workarounds, compromises, front- and back-stops, there was still no attempt to clarify the purpose of the exercise. Yes, you could forge a tiny majority in Parliament for a certain course of action, but too often it was done without checking whether an agreed UK position stood up to the EU’s own interests, let alone building up to a consensus on how relations should be.

The consequence was a deal that was sold more on being able to move on to other things (‘get Brexit done’) than on its own merits. Merits that no political party seems too enthusiastic to dwell on. Even the arrival of a Labour government in 2024, with its red lines, has struggled to say what it does want, rather than what it doesn’t. All the talk of a ‘reset’ and an ‘ambitious new relationship‘ might have produced some more friendly personal relationships in Brussels and member states, but on the eve of a UK-EU summit the absence of a strong vision for this relationship is rather conspicuous.

The long story of British awkwardness towards Europe continues to this day. The poisoning of the topic in British political debate and the fear of alienating voters in a fragmented political landscape makes it hard to imagine any government in the medium-term being willing to invest the political capital to try to overcome this and build some broader shared view of what they are trying to achieve in their relations.

In recent months we have seen the fundamentals of the international order look more uncertain than at any time since 1945 with an erratic USA and a Europe re-evaluating its system of collective security. While Starmer has put himself in the middle of the coalition of the willing on supporting Ukraine, he has also avoided any overt antagonism towards President Trump. In short, the UK is still unsure of its role, which means that European relations are liable to remain a source of tension and uncertainty for a very long time.

By Simon Usherwood, Senior Fellow, UK in a Changing Europe and Professor of Politics and International Studies, The Open University.