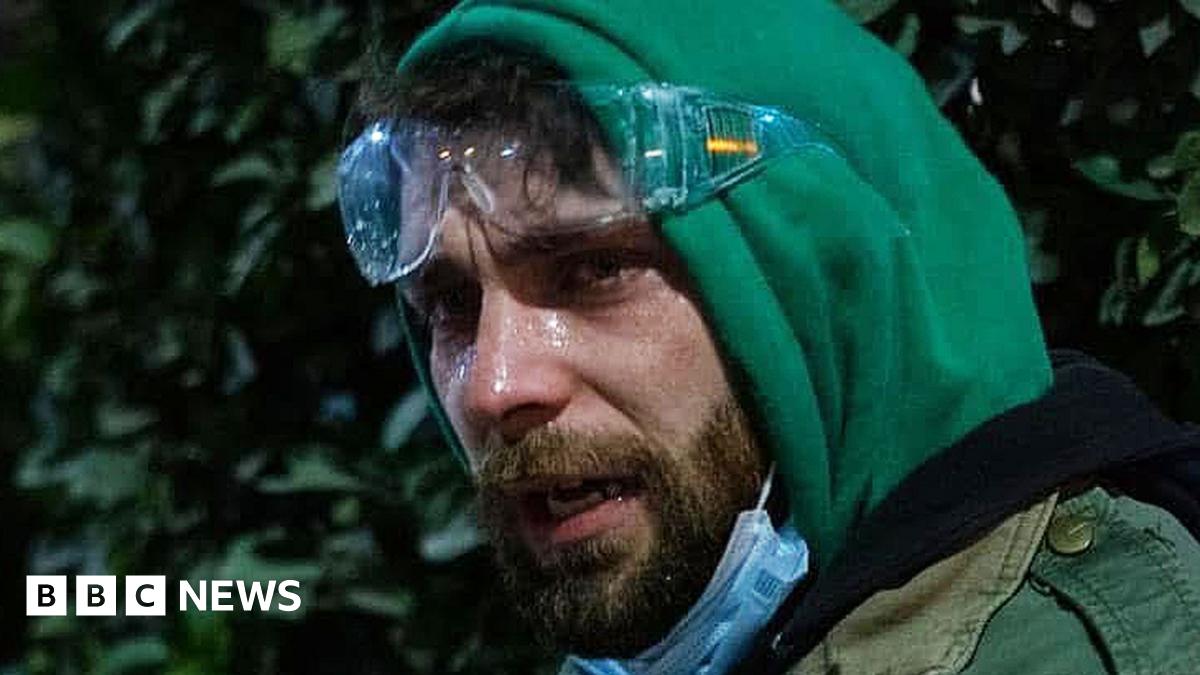

When Mr Shergelashvili was asked if the product he tested could have just been CS gas – which irritates the eyes, skin and respiratory system, but only temporarily – he said it appeared to be far stronger than that.

“I cannot name an example or compare it with anything [else],” he said, adding it was “probably 10 times” stronger than more conventional riot-control agents.

“For example, if you spill this chemical on the ground, you won’t be able to stay in that area for the next two to three days, even if you wash it off with water.”

Mr Shergelashvili does not know the name of the chemical he was asked to test.

But the BBC managed to obtain a copy of the inventory of the Special Tasks Department, dated December 2019.

We discovered it contained two unnamed chemicals. These were simply listed as “Chemical liquid UN1710” and “Chemical powder UN3439”, along with instructions for how they should be mixed.

We wanted to check whether this inventory was authentic, so we showed it to another former high-ranking police officer from the riot police who confirmed it seemed genuine. He identified the two unnamed chemicals as those likely to have been added into the water cannon.

Our next step was to work out what these chemicals were.

UN1710 was easy to identify as this is the code for trichloroethylene (TCE), a solvent that enables other chemicals to dissolve in water. We then had to work out which chemical it was helping to dissolve.

UN3439 was much harder to identify because it is an umbrella code for a whole range of industrial chemicals, all of which are hazardous.

The only one of these we found to have ever been used as a riot-control agent is bromobenzyl cyanide, also known as camite, developed by the Allies for use in World War One.

We asked Prof Christopher Holstege, a world leading toxicology and chemical weapons expert, to assess whether our evidence pointed to camite being the likely agent used.