Despite being in the middle of a bloody war, with part of its land occupied by enemy forces, Ukraine is building a unique system that could transform global conflicts – and the response to them – in the years to come.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, there have been widespread reports of sexual assaults carried out by Russian troops against civilians, including women, men and children. Survivors describe attacks ranging from rape to abduction and humiliation. These acts are not random: sexual violence has long been used as a weapon of war, intended to terrorise communities, destabilise societies, and punish those resisting occupation. As part of a systematic campaign of intimidation and control, wartime sexual violence has been seen throughout history, from Bangladesh to Bosnia, from Syria to Stalin’s Soviet Union.

From the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia to documentation of Isis’s crimes against the Yazidis, a familiar pattern emerges: atrocities occur, and justice – if it comes at all – arrives years, if not decades, later.

open image in gallery

An elderly woman cries in front of her burned house in May 2022 in Novoselivka, Ukraine (Getty)

By choosing to directly address conflict-related sexual violence while the conflict is still active, Ukraine is working to break that cycle. Developed with survivors, rather than merely for them, this approach could transform how justice is delivered in conflict situations globally.

Since the start of the war, 363 cases of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) against Ukrainian civilians have been officially documented. Those who work in conflict zones know that figure represents only the surface of a far deeper crisis. Shame, stigma and danger keep most survivors silent, while perpetrators almost always go unpunished.

What makes Ukraine different is not that these crimes are happening, but that the country is building a justice system to confront them in real time. Justice is no longer deferred until the war is over: it is being forged in the midst of it.

open image in gallery

A woman representing a rape victim leads protesters in a march in Berlin against Russian military aggression, in April 2022 (Getty)

In October 2024, Ukraine made a quiet but historic shift. Survivors of sexual violence were invited to sit alongside prosecutors and investigators from the Office of the Prosecutor General’s CRSV division, the national police, and the security service. In raw and often painful discussions, they helped to design the procedures that will govern how their cases are handled.

Working with experts, including Dr Ingrid Elliott of the UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative and the Global Rights Compliance, Ukraine’s new multi-agency task force produced detailed standard operating procedures (SOPs) to guide every CRSV investigation. The result is a system that is trauma-informed, legally rigorous, and uniquely survivor-centred.

Each survivor now works with a single focal point throughout their case to avoid re-traumatisation. All investigators undergo mandatory trauma training. Confidentiality and informed consent are embedded at every stage.

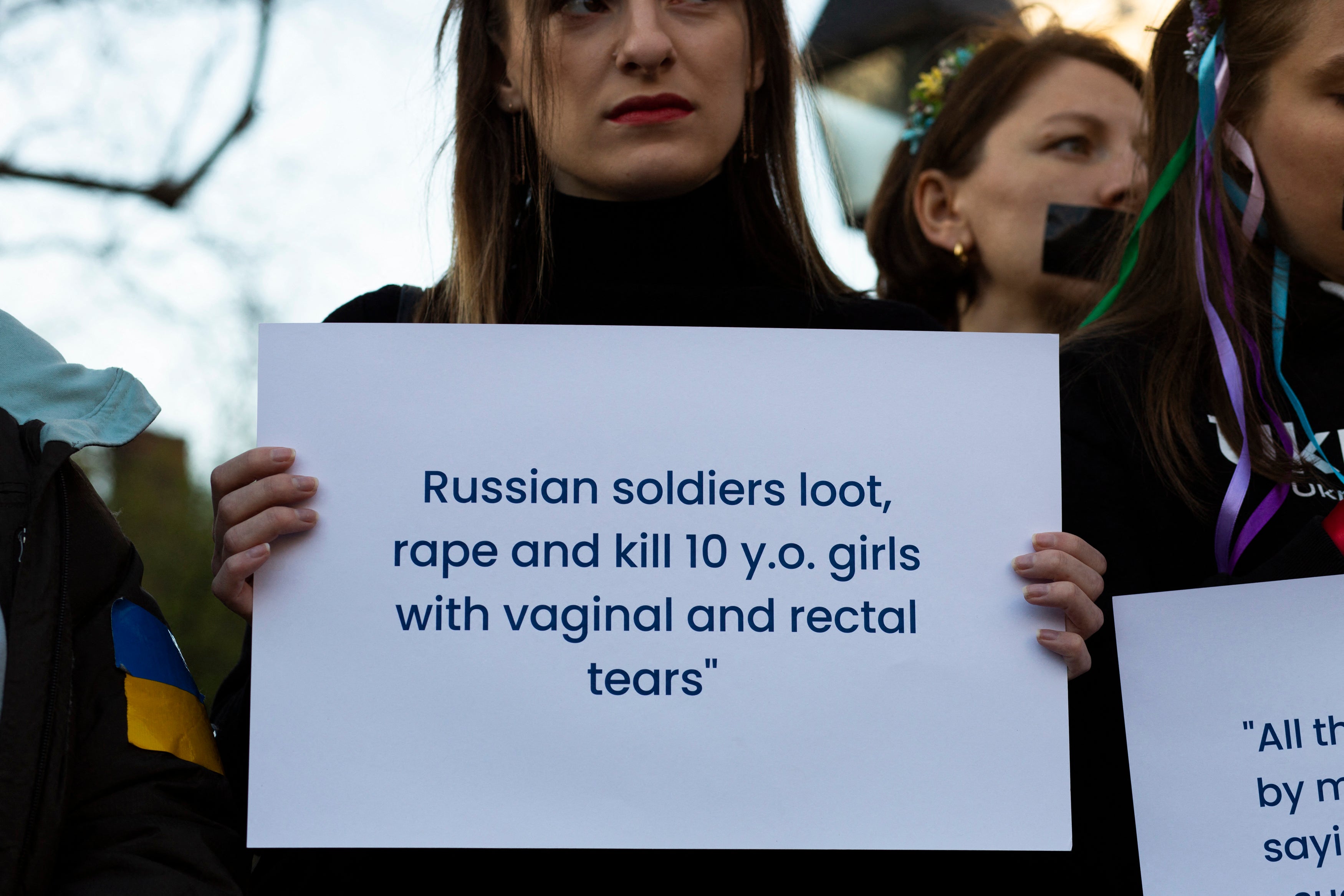

open image in gallery

A woman holds a sign denouncing sexual atrocities during a flashmob protest against sexual abuse by Russian soldiers in Ukraine, at Washington Square Park in New York City, in April 2022 (AFP/Getty)

This survivor-led model contrasts sharply with previous international efforts. When the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was created in 1994, rape was not initially included in its indictments. It took four years – and the conviction of former Rwandan mayor Jean-Paul Akayesu in 1998 – for rape to be recognised as an act of genocide. Ukraine is refusing to repeat that mistake. It is building the legal architecture for justice while the crimes are still occurring.

The framework is deeply rooted in international law. Ukraine has integrated the Istanbul Convention, the Murad Code, and EU directives into its domestic legal structure, aligning survivor protection with its Criminal Procedural Code. Crucially, it recognises male survivors and removes stigmatising language that has long deterred victims from reporting.

Perhaps most importantly, this framework is Ukrainian-owned. Many post-conflict justice systems have failed because they were imposed from outside. Ukraine’s model works because it is rooted in its own context, reflecting the country’s democratic values and its determination to pursue justice even under invasion.

open image in gallery

An elderly woman waits to get a free SIM card from a mobile operator in the town of Izyum, in the Kharkiv region, in November 2022 (AFP/Getty)

The implications extend far beyond Ukraine’s borders. Countries including Sudan, Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo could adopt aspects of this model immediately. The United Nations and the International Criminal Court now have a living blueprint for integrating justice mechanisms into humanitarian responses from the outset of a conflict. If global institutions learn from Ukraine, justice could become proactive rather than reactive – a means of protection and deterrence, not just punishment.

The Petrified Survivors sculpture – a global memorial to survivors of sexual violence in conflict – embodies the same survivor-led philosophy that underpins Ukraine’s justice reforms. Created in collaboration with more than 20 CRSV organisations, and currently on display in Berlin, every element of the sculpture was developed through years of consultation with survivor groups worldwide.

Ukrainian survivors were directly consulted, and chose the sunflower as a symbol of resilience, peace and national identity. Today, it has become a powerful emblem of international solidarity with survivors, and a fitting tribute to their courage, strength and agency.

At a time when international law is under pressure and war crimes are increasing globally, Ukraine’s example offers a new model of leadership. It proves that even amidst invasion, the rule of law can hold, and that survivors can help to design the systems that protect them. It shows that survivor-led justice can begin now, not decades later.

Ukraine has shown the world what is possible. It is now up to the world to act on it.