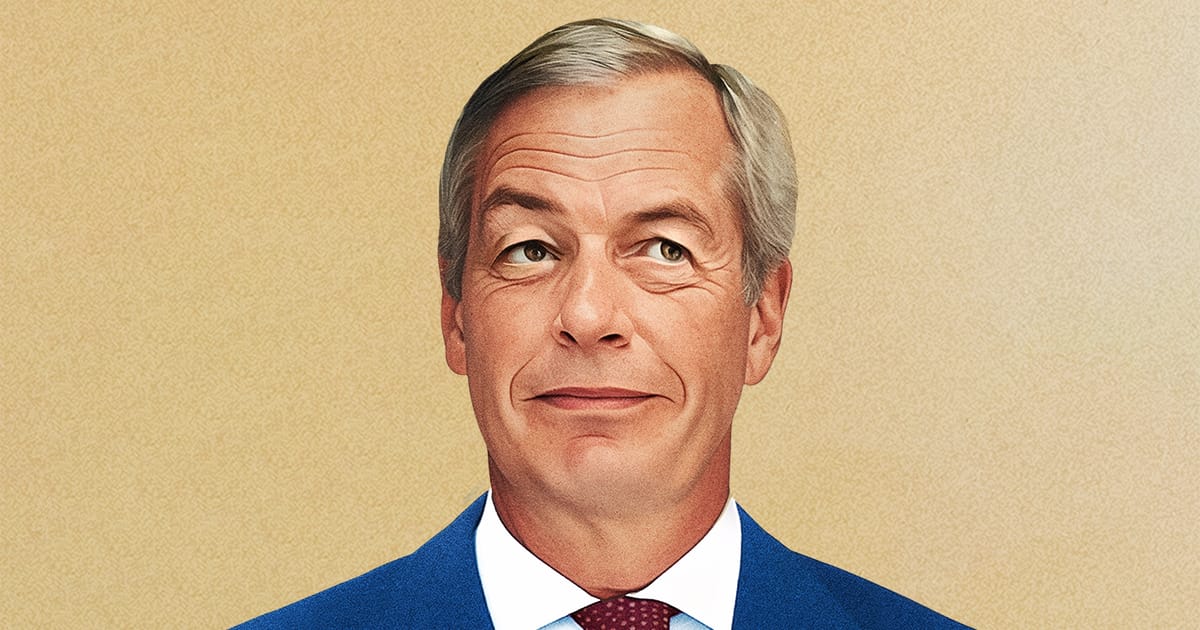

Nigel Farage has never needed the authority of an office to shape Britain’s political conversation. Nearly a decade after helping lead the United Kingdom out of the European Union, the country’s disrupter-in-chief is back at the forefront of national politics, widely seen as Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s chief opponent. With only five seats in parliament, his right-wing Reform UK party is setting the tone of British politics after a surge in the polls and a commanding performance in this spring’s local elections.

For more than two decades, Farage, 61, has thrived as Britain’s perpetual outsider — the man who remade the system without ever being accepted into it. From his early days railing against Brussels in the European Parliament to his role in the 2016 Brexit referendum, he has built his career on defiance and grievance, mixing everyman charisma with media savvy.

These days, the beer-swilling populist is looking less like a British anomaly than part of a wider European movement. Like Marine Le Pen across the English Channel, he has doubled down on anti-immigration rhetoric and moved away from his long-held Thatcherite economics toward a reindustrialization agenda aimed at the working class. And just as Le Pen has expanded beyond her base in France’s former industrial heartlands to reach broader swaths of society, Farage is breaking out of his traditional strongholds to win over younger voters and rural constituencies that once reliably backed the Conservatives.

Farage has an advantage Le Pen doesn’t: Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system gives parties the chance to clinch a landslide victory with just a third of the popular vote — roughly where Farage is polling today.

To be sure, Farage faces no shortage of challenges. If he is to make a serious play for his country’s top job, he will have to show his party — riven by infighting at local level and still struggling to root out more extreme candidates — can actually govern. He will also likely need to build up his party’s political infrastructure and expand its platform beyond immigration and opposition to cutting emissions to net zero. But the next general election doesn’t have to be held until 2029 and in the meantime, it’s largely Reform setting the agenda, with the Labour Party scrambling to parry his attacks with policies that Starmer’s critics like to describe as “Farage-lite.”

Check out the full POLITICO 28: Class of 2026, and read the Letter from the Editors for an explanation of the thinking behind the ranking.