To visit MathOverflow, an online forum for professional mathematicians, is to step into another world. Ever pondered the “quantization of symplectic vector space and choice of lagrangian subspaces”? This is your place. A fan of “polyhedral complexes and shellings”? Look no further.

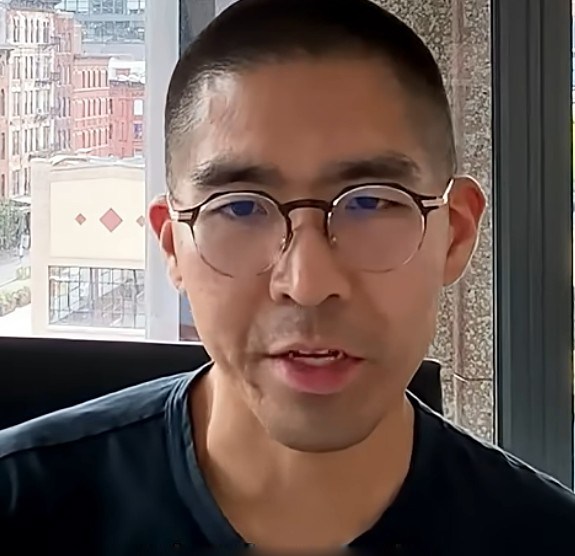

For most, this might very well be the last corner of the internet in which they would choose to spend time. Yet for Edwin Chen, it’s a happy hunting ground.

The 38-year-old billionaire founder of Surge AI, a five-year-old New York start-up, has recruited more than a million of what he claims are the brightest minds on the planet to train, to probe and to coach the world’s most capable artificial intelligence systems into becoming ever clever.

“We basically teach AI models, and then we measure how well they’re learning. We do that by bringing together the smartest people in the world,” Chen explained. “We actually have what I believe is the largest group of PhD experts in the world on a platform, teaching these models.”

People such as Oliveira Santos, 25, who spends her days crafting mind-bendingly difficult “frontier math” equations to throw at AI systems. Her first one ran to more than 40 pages. “I was planning to follow an academia kind of path where I guess my final goal was to be a professor,” she explained. “But since AI came to be, I found, ‘OK, no. I actually want to work in the industry. I think this way I feel like I can make much more of an impact on the world.’”

Much of the conversation about the AI revolution has focused on the likes of OpenAI and Google, the companies designing these powerful systems, or on the data centres and power plants being built to power them.

• Inside the power-hungry data centres taking over Britain

But there is a third leg of the stool: the millions of contractors who are, every day, all day, toiling far from the bright lights of the AI revolution, taking an hourly wage to feed data to these systems.

This unseen army, working in global locations from Lagos to London to Manila, are engaged in what amounts to an immense transfer of knowledge from humans to digital brains — one that, if Silicon Valley is to be believed, will very soon put up to half of white-collar workers out of a job.

Chen, a former AI researcher at Meta, Twitter and YouTube, has emerged as one of the key players at the heart of this booming “data labelling” industry. He has plenty of competition. Meta paid $14 billion (£10.5 billion) for half of Scale AI, Surge’s rival, this summer, while Mercor, a two-year-old start-up, recently raised $350 million from investors who valued the company at $10 billion.

Data-labelling companies may all get dropped into the same category, but they often do wildly different things. Some operate at the lower end, paying rock-bottom wages to people in the developing world to do the grunt work of labelling bits of content — this is a cat, this is a joke — so that AI can “train” on the data. Others correct the AI tools when they spit out bad answers.

Surge AI’s army specialises in “reinforcement learning through human feedback”, in which highly qualified professionals push at the outer limits of what AI systems can handle. The company pays anywhere from $20 an hour to as much as $500, depending on the labeller’s particular skills. Most of its workforce, Surge added, live in English-speaking countries in North America and Europe.

Surge AI was founded five years ago

ALAMY

Beyond the numbers, however, a labour fight is brewing over whether the contractors used by Surge AI and its ilk should be treated as employees — and thus have better pay and conditions. Glenn Danas, an attorney at the law firm Clarkson in Malibu, California, has sued Surge, Mercor and Scale AI over working conditions and wage theft.

Danas said: “In this industry, one of the unique aspects is that there are some people who are very well educated and they are being treated worse than a fast-food worker.”

His suit against Surge alleges a range of alleged infractions, including requiring unpaid training, ending projects without warning, not providing paid meal and break times, and not compensating for overtime. Surge said the suit was “without merit” and has entered into arbitration on the case.

“The problem is, we’re sort of allowing these companies to get at skills that should be very highly compensated, super cheaply,” Danas said. “The consequence will be that you’ve just sort of aided creating this thing that then won’t need you any more, and it really just didn’t pay what it should have.”

• Silicon Valley’s techies are building the AI that could replace them

Indeed, this work begs that very question: are participants not speeding their own demise tomorrow in exchange for some cash today? Oliveira Santos doesn’t look at it that way. “This is a big question that probably everyone in the field is asking themselves,” she said. She reckons, however, that AI will evolve into something of a thought partner, handling the boring parts of a job while assisting on the more knotty problems.

“I’m actually going to need AI to explore all these ideas that I didn’t have the time to explore before,” said Santos.

So just where is this frantic race leading? Chen at Surge AI is very clear: artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is a nebulous term but can be broadly understood to describe systems that are better than the sum of all humans at any cognitive work — a notion that not long ago was dismissed as the stuff of science fiction.

“We’re trying to create AGI,” Chen explained. “Not AGI that replaces us, but that makes us better in some sense, helps us explore the galaxy, helps us cure cancer, so that we can do even more.”

He started Surge in 2020 after spotting a problem that came up time and again during his years working inside the Big Tech machine. No matter what a company tried to optimise its technology for, be it clicks or retweets or comments or likes, the algorithms would always end up in the same place — optimising for low-quality clickbait: divisive posts, listicles, conspiracies.

AGI would never get built, he surmised, on cat videos and conspiracy theories. So using a few million dollars that he has amassed from his time in Big Tech, Chen launched Surge, building an automated system that scoured the globe for astrophysicists and poets and chemists, as well as intricate systems to check their work.

“We built all these algorithms to find the best people, and we have also built all these, kind of, content moderation-type systems to remove the bad people. Because we have invested so much in measurement, we can actually measure whether or not the quality is improving,” he explained. “We were basically founded because we saw that the biggest problem in reaching AGI was going to be the data.”

The company is this year expected to pull in more than $1.2 billion in sales, thanks largely to the premium it charges for its services relative to rivals less focused on “frontier” data. Nick Heiner, Surge’s head of reinforcement learning, used an analogy with golf to explain what Surge does.

To get better at golf, he explained, you could either spend, say, a million hours practising on a mini golf course, or a million hours on a professional course like California’s Pebble Beach with a coach at your elbow giving you pointers. Surge sees its work as the latter. The company is still private but is reported to be worth $30 billion, which means that Chen, who retains a 60 per cent stake, is on paper worth $18 billion.

What worries him? By who and how AI systems are being built. Chen deliberately left Silicon Valley and started his company in New York because he wanted to get out of the west coast tech “monoculture” where start-ups focus on “engagement tricks” rather than building tools that are genuinely useful.

“It’s a very ‘get rich quick’ mindset,” he said. “I worry about that because if Silicon Valley is the epicentre of AGI, and this is the mindset of the people who are building it, it’s like, ‘How does that shape your motives? How does it shape your goals?’ ”

We will soon find out.