Before jumping in on Rioja’s official anniversary, I’d like to wish all of you a joyful holiday season and thank you for supporting Dave McIntyre’s WineLine. This will be my last post for 2025, but I’ll be back in the New Year with new articles, wine recommendations and snarky commentary. I wish you a wonderful season full of good cheer and great wine!

Rioja turned 100 this year. Not as a wine region, of course — archeological evidence of wine making in Spain’s most famous vineyards dates back about 2,000 years to Roman times. In 1925, Rioja became the first of Spain’s regions designated as a Denominación de Origen (DO). Today, it is one of two regions (along with Priorat) to have the highest status as DOCa, or calificada, which translates into English as Qualified Designation of Origin (QDO).

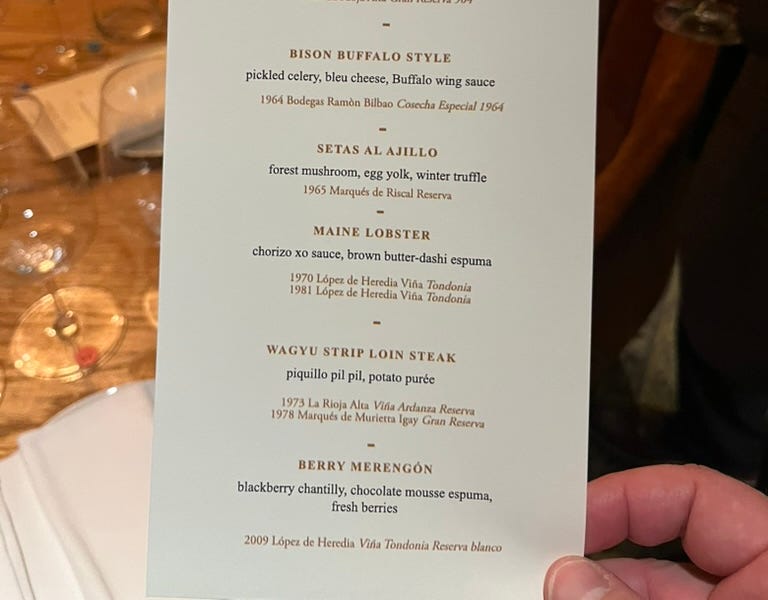

Last month, I was fortunate to attend a century celebration dinner at The Bazaar by José Andrés, featuring wines from the cellar of Alvaro Gimenez. Gimenez explained that he inherited his uncle’s wine collection and then built upon it to create a cellar of about 10,000 bottles. The menu featured 10 wines dating back to 1961, but Gimenez opened the dinner with an off-menu surprise: a bottle of CUNE Imperial 1936.

A menu of a lifetime. Photo: Me

A menu of a lifetime. Photo: Me

“You’re not only tasting Rioja tonight — you’re tasting history,” Gimenez said. “This is a unicorn wine, made during the Spanish Civil War and the start of the fascist era in Spain.” I love historical references like that. My imagination immediately flashed to Ernest Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and Saturday Night Live’s early tagline, “Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead.” This wine wasn’t dead by any means. The few sips each of us received were syrupy with flavors of toffee and dried citrus peel, reminiscent of a fine tawny port.

The rest of the wines were mostly from the 1960s and 1970s, a classic era of Rioja before the DO formalized the aging requirements we know today. A 1961 Bodegas Faustino Gran Reserva was still lively. Two vintages of La Rioja Alta Gran Reserva 904 showed quite differently. The 1964 was ruby / brick in color and Burgundian in texture, with dried fruit flavors that beguiled everyone around the table, even with a slight mustiness that evoked an ancient cellar. The 1968 was cleaner and fresher, though less entrancing.

I swooned for the 1965 Marqués de Riscal Reserva and the 1973 La Rioja Alta Viña Ardanza Reserva, with their tertiary notes of mushrooms and primal forest and acidity that somehow remained fresh throughout the decades. A 1970 López de Heredia Viña Tondonia was funky and bretty, not for everyone and definitely not for me. (A bottle of 1981 was determined to be unsound and wasn’t served.)

“This is old Rioja in its glory,” said Jordi Paronella, wine director for the José Andrés Group. “It doesn’t reflect what’s happening now.”

Classic Rioja, Paronella explained, is centered upon style, and very much a product of the winemaker’s hand in the winery. Variations occur among the three sub-regions — Rioja Alta, Rioja Alavesa and Rioja Oriental — but classic wines shared a stylistic core through the wood and bottle-aging requirements of joven, crianza, reserva and gran reserva. (These designations were traditionally used but only codified in the 1980s.)

For Gimenez, classic Rioja is fresh and long-lived because of the climate and terroir of the region and the acidity these lend to the wines. But there’s also romance.

“To open a wine from the ‘30s, ‘40s or ‘50s makes me emotional,” Gimenez told me in a video call after the dinner. “Thinking about the people who harvested the grapes and made that wine, and here we are in 2025 pulling that cork that’s been there for decades, is amazing. But the liquid has to live up to its promise, and Rioja it does.”

As much as Gimenez loves classic Rioja, he expresses excitement about newer styles emerging over the last decade or so that don’t follow the traditional aging requirements, emphasizing grapes other than Tempranillo or Garnacha and aging them in concrete, clay or stainless steel. These wines tend to be lighter and more floral, designed for early enjoyment, he said.

“The classic style is based in the cellar, with the regulations and aging requirements,” Paronella explained. “Newer Riojas are more in the vineyard, expressions of individual terroir.” He mentioned Viñedo Singular (single vineyard) as well as municipal and zone designations introduced in 2017 (all with their own “only in Rioja” regulatory restrictions), and different grape varieties that have earned official approval.

There’s also excitement around sparkling wines (officially allowed to be labeled Rioja instead of Cava as of 2017, if meeting certain requirements) and whites, with different varieties and winemaking styles.

These new styles of wines have Rioja raring to go into its new century as Spain’s premier wine region.

I asked Alvaro Gimenez and Jordi Paronella to share some of their favorite classical and new style Rioja producers.

For classical, they named:

New producers they recommend include: