I am in a plush international hotel — appropriately since my assignment is to discuss a television series whose hero, an MI6 agent, once managed a plush international hotel. “As a hotelier Jonathan was complete,” John le Carré wrote of his protagonist in the 1993 novel from which the BBC’s celebrated The Night Manager was adapted. “You did not wonder who his parents were or whether he listened to music or kept a wife and children or a dog. His gaze as he watched the door was steady as a marksman’s.”

Now, in the thriller’s long-awaited sequel, Jonathan Pine is pampered at the taxpayer’s expense in high-end hotels in Central America. Guest rather than staff, Pine maintains his inscrutability, then lies as if his life depends on it, which it does.

I am here to interview The Night Manager’s manager, the driven director of the new season that arrives on Thursday, five years after le Carré’s death. She is Georgi Banks-Davies, “early forties”, a celebrated commercials-maker who directed Billie Piper’s I Hate Suzie for Sky and was the lead director of Netflix’s Greek god riff Kaos.

“In The Night Manager, with the lead character being somebody who is constantly in disguise, hotels are definitely a place to hide in plain sight,” she says. “But they also work as a character trait. You’ll see in the second episode when Jonathan goes into a hotel, the way he talks to people, the way he takes up space, the way he decides to present himself. Hotels are great places for that because word gets around.”

Camila Morrone plays Pine’s love interest, Roxana

Broadcast in February 2016, BBC1’s original Night Manager was unexpectedly successful, attracting about ten million viewers each week, excellent reviews and prizes for its star Tom Hiddleston, its director Susanne Bier, its writer David Farr and Hugh Laurie, who played Pine’s target, the loathsome arms dealer Richard Roper. In it, Pine insinuated himself into Roper’s super-rich circle, but, the nation asked, would he expose Roper’s villainy before being found out himself? BBC management seized on the show as a prime example of the corporation bringing the UK together in a multichannel, although still barely streamer, age.

The new series begins with Pine back on the night shift and still scrutinising the more dubious clientele of hotels, but this time he is based in MI6 and watching a bank of screens displaying feeds from London fleshpots. He spots a face from Roper’s circle. Soon he has plunged through the LEDs into the real world and is in furious secret pursuit of more creatures of the night, the arms trade’s merchants of death. Pine, Banks-Davies says, is like a coffee percolator, managing the anger that boils within him by pushing it down.

“But he’s also the dormant dragon-slayer. And as soon as the puff of smoke is over the hill he has to start running. Tom and I would talk about that on set. The dragon-slayer can sit sleepily on the hill, just thinking that he’s safe, that he’s slayed the dragon. At the beginning of the first episode Roper is gone. Pine’s done it! But then what? Because who are we without purpose? And for Pine that means going back in, and by going back in I don’t mean undercover or in the service. I mean going back into oneself, looking in the mirror, accepting who you are. I mean, Pine would be in therapy for ever if he were to open up that percolator.”

Smooth on the surface, raging beneath it, Pine is the antithesis of Billie Piper’s explosive Suzie, Kaos’s impetuous deities and, perhaps, the family in which Banks-Davies grew up in Leicester and London. “It was a working-class Irish family. People are really present with their emotions and I think that’s a good thing we don’t necessaryily have so much in England.” She understands Pine, the digital night watchman. “I think about me as a child just sitting very quietly, very unobserved, very much at the back but watching everybody, watching and being fascinated.”

This time round we shall again wait to see whether Pine is rumbled by his new prey, the corrupt Colombian businessman Teddy, played by Diego Calva, or his love interest, Roxana, played by Camila Morrone. In series one Pine allowed himself to be viciously beaten up to convince Roper of his loyalty and there is a less literal version of the ritual in series two. Both sequences hint at something dark, even masochistic, in Pine and both times we cannot be sure that when he comes round he will remain in character or betray himself. This, I say to Banks-Davies, is the mechanism of much spy fiction: secretion/exposure. It is almost too easy, yet it never fails.

Olivia Colman as Pine’s former boss, Angela Burr

BBC/INK FACTORY/DES

“I think there’s the literal mechanism of the spy who is undercover and can be exposed,” she replies. “But I think there’s also a bigger one at play, in which the characters have to make peace with who they are. I’m not going to give too much away, but the three lead characters, Teddy Dos Santos, Jonathan Pine and Roxana Bolanos, all take that journey of ‘I have to understand through this who I am’.”

Hiddleston’s own journey from Eton, Cambridge and Rada to fame in the Marvel Universe as the mischievous Loki and critical respect as a Shakespearean lead was already well underway when, aged 34, he took the role of Pine. Since he was filming Kong: Skull Island when The Night Manager aired, he did not immediately appreciate its reception, he tells me.

“Months later I was invited to attend the White House correspondents’ dinner in Washington DC, where President Obama dropped the mic, and where I was introduced to then vice-president Joe Biden, who told me that they had screened The Night Manager in the White House to great excitement. That kind of thing doesn’t happen every day.”

• Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell on Marvel, Shakespeare and being mates

It seems he was always going to return for a second Night Manager. “Jonathan Pine,” he says, “is a genuinely great, complex character. Still waters run deep. I admire his extraordinary courage, and what he represents. He’s one of le Carré’s ‘lonely deciders’: people who have a strong moral compass, and — at enormous personal cost, to body and soul — choose to act on it, to do the right thing. Jonathan Pine is a solitary, soulful figure, living and working in the shadows, quietly defending our freedoms, an errant knight, aflame with moral fury. I admire his resilience, self-sacrifice and capacity for endurance.

“I’m fascinated by the tension between his internal world — turbulent, traumatised, on fire — and his external persona — immaculate, contained, controlled. He dissembles to discover the secrets of others. He seduces to betray. He lies to tell the truth.”

Diego Calva and Tom Hiddleston in a scene from The Night Manager

Hiddleston points out that when we meet Pine again that is no longer even his name. “His real identity has been erased from the record. He lives a new life under a new alias: Alex Goodwin. For Pine’s own safety, his real name, his real identity, his personal history and private pain have been buried and suppressed. His trauma has been locked deep within him, like an unexploded bomb.”

Wiring the bomb is David Farr, the British playwright, novelist and theatre director who wrote the original Night Manager and now its sequel. Fans, I tell him, will want to know what took him so long.

“I think the very simple answer is that there was never an intention to make a second season when we finished the first. It was an adaptation of a le Carré book. And nobody would go beyond le Carré. That would be sacrilegious.”

That taboo has since been lifted, and by le Carré’s sons. Nicholas Cornwell (writing under the pen name Nick Harkaway) published a Smiley novel, Karla’s Choice, last year, and it was announced this month that Stephen Cornwell is writing a new BBC series, Legacy of Spies, fusing two le Carré works, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and A Legacy of Spies. A new Night Manager, though, needed an idea that honoured not just the geopolitical anger of series one, but Pine’s psychology too. For years Farr busied himself on other projects, then the second series came to him, fittingly in the middle of the night.

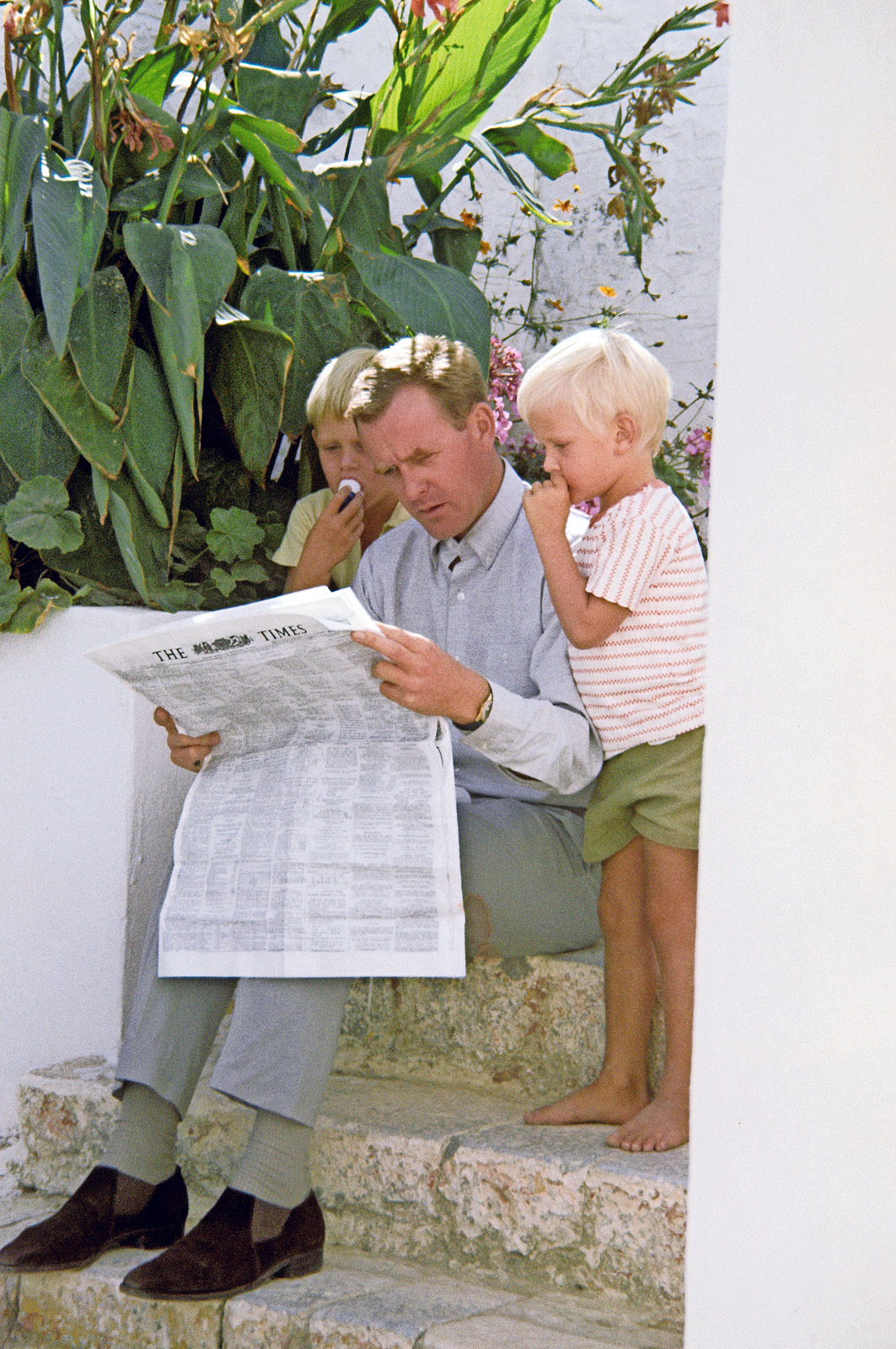

John le Carre with his sons in 1964

SAUER JEAN-CLAUDE/PARIS MATCH VIA GETTY IMAGES

“I call it the 4.30 in the morning, half-dream thing. It’s when a lot of writers and I think musicians have the best ideas. I don’t know why. The brain is somehow in an open space and weird stuff happens. Someone else can explain that better than me, but it was vividly clear and pretty comprehensive.”

He contacted Simon Cornwell, who co-heads the Ink Factory, the production company that turns his father’s oeuvre into film and television. Simon confirmed that no sequel was in development. Farr began his research in Colombia, meeting “interesting people right on the edge of the political situation” and, of course, staying in hotels Pine would appreciate. Writing the series, he missed le Carré’s enthusiasm, but was compensated by the absolute trust of his sons, “who carry the flame very consciously”.

• Le Carré’s final plot to put fraudster father centre-stage

When he met Banks-Davies, before she had been offered the directing gig, she told him the scripts were about the “perilous nature of identity”. He agreed. “Here is a younger man, Pine, who is at one level desperate to control the darkness of the world in the form of illegal arms dealing, which is why, I think, he’s called the night manager. He is patriotic and he’s honourable, but he gets lost. He gets lost in the many different identities he takes in order to infiltrate whatever operation he’s trying to bring down.

Director Georgi Banks-Davies

PHIL SHARP

“My job is to create a thriller plot that is so totally believable and gripping you almost don’t notice it. I always feel plots only become really apparent when they don’t work. When someone suddenly goes, ‘Well, I didn’t believe that’, you detach and therefore can’t do the thing Georgi wants you to do, which is to invest in the emotional narrative.”

For all this ambition, there are good reasons this Night Manager might not achieve the acclaim its predecessor enjoyed. Two of its most compulsive characters do not return: Tom Hollander’s Corky and Laurie’s Roper — although Laurie does have a cameo of sorts as Roper’s corpse. “Occasionally when we shot in London he would come down on his motorbike, looking extremely cool, just to tease Tom and be, like, ‘It’s all on you, kid,’” Banks-Davies says. Streaming has transformed linear television’s fortunes for the worse, making ratings of ten million newsworthy.

But there are even better reasons to think The Night Manager (for which a third series is already planned) will do the business again. The Oscar-winner Olivia Colman returns as Pine’s boss/surrogate mother, and Farr says Calva and Morrone are high-wattage and produce “a very hot sexual triangle” with Hiddleston, who is “brilliant”: “I think it’s the best thing he’s done.”

• Read more TV reviews, guides about what to watch and interviews

Two Januaries ago Mr Bates vs the Post Office won more than ten million viewers — and The Night Manager not only debuts on New Year’s Day, when everyone is in, but follows the first of a new series of The Traitors, whose celebrity iteration was the most-watched show of 2025. And what does Slow Horses prove if not that there is an infinite interest in spooks?

Having seen the first two episodes of The Night Manager’s return, I predict that Banks-Davies, Hiddleston and Farr will soon enough be reunited in a luxurious hotel for the first of many award ceremonies.

The Night Manager starts on BBC1 at 9.05pm on New Year’s Day