Scientists have discovered 26 previously unknown bacterial species living inside NASA’s ultra-sterile spacecraft assembly cleanrooms, challenging assumptions about the limits of microbial survival. The discovery, published in the journal Microbiome, is raising urgent questions about planetary protection standards and the potential for Earth microbes to hitch a ride to Mars.

Bacteria Thriving In The Cleanest Places On Earth

NASA cleanrooms are designed to be among the most sterile environments on Earth. Every effort is made to prevent microscopic life from contaminating spacecraft bound for other worlds, using filtration systems, UV treatments, and chemical cleaning agents. Yet despite these intense controls, researchers identified 26 resilient microbial species capable of enduring and surviving over long periods inside these cleanrooms.

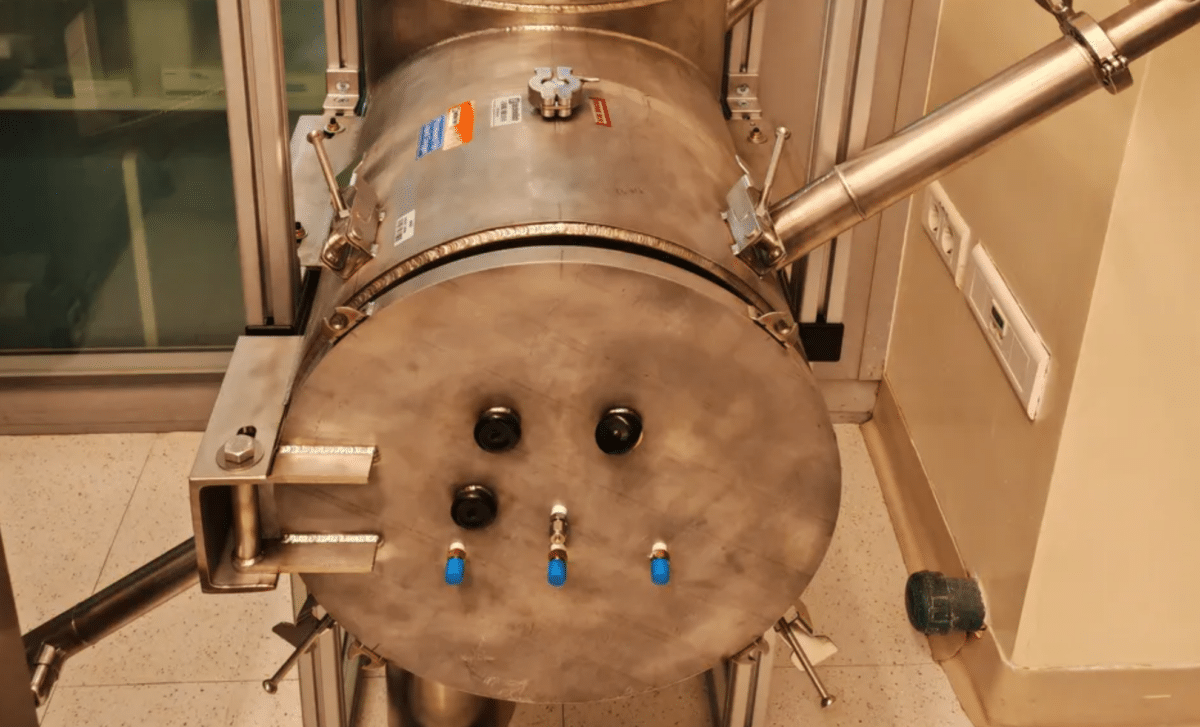

The planetary simulation chamber at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. Scientists will soon use it to recreate Mars-like and space-like conditions and test how the newly discovered microbes survive and adapt. (Image credit: Niketan Patel and Alexandre Rosado/King Abdullah University of Science and Technology)

The planetary simulation chamber at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. Scientists will soon use it to recreate Mars-like and space-like conditions and test how the newly discovered microbes survive and adapt. (Image credit: Niketan Patel and Alexandre Rosado/King Abdullah University of Science and Technology)

“It was a genuine ‘stop and re-check everything’ moment,” said Alexandre Rosado, co-author of the study and professor of bioscience at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. His statement underscores the gravity of the findings, which were based on samples collected during the assembly of NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander in 2007 and 2008.

Led by Kasthuri Venkateswaran of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the team analyzed 215 bacterial strains from cleanroom floors, some of which persisted throughout different mission phases. Back then, sequencing technology was limited. Today, thanks to advances in DNA metagenomics, the team was able to sequence and characterize these microbes in high resolution, revealing genetic traits that may help them survive deep-space travel.

Microbial Survivors With Spaceworthy Genes

The most significant implication of the study, as published in Microbiome, is that these bacteria are not random contaminants, they have evolved robust survival mechanisms. These include resistance to radiation, chemical cleaning agents, and the ability to form biofilms, enabling them to cling to cleanroom surfaces. Some even carry genes associated with DNA repair, dormancy, and spore formation, all of which are potentially beneficial traits in a space environment.

“Cleanrooms don’t contain ‘no life’,” Rosado explained. “Our results show these new species are usually rare but can be found, which fits with long-term, low-level persistence in cleanrooms.” These findings call into question whether current sterilization protocols are sufficient, especially as more missions target habitable environments like Mars’ northern polar regions or subsurface oceans on Europa.

The microbes identified in the study now represent a new frontier in planetary protection testing. They could serve as benchmark organisms for evaluating spacecraft decontamination strategies before launch, offering a unique way to validate how thoroughly a craft is sterilized.

Simulating Mars To Test Microbial Limits

To further explore how these bacteria might survive interplanetary journeys, Rosado’s team is building a planetary simulation chamber at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. Set to begin experiments in early 2026, this facility will expose the bacteria to extreme conditions modeled on those found during space travel and on Mars’ surface, including UV radiation, deep cold, carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere, and vacuum pressures.

The goal is to assess how likely these species are to survive the journey to Mars, and if they could inadvertently contaminate alien environments, a scenario that would complicate future astrobiology missions or life-detection experiments.

“This would give us a much clearer picture of which traits truly matter for planetary protection and which might have translational value in biotechnology or astrobiology,” said Rosado. The implications stretch beyond space safety, suggesting possible uses for these microbes in biotech innovation, where traits like radiation resistance and chemical tolerance could have industrial applications.

Microbial Hitchhikers And The Risk To Alien Worlds

The presence of durable life forms in NASA cleanrooms renews longstanding debates over planetary protection policies, particularly regarding contamination of pristine alien worlds. Forward contamination, where Earth microbes spread to other planets, could alter extraterrestrial ecosystems or interfere with missions designed to search for indigenous life.

This study exposes the gray area between extreme sterilization protocols and biological resilience. Even in the most sterile places on Earth, life continues to adapt. As more missions set their sights on potentially habitable destinations, such as Mars, Titan, or Enceladus, the need to understand and manage microbial persistence becomes even more urgent.

Whether these bacteria are true extremophiles capable of long-term survival beyond Earth remains to be seen. But what is clear is that the idea of “clean” in cleanrooms must be redefined, and that our assumptions about contamination need urgent scientific re-evaluation.