Heading into 2025, the consensus was that the geopolitical and economic uncertainty that had dominated 2024 would begin to recede. How wrong, once again, were the forecasters.

President Trump’s trade tariffs led to months of angst, and negotiations on a peace deal between Ukraine and Russia never really got anywhere. A ceasefire was agreed between Israel and Hamas, but the next flare-up does not seem far away.

Europe’s largest economy, Germany, continued to struggle, while France found itself engulfed in political uncertainty. In the UK, too, there has been much speculation in recent weeks about the future of Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves after an underwhelming 18 months in power.

Despite all that, global stock markets rallied to record highs throughout 2025. The FTSE 100, the top flight of the London Stock Exchange, enjoyed its best year since 2009, rising 21.5 per cent and making it five consecutive years of gains. Over the previous ten years, the index rose, on average, 2.7 per cent a year.

The FTSE 250, home to more UK-focused businesses, performed not quite as impressively, but still rose 9 per cent, its biggest annual increase since 2021 and comfortably above its ten-year average of 3.4 per cent.

The winners

Amid all the trade wars, actual wars and sluggish economic growth, investors responded by moving more of their money into gold, a safe haven in uncertain times. In fact, they moved quite a lot more: the price of an ounce of gold rose from around $2,600 in early January to over $4,300 by the end of December. For similar reasons, silver more than doubled in price to about $72.

That provided an instant boost to profits for companies that make their money digging for precious metals. Of London’s 350 biggest companies, Fresnillo, one of the world’s largest miners of gold and silver, was by far the best performer last year, rising 436.4 per cent, which led to its stock market value more than quintupling to £24 billion.

Hochschild Mining, which has gold and silver mines in Peru, Argentina and Brazil, also enjoyed a bumper 2025, during which it added 140 per cent, while the Africa-focused Endeavour Mining advanced 171.7 per cent.

The booming gold price led to a mighty 252.3 per cent rise in the value of Pan African Resources shares, enough to earn the South African miner a call-up to the FTSE 250 in December.

Much of the uncertainty that fuelled gold’s surge last year was caused by the tensions in the Middle East and the war in Ukraine, which will soon enter its fifth year.

These horrors have led, however, to a boon for the defence industry, whose hand was only strengthened by a warning in December from Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Knighton, the head of the UK armed forces, that the West needs to be ready to fight.

HMS Queen Elizabeth comes in to Portsmouth

PAUL JACOBS/PICTUREEXCLUSIVE.COM

Babcock International, the outsourcer of choice for the British military, which builds everything from armoured cars to warships and trains fighter pilots, was the pick of the defence stocks in the past year, climbing 148.4 per cent. As well as benefiting from geopolitical tensions, it has started to reap the rewards of a turnaround that began five years ago shortly after David Lockwood joined as chief executive.

Similarly, Rolls-Royce, the maker of jet engines and whose technology powers the UK’s fleet of nuclear submarines, advanced 102.3 per cent over the year. Like Babcock, its fortunes have been transformed over the past couple of years by the favourable commercial backdrop, but also by a reset under its chief executive, Tufan Erginbilgic, who joined in 2023 and, thanks to the share price, is already eyeing up a £100 million-plus bonus.

Tufan Erginbilgic, chief executive of Rolls-Royce

HOLLIE ADAMS/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES

While most forecasts for 2025 proved optimistic, the expectation that artificial intelligence would remain very much in vogue was spot on. AI-powered tools need super-fast data processing and storage to work and so data centres, now considered critical national infrastructure, were all the rage. Fitting out and plumbing in such huge, power-hungry metal sheds requires vast amounts of copper, the price of which ballooned above $12,000 a tonne for the first time.

The biggest beneficiaries of that were, unsurprisingly, the copper miners: shares in Antofagasta, which operates a handful of pits in Chile, gained 106.2 per cent during 2025, while Atalaya Mining, which mines copper in Andalusia, Spain, improved 138.2 per cent.

Another commodity player going on a tear in 2025 was AEP Plantations, the palm oil producer, which jumped 109.5 per cent. Palm oil prices fared better than some analysts had anticipated and investors bought into the decision by AEP’s revamped board to “rehabilitate” the group’s plantations. A round of share buybacks also helped to prop up the share price during the year.

From the lush forests of Indonesia to Stoke-on-Trent, the home of Goodwin, a precision engineer that makes everything from air traffic control radar systems to car tyre moulds. Demand for its niche services and products across various sectors seems only to be increasing. In December the company reported a doubling of its half-year profits to £37.2 million and it paid a special dividend — £40 million in total — to shareholders. Bosses expect the rest of its financial year to be just as busy and the shares reflected that, rising 171 per cent.

A villager making palm oil in Benin

ALAMY

Airtel Africa, the telecoms group, more than trebled in value last year, gaining 212.7 per cent. The market applauded Airtel’s half-year results in October, which showed a dramatic rise in net profits from $79 million to $376 million, aided by a combination of customer growth and cost savings. Investors also got excited about the high-growth, high-margin mobile money platform that is set to be spun off in 2026.

General corporate profitability was helped by the fall in interest rates during 2025, but there were fewer cuts from the Bank of England than economists had predicted this time last year.

Higher-for-longer interest rates were lucrative for the major banks, and a number of them saw their share prices rise handsomely during 2025. Standard Chartered was the pick of the FTSE 100 banks, rising 84.3 per cent, having made more money than most industry analysts had forecast. There are honourable mentions also for Lloyds Banking Group, up 79.3 per cent, and Barclays, which rose 77.5 per cent.

However, Close Brothers was the biggest gainer of all the listed lenders, jumping 121.2 per cent. As well as cashing in on the higher-for-longer rates, the group benefited from growing hopes that the motor finance scandal will not be as costly as many had concluded in 2024, during which its share price declined more than 70 per cent.

The losers

Accounting scandals are, thankfully for investors, not all that common, but three of last year’s biggest fallers — Wood Group, B&M and WH Smith — all suffered cock-ups in their finance departments.

In 2018 Wood Group, the oilfield engineer based in Aberdeen, was worth more than £5 billion, but it agreed this winter to be bought by Sidara, its Middle Eastern rival, for £207 million.

There was a string of nasty surprises for investors last year. An investigation into Wood’s accounts by Deloitte found “material identified weaknesses and failures” in its “financial culture, governance and controls”. The shares were then suspended for five months because it was late filing its financial statements. Before all of that, its finance chief, Arvind Balan, had to resign after it emerged that his professional qualifications had been misstated because he was not actually a chartered accountant.

Unsurprisingly the Financial Conduct Authority wanted to have a look at everything that had gone on too. Even with the takeover offer, Wood shares ended the year 63.9 per cent below where they started and are no longer in the FTSE 250.

When the British consumer is under pressure, value retailers generally outperform. Not B&M, though, whose share price declined 54 per cent. Like Wood, its finance chief departed after an accounting blunder in October led to a second profit warning in almost as many weeks. Its latest results showed a halving of pre-tax profits, and Tjeerd Jegen, who took over as chief executive in the summer, warned that he expected consumer confidence to “remain subdued for quite a while”.

It was WH Smith’s chief executive, Carl Cowling, who walked in November after the retailer found profits in its US business had been overstated by about £30 million. A review blamed “target-driven performance culture in the US” for the fiasco.

Carl Cowling stepped down as boss of WH Smith

TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER RICHARD POHLE

The company had to delay its annual results twice to give auditors more time to check over the numbers; it is trying to claw back any overpaid bonuses; and it is now the subject of an investigation by Britain’s financial regulator. Investor confidence was drained, leading to a 46.3 per cent slide in WH Smith’s shares — a worse performance than it endured even in the lockdown-hit 2020.

Another chief executive to bite the bullet last year was Andrew Rennie, who had run Domino’s Group for two years until his sudden exit in November. In 2025, what proved to be his final year in charge, Domino’s shares shed 45 per cent. There was a cut to profit guidance over summer, which Rennie blamed on weak consumer confidence, but he also struggled to win over the City with his push into the booming fried chicken market. The chatter in the industry was that there had also been a “divergence” of strategy between Rennie and the board.

Domino’s robot dog delivers pizzas on the beach

JOE PEPLER/PINPEP

Auction Technology Group has been no stranger to profit warnings in the past year or two, either. The online auctioneer took a $150 million impairment related to previous acquisitions in 2025, while the market was hardly gushing over its most recent addition, Chairish, essentially an eBay for artwork and antiques. ATG paid $85 million for it, which analysts said “looks expensive”. Investors do not seem too keen on the wider business either, and the shares fell 49.3 per cent over the past 12 months: enough to get ATG kicked out of the FTSE 250 in September.

Of the 350 biggest companies listed in London, Mobico, the company behind West Midlands buses and National Express coaches, was the worst performer in 2025, losing 70.9 per cent of its stock market value. That is unlikely to surprise many, given that Mobico has fallen in each of the past four years.

Alsa, its Spanish bus and coach division, is doing well but not enough to offset the group’s troubles with West Midlands buses, National Express and its German train business, all of which remain loss-making.

Last year was particularly painful for Mobico because of the continued rise of its German rival FlixBus, which means it has lost its near-monopoly on intercity coach travel in Britain. Still heavily indebted and with the share price toying with all-time lows, there is speculation that the Spanish Cosmen family, the founders of Alsa and Mobico’s biggest shareholders, might look at taking the group private.

The share price of another transport-related stock, Trainline, also derailed in 2025. The government’s surprise decision to freeze rail fares for the first time since the Nineties means this coming year will not be as profitable as most investors had expected, while the “ongoing unknown of Great British Railways”, as Shore Capital’s Katie Cousins describes it, was another drag on the shares, which dropped 49 per cent. The worry among investors is that if GBR builds its own “one-stop shop” ticketing app, will travellers still use Trainline?

Perhaps Trainline will seek help remaining at the forefront of consumers’ minds from its advertising agency, WPP, which also endured an annus horribilis, sliding 59.2 per cent in 2025. That was its worst showing since 1990.

The economic and geopolitical volatility, coupled with the rise of AI, means the ad market has been tough for all players, but the sense is that many of WPP’s problems have been of its own making. It dished out two profit warnings after losing lucrative contracts with the likes of Mars and Coca-Cola, cut 7,000 jobs and was booted out of the FTSE 100. Its market capitalisation sunk below £4 billion, down from £24 billion just seven years ago.

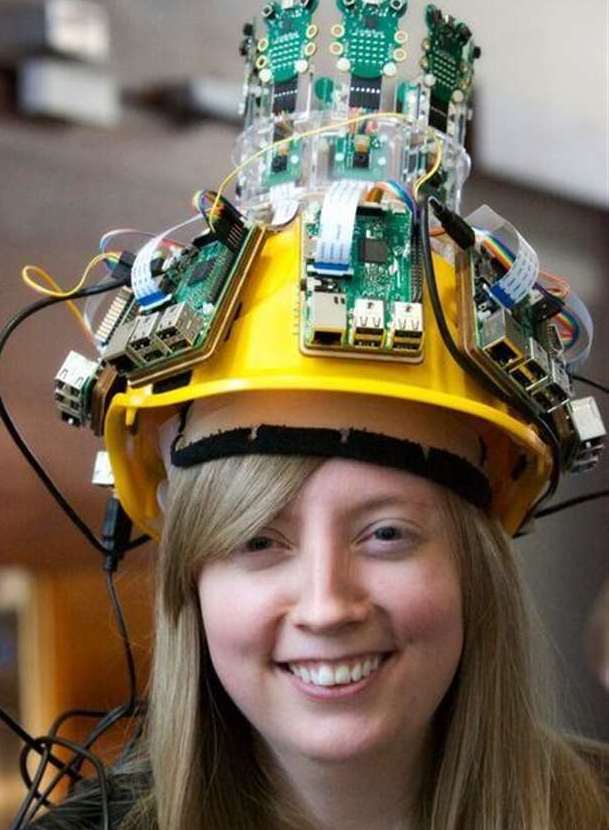

Those hoping Raspberry Pi would ride the technology wave that took Nvidia, Microsoft et al to dizzying heights were left disappointed. Shares in the company, best known for making cheap, credit-card–sized computers originally designed for teaching coding, but now used for everything from DIY electronics to robotics, drifted 52 per cent lower over the course of 2025.

Carrie Anne Philbin, director of educator support at the Raspberry Pi Foundation

Profits were pressured by “industry-wide destocking” and Raspberry Pi’s founder, Eben Upton, sold almost £2 million of his shares as soon as the first anniversary of the company’s stock market debut had passed. Sentiment was also hit by nerves related to the potential fallout from President Trump’s tariffs.

Trustpilot, the consumer reviews website, would not have made it onto this list of “losers” had it not been mauled by Grizzly Research, an American short-seller, in the run-up to Christmas.

Among other things, Grizzly accused Trustpilot of overseeing a “racket” to boost its income, artificially inflating scores for businesses that pay for memberships, while trying to attract “hyper-negative reviews” for those companies that refuse to sign up.

This was all disputed by Trustpilot, which called the allegations “categorically false” and said it was “considering all appropriate options”. Although the rebuttals — and some panic-buying of shares by the board — gave a small lift to the share price, it still fell 46.5 per cent across 2025 as a whole. Meanwhile, Grizzly is estimated to have made close to £1.5 million in barely 24 hours from its attack.