A remotely operated vehicle descended to a depth of nearly four kilometers in the Greenland Sea and identified, at 3.640 meters, the Freya’s Hydra Mounds, the deepest cold seep of gas hydrate ever recorded, altering our understanding of ecosystems, carbon, and life on the Arctic floor.

The discovery occurred on the Molloy Ridge during the expedition. Ocean Census Arctic Deep, carried out in May 2024, using the Aurora vehicle.

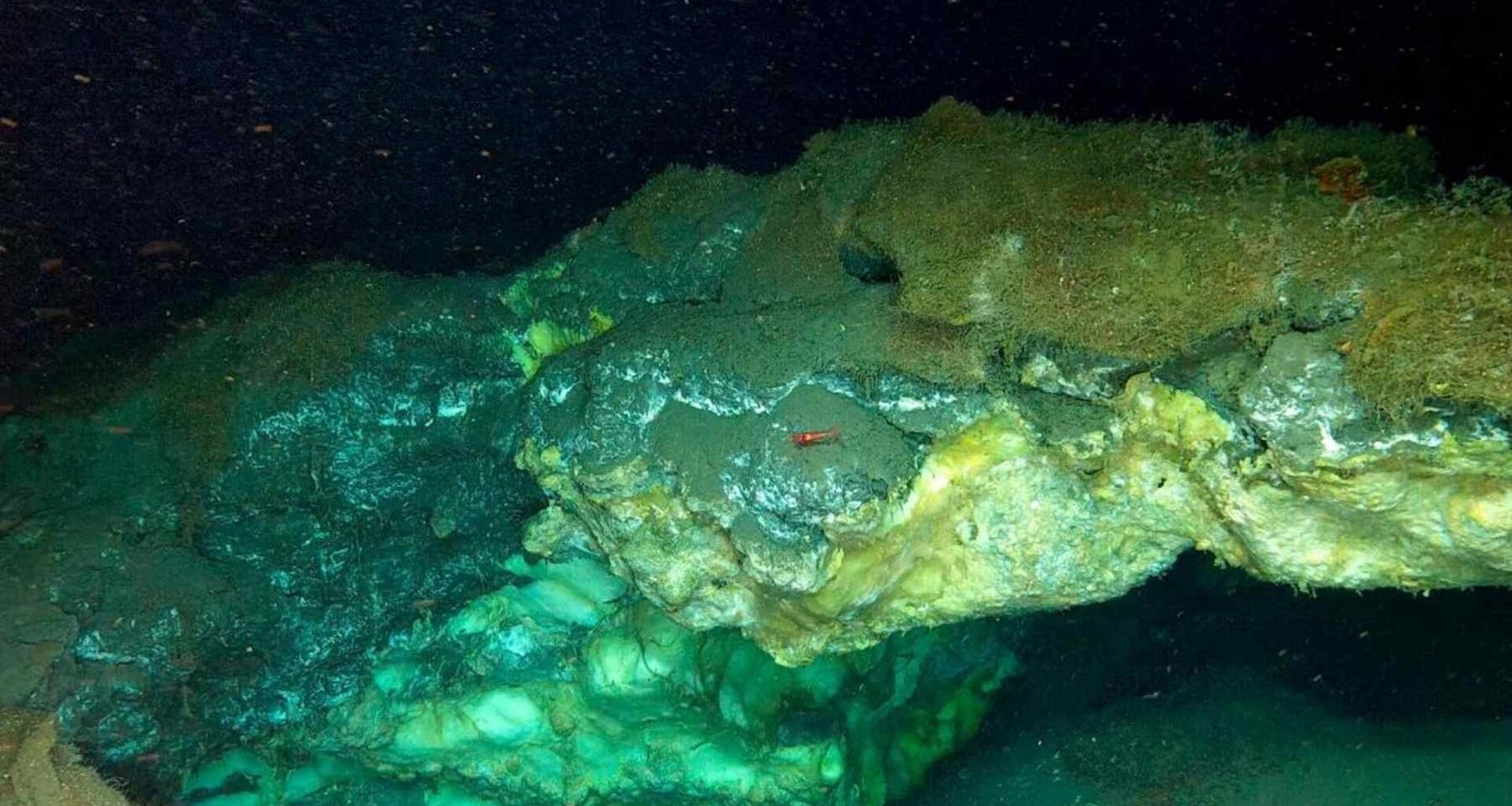

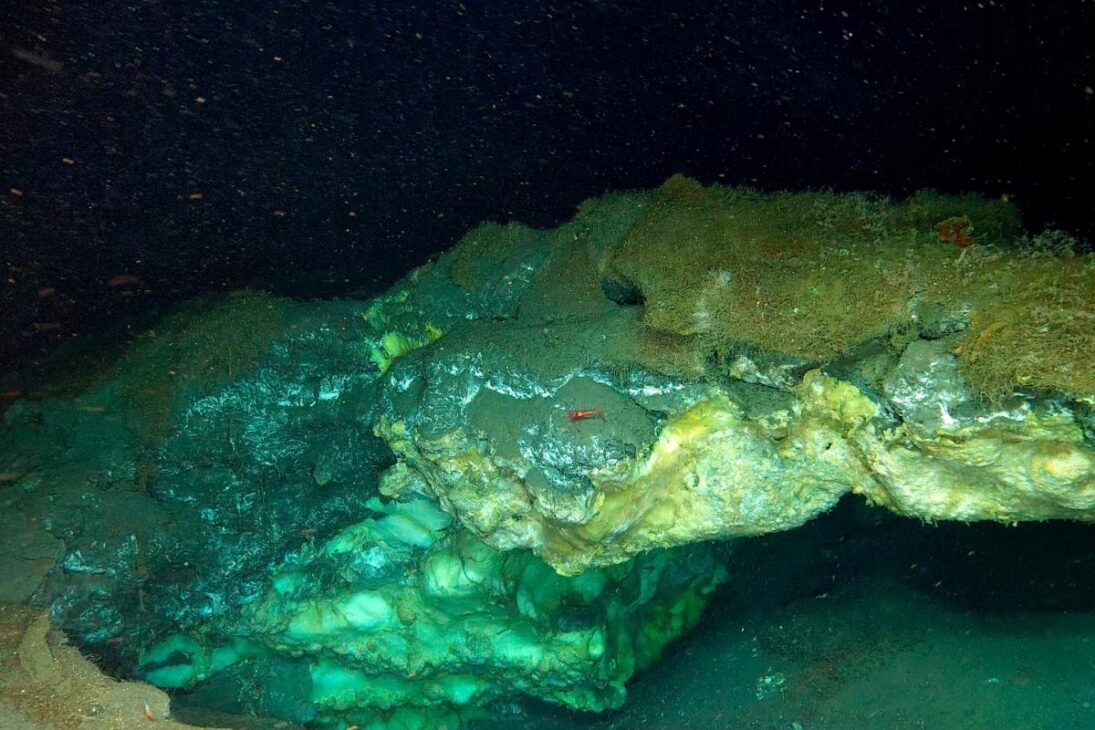

The mapping revealed a biological oasis in a region previously considered almost barren, with exposed gas hydrate deposits and associated living communities.

— ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW —

The discovery on the Molloy Ridge

Os Freya’s Hydra Mounds They were identified 3.640 meters below the surface in the Greenland Sea, in an environment of high pressure and low temperatures.

The place was described in Nature and announced by UiT, the Arctic University of Norway, after a detailed analysis of the data collected by the international team.

Observations indicate that gas hydrate deposits can form and persist at depths close to 1.800 meters, contrasting with the known pattern of cold seepage, normally recorded at less than 2.000 meters on continental slopes. In Freya, the presence of these hydrates at extreme depths expands the known limits of these systems.

Giuliana Panieri, chief scientist of the expedition, highlighted that the discovery redefines the paradigms of deep-sea Arctic ecosystems and the carbon cycle. According to her, Freya is geologically unstable and teeming with life in a part of the ocean that was previously considered almost devoid of organisms.

Photo: UiT / Ocean Census / REV Ocean

The deepest gas hydrate seepage ever recorded.

Gas hydrates, also known as fire ice, are crystalline solids that trap gases such as methane within molecular structures. waterThey remain stable only under high pressure and low temperature, conditions present on the deep ocean floor.

Global scientific estimates indicate that these hydrates store between 500 and 2.500 gigatons of carbon, making them one of the largest hidden reservoirs of a potent greenhouse gas. In Freya, these hydrates emerge directly from the seabed, forming visible structures.

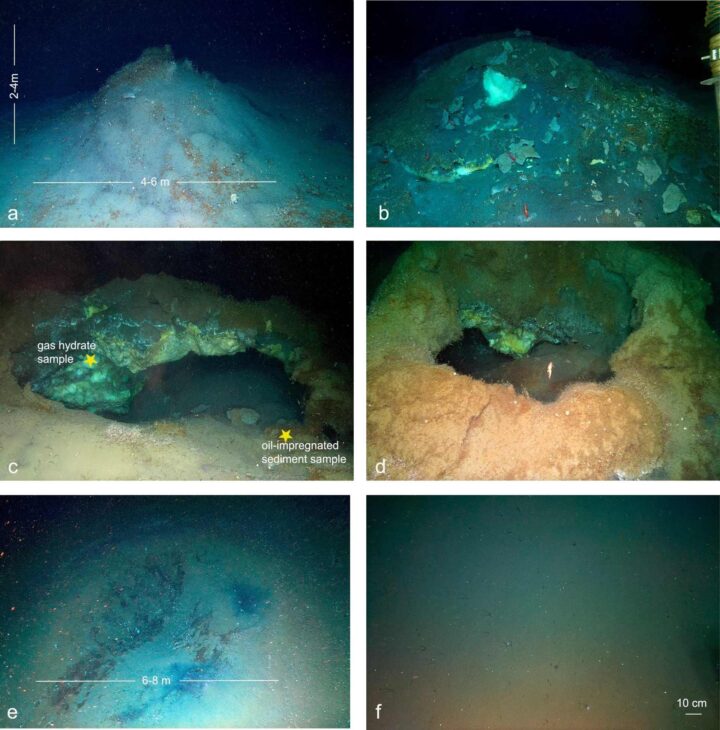

Aurora’s cameras identified three conical mounds, with diameters between four and six meters and up to four meters high. In addition to these, collapse craters and low ridges were observed, distributed over an area of approximately 100 by 100 meters, forming a complex geomorphological field.

Onboard sonar tracked methane-rich plumes rising more than 3.300 meters through the water column, reaching about 300 meters from the surface. These plumes are among the largest gas flares ever documented in deep marine environments.

Chemical composition and origin of gases

Chemical analyses indicate that the hydrates contain a gaseous mixture dominated by methane, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the total identified. The remainder includes ethane, propane, and butane, pointing to the presence of thermogenic hydrocarbons.

This composition suggests that the gases originate from Miocene-era sediments located deeper within the Earth’s crust.

The ascent of these compounds to the seabed highlights the connection between deep geological processes and the chemical dynamics observed in Freya.

The results reinforce the idea that the system is active and unstable, with continuous release of gases and direct interaction with deep ocean water, influencing both the local geology and the associated ecosystems.

To: Martin Hartley / The Nippon Foundation–Nekton Ocean Census.

Life at the extreme edge of the ocean.

Despite the total absence of sunlight, more than twenty types of fauna have been recorded in and around the mounds. The basis of this community lies in chemosynthesis, not photosynthesis, using chemical reactions as a source of energy.

Among the organisms observed, dense forests of Sclerolinum stand out, formed by siboglinid tube worms that harbor bacteria capable of using methane and sulfide as fuel. These worms structure the habitat and support other forms of life.

Snails, amphipods, polychaetes, and small crustaceans circulate among the tubes, feeding on chemosynthetic microbes or other organisms.

This food web is maintained in waters with temperatures around -0,63 degrees Celsius, slightly below the normal freezing point of seawater.

For researchers who track the biodiversity of the deep sea, the finding reinforces the idea that Arctic basins, often labeled as empty on global maps, actually harbor complex communities linked to the underlying geology, contradicting long-held perceptions of the sterility of these environments.

Ecological connections with other deep systems

Comparisons between Freya and the Jøtul hydrothermal vent field, located at a depth of approximately 3.020 meters in the Knipovich Ridge, revealed significant similarities. At the animal family level, the community associated with the methane vent more closely resembles that of this hydrothermal system than shallower, colder vents in the Arctic.

This proximity suggests strong ecological links between distinct but geographically close deep habitats. Jonathan Copley, responsible for the biogeographical analysis, believes that Freya may be just the first of several similar systems yet to be identified in the region.

According to him, the organisms that inhabit these environments can play a vital role in the overall biodiversity of the Arctic Deep, functioning like ecological nodes in a fragmented and extreme setting.

Mineral exploration and political decisions

The Freya Mounds are located in an area of the Arctic seabed between Jan Mayen and Svalbard that was opened by Norway for marine mineral exploration in early 2024. At that time, companies were invited to nominate blocks for future mining licenses aimed at obtaining metals used in batteries, wind turbines, and other technologies.

Following public pressure and legal challenges, the country agreed not to issue new deep-water mining licenses in the Arctic. It also decided to suspend public funding for seabed mineral mapping until at least the end of 2029.

United Nations experts deemed the measure consistent with the precautionary principle and with obligations to protect the ocean and the climate system. For the scientists involved in Freya, this pause is crucial to ensuring the integrity of the site.

Copley describes these ecosystems as island-like habitats, vulnerable to intense industrial activity. Panieri defines the Freya hills as living geological formations, sensitive to tectonics, deep heat flow, and changes in the waters of the Fram Strait.

Global relevance of the finding

Although located four kilometers deep, the Freya system integrates the global carbon cycle through the methane stored in its carbohydrates. The associated food webs are also part of the network protecting ocean biodiversity.

The site offers an ultra-deep natural laboratory for observing how methane moves through the water column and how cold seep ecosystems respond to the gradual warming of the Arctic Ocean. Future decisions on deep-sea mining and climate policies will directly influence the fate of this newly documented oasis.

The study detailing the discovery was published on the UI website. Arctic University of Norway, solidifying Freya as one of the most profound and relevant findings ever recorded in the marine Arctic.