For more than 70 years, what were believed to be mammoth fossils were housed in the archives of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. These remains, discovered in the 1950s in the gold mines of Dome Creek, near Fairbanks, were assumed to be relics of the Ice Age giants that once roamed the earth. However, recent analysis has revealed that these bones, instead of belonging to long-extinct mammoths, actually came from two ancient whales. This surprising discovery was detailed in a recent study published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, which sheds light on the mix-up and the scientific process that led to the revelation.

The Initial Discovery and Mistaken Identity

In the 1950s, fossils were discovered in Dome Creek, a site located in Alaska’s interior, roughly 250 miles from the nearest coastline. The bones were initially labeled as mammoth fossils, a reasonable assumption considering the prevalence of mammoth remains across North America. The fossils were kept in the archives of the University of Alaska Museum of the North for decades, where they remained relatively undisturbed until the museum’s Adopt-a-Mammoth program allowed the public to sponsor tests on various fossil specimens.

The excitement surrounding these remains grew when radiocarbon dating revealed an unexpected result. According to the carbon analysis, the bones were between 1,854 and 2,731 years old, far younger than what would be expected for mammoth remains, which are believed to have gone extinct about 13,000 years ago. This raised significant questions within the scientific community and prompted further investigation into the identity of the fossils. As the researchers note:

“Our investigations culminated with DNA analyses of the two specimens, which secured identities as whales and corroborated our stable isotope findings.”

The Role of Isotope Analysis in Uncovering the Truth

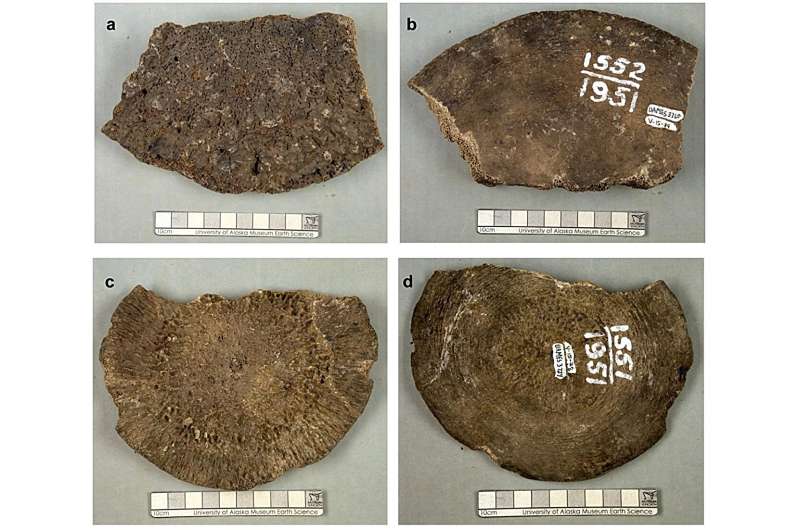

In order to solve the mystery of the fossils’ identity, the research team, led by Matthew Wooller of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, first performed a stable isotope analysis on the two fossilized disks. These disks, originating from the animals’ spines, provided essential clues about the organisms’ diets and environments. The stable isotope ratios, particularly nitrogen and carbon, were markedly different from those found in terrestrial mammals, such as mammoths. Instead, the isotopic signature resembled that of marine creatures, suggesting that the remains belonged to ocean-dwelling animals rather than land mammals.

This finding was a key breakthrough. Stable isotope analysis has long been used by paleontologists to understand the ecological niches of ancient organisms, and in this case, it pointed unmistakably toward marine life. While the isotopic data was compelling, it wasn’t enough to definitively identify the species of the fossils. That’s where DNA analysis came into play. The research team sequenced the DNA found in the fossils, confirming that these bones did not belong to any mammoth at all but to two different species of whales: a minke whale and a North Pacific right whale.

DNA Analysis and the Confirmation of Marine Origins

DNA analysis played a critical role in this discovery. After the isotope analysis had pointed researchers in the right direction, they turned to genetic sequencing to further confirm the identity of the fossils. The DNA extracted from the bones revealed that the specimens were indeed whales, not land mammals. As the researchers note:

“Our investigations culminated with DNA analyses of the two specimens, which secured identities as whales and corroborated our stable isotope findings.”

This analysis provided the final piece of the puzzle, confirming that the remains were not only marine in origin but also linked to species of whales that were likely present in the region thousands of years ago.

The confirmation of these ancient whale species has significant implications for our understanding of past marine ecosystems and the history of marine mammals. It also underscores the importance of using multiple scientific techniques, such as isotope analysis and DNA sequencing, to unravel the mysteries of ancient life. This case exemplifies how new methods can be used to reinterpret old specimens and challenge assumptions made by previous generations of scientists.

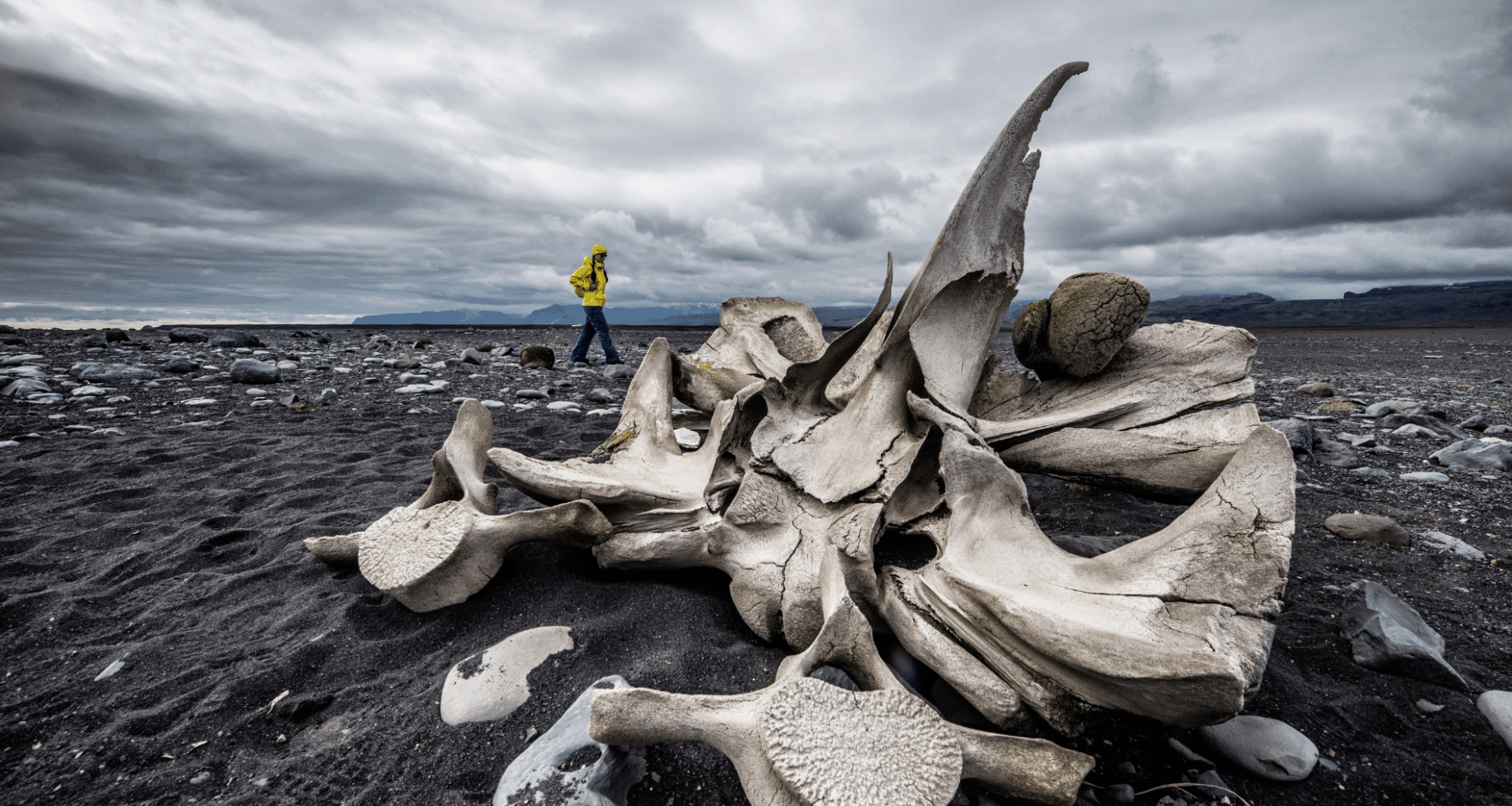

Reconsidering the Fossils’ Location: How Did Whales End Up Inland?

One of the most intriguing aspects of the discovery, published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, is the location where the fossils were found. Dome Creek, situated deep in Alaska’s interior, is far removed from the ocean, raising the question of how marine creatures ended up so far from the coast. The research team proposed several theories to explain this geographical anomaly. One possibility is that the whales swam up the Yukon and Tanana rivers, which flow through the region, before dying and being buried. However, this idea is seen as unlikely for the North Pacific right whale, as this species feeds on plankton, which would not be found in river systems.

Another theory suggests that the bones could have been brought inland by ancient humans. The idea is that early people may have used the bones for tools or traded them, carrying them from the coast to the interior. This theory is plausible, given the trade networks that existed among Indigenous peoples in ancient times. Yet, the simplest explanation may be a clerical error. When the fossils were first collected, they may have been mistakenly labeled as coming from the Fairbanks area, instead of the coastal regions, which could have led to their misplacement in the museum’s archives.