Nearly 200 years ago, the physicists Claude-Louis Navier and George Gabriel Stokes put the finishing touches on a set of equations that describe how fluids swirl. And for nearly 200 years, the Navier-Stokes equations have served as an unimpeachable theory of how fluids in the real world behave — from ocean currents threading their way between the continents to air wrapping around an aircraft’s wings.

Nevertheless, many mathematicians suspect that glitches hide deep within the equations. They have a hunch that in certain situations, the theory fails. In these cases, the equations will predict a fluid moving in some unphysical, incomprehensible way — spinning into an impossibly fast vortex, for instance, or instantly reversing its flow. Some quantity in the equations will grow infinitely large, or “blow up,” as mathematicians put it.

Despite immense effort, no one has been able to come up with a situation where the Navier-Stokes equations falter. Doing so — or, alternatively, proving that the equations never blow up — would come with a $1 million reward. And so, as a prelude to solving the Navier-Stokes problem, mathematicians have searched for blowups (also called singularities) in an assortment of simplified fluid equations, such as those that operate in only one dimension.

They’ve found them. But essentially all the singularities they’ve identified have been “stable,” meaning that they can form in many possible ways. In the most realistic fluid theories, including Navier-Stokes, blowups (if they exist) are likely to be far more delicate, occurring in an unimaginably precise way. These “unstable” blowups have been nearly impossible to find, the ultimate needles in the haystack.

In these realistic theories, “a lot of people believe that there are singularities, but that they are unstable, so we never see them,” said Charlie Fefferman, a mathematician at Princeton University who formulated the million-dollar Navier-Stokes challenge.

Now one group of mathematicians has developed a way of training machines to spot these phantom glitches. In a preprint posted in September, they reexamined simpler fluid equations already known to host a stable singularity. There, they found additional potential blowup scenarios — including unstable ones. It was the first time a possible unstable singularity was uncovered in a fluid of more than one dimension.

The team went on to discover an assortment of unstable singularity candidates in several other fluid equations as well. They have not found any million-dollar singularities. And they still need to rigorously prove that the ones they have found do indeed blow up. But their success in uncovering potential unstable singularities in simple models raises hopes that it will also be possible to find unstable blowups in higher-stakes scenarios.

“The idea of an unstable singularity no longer prevents the discovery of the singularity,” said Fefferman, who was not involved in the new research.

Singularity Hunting

A solution to the Navier-Stokes equations captures a slice of eternity. Solving the equations for some initial state of the fluid will tell you the fluid’s velocity at each point in space and at every moment in time. In one simple solution, a fluid might start calm and remain calm forever. In a more complicated setup, gentle currents might merge into whirlpools and eddies. The great mystery is whether every solution — every single possible fluid history that satisfies the Navier-Stokes equations — makes sense everywhere and always.

But tackling the Navier-Stokes equations for fluids in three dimensions is unspeakably difficult, so mathematicians have started with easier versions of the problem. For instance, the Euler equations assume that fluids flow with no internal friction, or viscosity. Energy doesn’t dissipate in these frictionless fluids, so they should blow up more easily than viscous ones.

But even in this simpler scenario, finding a blowup solution is hard. Fluid equations are generally too complicated to solve directly with pencil and paper. So a common approach is to use a computer to simulate the fluid’s motion and get an approximate sense of the conditions that seem to produce a blowup. If you can narrowly identify the blowup-producing conditions, you might be able to use that knowledge to rigorously prove that a blowup truly exists.

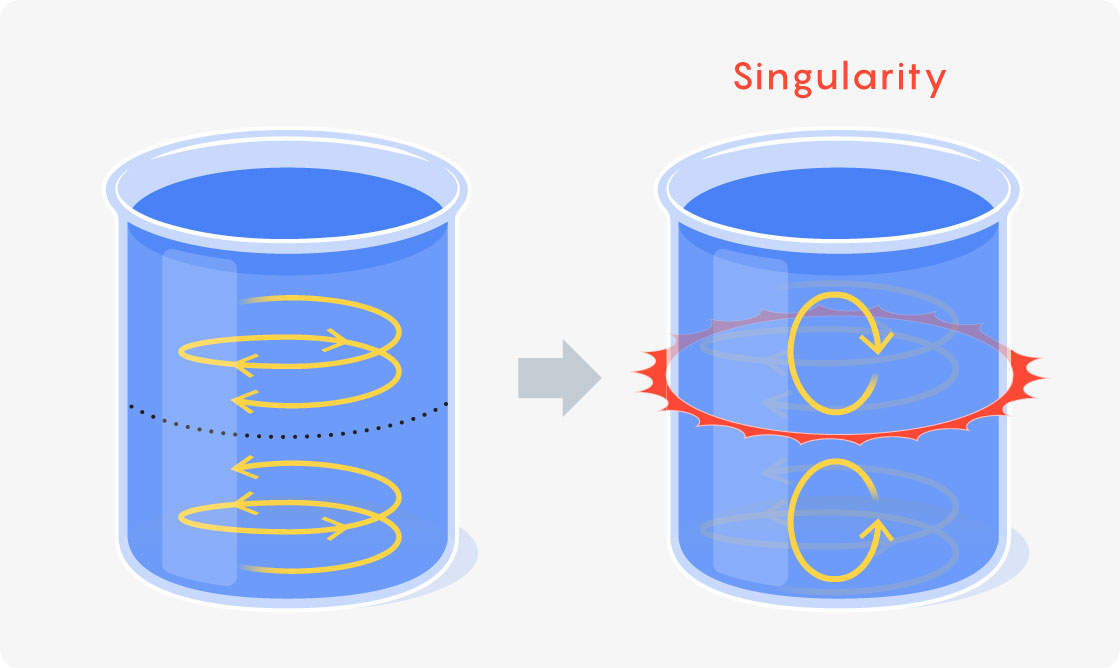

That’s the approach that Thomas Hou and Guo Luo took in 2013, when they simulated a digital liquid in a can. They set the top half of the liquid spinning in one direction and the bottom half in the other, then evolved this scenario through time using the Euler equations. Eventually, at points where the opposing flows met along the can’s boundary, the vorticity (a measure of how much the liquid spins around a point) got big — bigger than their computer could handle.

Mark Belan/Quanta Magazine

This was a hint that a similar set of conditions would lead to a blowup. But it was not a guarantee. “The graveyards are strewn with alleged singular solutions of 3D Euler,” Fefferman said.

It took Hou and another collaborator, Jiajie Chen, nearly a decade to remove the “alleged.” In 2022, they used a computer to prove that the singularity candidate implied the existence of a true singularity. It was a landmark proof, and it got mathematicians hungry to push the frontier even further.

The research depended on computer simulations, which meant that tiny adjustments to the initial state of the digital fluid (or any digital rounding errors) wouldn’t affect the fluid’s fate. A singularity would still occur at the can’s boundary even if things played out a little bit differently.

Because of this, the singularity was stable. But a singularity need not be stable. A blowup might occur only when the fluid is set up in the most delicate of ways. In such a case, any adjustment to that initial arrangement, no matter how small, would prevent the fluid from blowing up.

Many mathematicians conjecture that if singularities do lurk in more realistic fluid equations, they’ll be unstable like this, springing up without warning.

They’ll also be far harder to find.

Going Finite

It’s essentially impossible to track down an unstable singularity candidate with a computer simulation. First you’d need a cosmic stroke of luck to land on exactly the right initial configuration for your fluid — akin to trying to balance a pen perfectly on its tip, said Tristan Buckmaster, a mathematician at New York University. Then, to keep it balanced, you’d also have to evolve the fluid flawlessly from one moment to the next, since even the smallest deviation will tip it onto a path that doesn’t blow up.

Computers aren’t capable of infinite precision. They’ll inevitably introduce numerical errors that, though tiny, will stop the unstable singularity from forming. “It’s like the wind blowing on your pen,” Buckmaster said.