By Joy E. Glenn

JANUARY in Spain is magical for children.

The Cabalgata de Reyes is one of the most anticipated events of the year. Candy flying through the air, music filling the streets, children’s faces lit with excitement as they wait for the Three Kings to pass by.

My children love it, just like most kids do. It is joy. It is tradition. It is childhood.

And yet, every year, there is a moment of discomfort we cannot ignore.

When the float of Baltazar approaches, and we see faces painted black and brown, exaggerated lips, costumes that turn blackness into something worn for the afternoon, the joy pauses.

My children notice. They ask questions. And I am left navigating a moment that should never be theirs to carry.

This article is not written to attack or shame. It is written to explain because many Spaniards genuinely do not understand why this is painful.

Junta president Juanma Moreno (left) appeared in blackface for a Three Kings parade in Sevilla on January 5. Credit: X/@JuanMa_Moreno

Junta president Juanma Moreno (left) appeared in blackface for a Three Kings parade in Sevilla on January 5. Credit: X/@JuanMa_Moreno

That lack of understanding is not always rooted in hatred, but in ignorance in its truest sense: a lack of knowledge. And knowledge matters.

I understand that portraying King Baltazar is considered an honour in Spain. Many people feel proud to play him. They believe they are paying homage, not mocking.

But intent does not erase impact. For black people, seeing non-black people paint their faces black, even ‘out of respect’, is painful because our skin is not a costume.

We do not get to take it off at the end of the parade. We live in this skin every day; through admiration, yes, but also through discrimination, judgment, and sometimes dehumanization.

What is worn for celebration by some is lived as reality by others.

Years ago, my son played Zeus in a school performance. He dressed as Zeus. He embodied the character. But he did not paint his face white because that would have been unnecessary and inappropriate.

Black people have never needed to paint our faces to portray white characters. We understand that race is not a costume.

So, when people darken their skin, exaggerate lips, and perform blackness visually, it raises a painful question: Is this how you see us?

Especially when, paradoxically, black features are so often copied and commodified – fuller lips, curvier bodies, black music, black style – while black people themselves are still disrespected, excluded, or ignored.

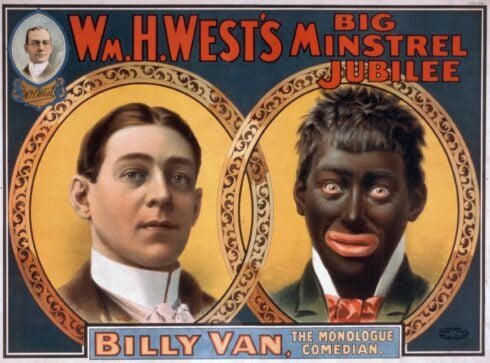

In the United States, blackface has a long and deeply racist history.

It originated in minstrel shows, where white performers painted their faces black to mock, dehumanise, and caricature enslaved Africans and their descendants.

These performances reinforced harmful stereotypes that justified violence, exclusion, and systemic racism.

READ MORE: Malaga’s ‘DANA migrant hero’ will play Balthazar in the city’s Three Kings’ parade

The racist practice of blackface originated in minstrel shows in the USA. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The racist practice of blackface originated in minstrel shows in the USA. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

That history matters because symbols carry memory, even across borders.

While Spain has a different historical context, the image itself still lands on black people with the weight of that global history. Pain does not stop at national lines.

Spain today is not the Spain of the past. It is increasingly diverse. There are thousands of black and bi-racial children growing up here. Children with one Spanish parent and one black parent, children who are fully Spanish and fully black.

What are they meant to feel when they see their skin colour painted onto someone else’s face for entertainment?

My children love the Cabalgata. I do not want to take that joy away from them. But every year, we experience that moment of quiet discomfort, an unspoken embarrassment when tradition clashes with dignity. Children notice more than we think.

Let me be clear: Black people are proud to be black. We love our skin. Our hair. Our culture. Our history. Our resilience. Even with all the pain the world has placed on us, I would not trade my blackness for anything. Not even for ease.

Black families celebrating the Cabalgata experience a moment of quiet discomfort when the floats pass. Credit: Joy E. Glenn

Black families celebrating the Cabalgata experience a moment of quiet discomfort when the floats pass. Credit: Joy E. Glenn

What we are asking for is not erasure of tradition but evolution with respect. We are not asking to be pitied. We are asking to be seen as human.

In fact, as I write this, there’s an active petition circulating, calling for an end to blackface in Spain. It’s not just a personal plea; it’s a conversation many are having, and it shows that more and more people understand it’s time for change.

Spain can certainly continue traditions unchanged. That is a choice. But once perspective is shared, once voices are heard, once black families explain how this feels, then ignorance is no longer an excuse.

Spain is becoming more diverse. That is not a threat. It is, in fact a beautiful reality. And reality invites reflection.

This article is simply an invitation to listen. Because respect does not erase tradition but it strengthens it.

Joy E. Glenn is an author, creative writer, screenwriter and U.S. Air Force veteran from Florida, USA who lives in southern Spain. She is the mother of three children and author of the book, ‘Spain: Through the eyes of a Black American woman’.

Click here to read more Spain News from The Olive Press.