BUENOS AIRES, Jan. 13 (UPI) — Argentina has repaid $2.5 billion to the U.S. Treasury, returning funds it received in October under a $20 billion currency swap agreement, authorities from both countries said.

Argentina’s central bank said in a statement the repayment was completed Friday, using resources from multilateral financial institutions, without naming them.

Some analysts said part of the funds may have come from the Bank for International Settlements, based in Basel, Switzerland, though there was no official confirmation.

Argentina only used $2.5 billion from the swap because the credit line functioned as an emergency backstop, not as a loan that had to be fully drawn. The country took only what was necessary at a specific moment to cover dollar shortages and reassure the markets.

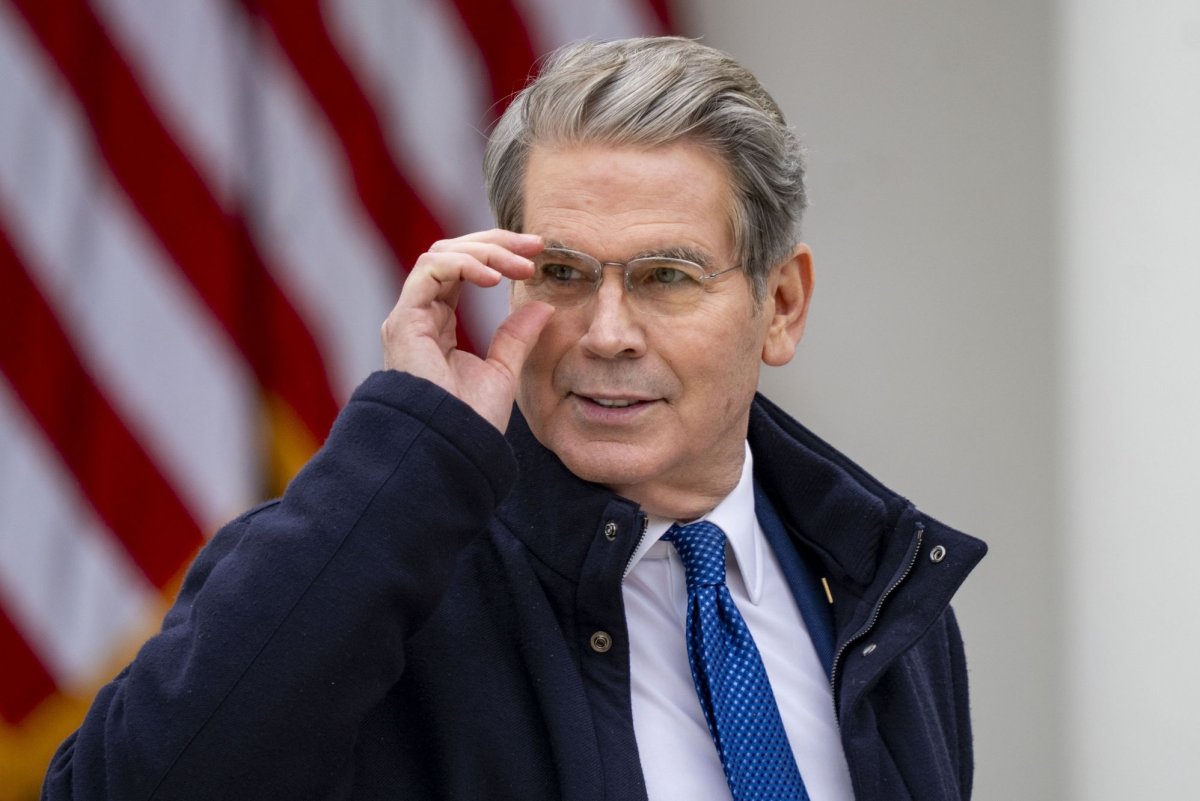

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent confirmed the repayment in a post on X.

“Stabilizing a strong ally and generating tens of millions in gains for Americans is a major achievement of the America First initiative,” Bessent wrote.

“Setting the course for Latin America, with a strong and stable Argentina that helps consolidate a prosperous Western Hemisphere, is clearly in our best interest.”

Bessent said the Treasury activated the Exchange Stabilization Fund under authority granted by Congress. He said the mechanism allowed the United States to assist Argentina at a critical moment marked by an acute liquidity shortage and immediate pressure on the exchange rate and financial stability.

“Only the United States could act with the speed we did in October to preserve market stability,” he said.

Argentina turned to the swap during a period of severe financial stress, when a shortage of hard currency threatened economic stability. The government needed foreign exchange to meet immediate payments, avoid a sharp devaluation of the peso and keep trade functioning. Without the support, officials warned of the risk of another crisis.

According to U.S. government documents, the funds helped contain currency volatility in the weeks leading up to Argentina’s Oct. 26 legislative elections.

Argentine officials described the agreement as temporary backing similar to an emergency credit line. It allowed the country to navigate weeks of uncertainty without resorting to harsher measures such as tighter controls or a sudden devaluation while it worked to regain access to private financing.

Bessent also responded to criticism from Democratic lawmakers, saying the fund “has never lost money” and that the full repayment generated “tens of millions” in gains for U.S. taxpayers.

He praised the direction of Argentina’s government, saying that once stability returned, private markets resumed covering the country’s financing needs. He credited President Javier Milei and Economy Minister Luis Caputo and said the United States expects to “continue supporting Argentina enthusiastically.”

Economist Salvador Di Stefano Haber told UPI the repayment is significant because “if you are not going to need it, there is no reason to use it.” He said Argentina has access to a $20 billion credit line in addition to about $44 billion in reserves.

“Overall, we are talking about $64 billion available,” he said. “They are not counted for technical reasons, but in practice they are there.”

He said the payment shows Argentina was able to withstand strong currency pressure ahead of the 2025 elections while also repaying the funds. He added that the government has met its sovereign debt obligations.

“Argentina is honoring its commitments as a matter of state policy,” he said. “It has a fiscal surplus, a capitalized central bank and it pays its debt.”

Economist and former lawmaker Martin Tetaz offered a similar view, telling UPI that reserve needs depend largely on access to external credit, especially lines provided by the U.S. government.

“That is why repaying the swap under the agreed terms was key,” he said. “It shows the financial relationship with the U.S. Treasury is sound.”

Tetaz said countries with full access to capital markets do not need to hold large reserves because they can obtain financing quickly. A close relationship with the U.S. Treasury further reduces that need, though markets still expect Argentina to build higher reserves to lessen reliance on bilateral support.

He pointed to recent central bank actions, including dollar purchases last week that lifted reserves to their highest level in three years. He said this helps organize foreign currency flows and ease short-term pressure.

“If the central bank can sustain the pace of purchases seen last week, that will rebuild reserves and restore confidence in the currency,” he said.

Not all economists share that optimism. Roberto Cachanosky told UPI that Argentina has effectively changed creditors.

“The debt to the U.S. Treasury is paid and a new one is assumed with international institutions,” he said. “We do not know the interest rate before or the rate now.”

Cachanosky also cited political resistance in the United States to President Donald Trump‘s support for Argentina, noting discontent among agricultural producers and criticism over a higher quota for Argentine beef imports. He questioned whether assistance would be available in a future currency crisis.

Looking ahead, Di Stefano said Argentina faces no major debt maturities in coming months. He estimated financing needs of about $10 billion through year’s end, which could come from the International Monetary Fund, other multilateral institutions and, if country risk falls, voluntary debt markets.

Even so, he expressed confidence, citing expectations of a record harvest and rising oil and energy exports. “That money likely will not be needed,” he said.

He added that reserves could grow through foreign direct investment in energy, mining, infrastructure and ports.