Read our Digital & Print Editions

And support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

Reports this week suggest that the EU is seeking a so-called ‘Farage Clause’ in its Brexit reset negotiations with the UK. Under the proposal, Britain would be forced to hand over compensation to the EU if a future UK Government reneges on any deal struck now by Keir Starmer.

The news comes some eight months since the last UK-EU summit which unveiled the first details of this ‘reset’ in relations promised by the then new Labour Government.

Despite the impression sometimes given by Government ministers, this was not, in itself, the reset agreement.

In fact, the only things nailed down were extensions to the existing provisions on fisheries and energy previously negotiated by Boris Johnson. There was also a political agreement outlining a new Security and Defence Partnership, although it fell short of the bespoke package which Labour’s 2024 election manifesto had envisaged, being similar to agreements the EU already has with other ‘third countries’.

Everything else announced at last May’s summit was aspirational, including statements made about the other three areas highlighted by Labour during the election.

Two of these, mutual recognition of professional qualifications and new provisions for touring artists, were not prioritized by the summit. Only the third UK priority was among those given more prominence, a ‘sanitary and phytosanitary’ (SPS) agreement on food and agricultural trade. A Youth Mobility Scheme, initially resisted by the UK but desired by the EU, was also among the prominent possibilities.

EXCLUSIVE

EXCLUSIVE: Nationalist vigilante groups, with links to Neo-Nazis, and the support of senior Reform figures, have been falsely claiming police backing while attempting to infiltrate local school networks

Nichola Lashmar

Since the summit, little progress has been made on realizing these aspirations. The only new agreement has been for the UK to join the Erasmus+ study exchange programme from 2027.

On the other hand, negotiations for the UK to participate in the EU’s SAFE defence procurement scheme have ended in failure. Now, although there are several other issues under negotiation, most attention focuses on an SPS agreement and an agreement to link UK and EU emissions trading schemes (ETS).

The potential deals on SPS and ETS share a particular feature, which is that both would require the UK to agree to ‘dynamic alignment’ with EU regulations and, with that, some role for the European Courts of Justice (ECJ). Politically, this makes them anathema to Brexiters, and they have come on to the agenda because an ECJ role was the only one of the previous Conservative Government’s Brexit ‘red lines’ which Labour have, very quietly, dropped.

Even so, for a long time Labour ministers tried to imply that these deals would be possible without dynamic alignment. But this was never realistic, and it has recently been reported that Starmer’s Government is preparing legislation to enable such regulatory alignment in these two areas, and perhaps others. This suggests, although there has been no announcement of it, that agreement on SPS and ETS is imminent.

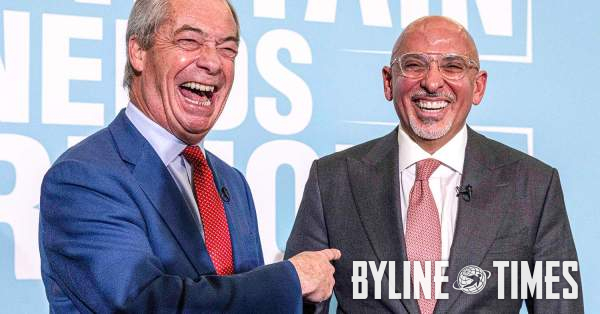

One issue which may still be under negotiation is what is being reported as the EU’s requirement for a ‘Farage clause’. This, it appears, would be a guarantee of compensation in the event of a future UK Government reneging on SPS, ETS, or other related agreements. It has a particular salience because both Nigel Farage and Kemi Badenoch have indicated that if they came to power then they would reverse agreements made with the EU by the Labour Government.

The ‘Farage clause’ reports are significant because this is perhaps the first time something widely discussed by commentators has been repeated by officials, albeit they are unnamed. It shows that domestic UK politics constitutes a real block on a substantive reset, something which applies even more strongly to more ambitious ideas about joining the EU, or the Single Market, or creating a UK-EU Customs Union. For, so long as there is no settled political consensus about closer post-Brexit relations with the EU, and every possibility that the next government will be ferociously opposed to closer relations, there are significant risks to the EU in reaching agreements with the present Government.

It often used to be remarked during the Brexit negotiations that British politicians seemed unaware that their EU counterparts could and did follow UK politics and media discussions. They still do, and anyone seeing how even the quite modest aspirations of Labour’s reset attract such ferocious hostility could hardly conclude, no matter what opinion polls show about declining support for Brexit, that the anti-EU fervour that led to it has now abated. Meanwhile, the unpopularity of Keir Starmer’s Government makes the possibility of Labour winning the next election doubtful at best. So, despite having no governmental responsibility, Farage and his allies are able to exert considerable power.

This does not mean that SPS, ETS and other agreements will not be reached, subject to the EU receiving sufficient guarantees, and it is highly likely that the Government will provide these. An SPS deal, in particular, seems to be baked into Labour’s plans and it is very hard to see it not going ahead given the news of the planned legislation to enable it. In these kinds of areas, it is relatively easy, through compensation agreements, for the EU to insure against the risk of Farage. They are, after all, economic deals within discrete policy areas and, as such, economic compensation mechanisms can be reasonably effective. In that sense, the Farage threat to Labour’s reset can be circumvented.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

However, what the Farage clause reports tell us is that he and other Brexiters hold something close to a veto on deeper forms of agreement than those envisaged by the limited scope of Labour’s reset. That is bad news in terms of addressing the multiple economic costs of Brexit, but it is not what makes Farage’s ‘power without responsibility’ so dangerous. Its real threat is to building substantive defence and security agreements with the EU, just when they are needed to face the urgent threats posed not just by Putin’s Russia but Trump’s America.

Those threats mandate immediate progress towards very close UK-EU cooperation on conventional defence, as well as cyber-defence and intelligence capacity. But creating such structural, institutionally-shared capacity goes way beyond the economic sphere and, were it to be agreed but then reneged on, economic compensation clauses would not provide an adequate safeguard.

If the EU is to reduce its enmeshment with US security because Trump has made Washington an unreliable partner, it is hardly likely at the same time to substantially deepen its reliance on an ally prone to similar unreliability. After Brexit, and with Farage in the offing, that is exactly what the UK is for the EU. And for the UK that means that, as well as being made poorer each year by Brexit, it is made more vulnerable to those who would do it harm.