A man whose gut brewed alcohol every time he ate carbs has finally found relief. Researchers traced the bizarre condition, auto-brewery syndrome (ABS), to alcohol-producing bacteria in his gut and successfully treated him using capsules derived from a healthy donor’s stool.

This unusual case, now detailed in a comprehensive study published in Nature Microbiology, opens new doors for understanding the link between gut microbes and systemic illness. Once dismissed as a fringe condition, ABS is gaining serious scientific attention, particularly as researchers confirm its biological roots and develop viable treatments.

Auto-brewery syndrome occurs when microorganisms in the gut convert carbohydrates into ethanol, leading to involuntary intoxication. The syndrome is extremely rare, fewer than 100 cases have been documented globally, but its consequences can be life-altering. Patients often face legal and social consequences before receiving a proper diagnosis. In this latest study, scientists from UC San Diego and Mass General Brigham identified specific bacterial strains and fermentation pathways responsible for ABS, paving the way for targeted treatments like fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

A Rare Condition Finally Understood

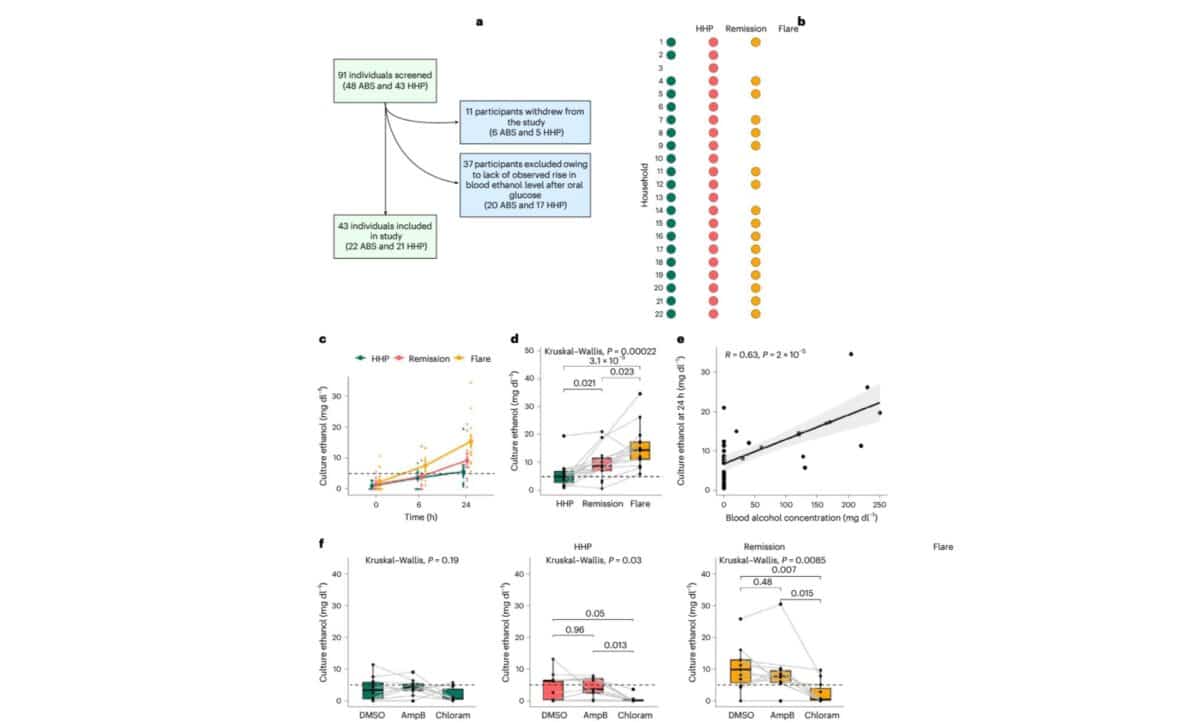

The breakthrough came from an observational study of 22 patients with ABS and 21 household partners, which offered a unique window into the disease. According to the study published in Nature Microbiology, stool samples collected during active ABS flares produced significantly higher levels of ethanol in lab cultures than those from healthy partners or from ABS patients in remission.

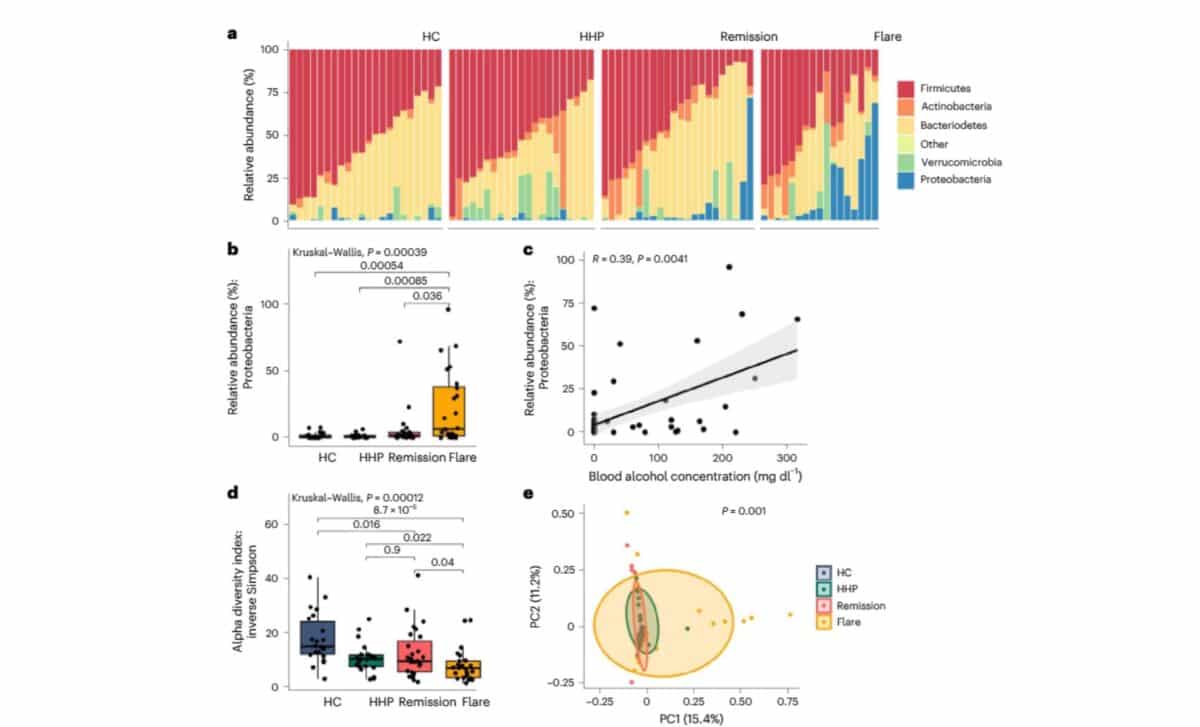

The samples showed a notable overabundance of Proteobacteria, particularly Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. These bacteria were shown to convert sugars into ethanol through various fermentation pathways. One of the study’s lead authors, Dr. Bernd Schnabl of UC San Diego, explained in a press statement that “these microbes use several ethanol-producing pathways and can drive blood-alcohol levels high enough to cause legal intoxication.”

The researchers also noted that fungal overgrowth, long suspected as the main cause of ABS, was not significant in the majority of the cases they studied. While earlier reports, including one from a US medical center in 2017, attributed ABS to brewer’s yeast like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, this new analysis emphasized the bacterial role instead.

How Gut Microbes Push Blood Alcohol beyond the Legal Limit

During a flare, some ABS patients reached blood alcohol concentrations as high as 136 mg/dL, well above the US legal driving limit of 80 mg/dL. Lab tests showed that stool cultures from these individuals could produce more than 14 mg/dL of ethanol within 24 hours, compared to just 5 mg/dL in samples from healthy controls.

Ethanol production was particularly linked to bacterial fermentation pathways, including the mixed-acid and heterolactic pathways. These routes allow microbes to process glucose into ethanol and other byproducts under anaerobic conditions. Enzymes like alcohol dehydrogenase, central to ethanol production, were also found in much higher quantities during ABS flares.

According to the study’s authors, remission samples displayed higher gene expression for the TCA cycle, a pathway linked to acetate production and ethanol breakdown. This suggests that a shift in microbial metabolism may help explain why some patients go into spontaneous remission, while others experience recurring episodes.

One Man’s Recovery through a Fecal Transplant

The study also tracked the dramatic recovery of one patient, a retired US Marine officer in his 60s, who developed ABS after receiving several rounds of antibiotics. His symptoms were severe and persistent. According to a New Scientist report, he was frequently intoxicated without drinking, eventually requiring a breathalyzer lock on his car.

After failed attempts with antifungal treatments and dietary changes, he reached out to Dr. Elizabeth Hohmann, an infectious disease specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. Initially skeptical, Hohmann reconsidered after speaking with the patient’s wife. In collaboration with Schnabl, she approved a fecal microbiota transplant using capsules made from the stool of a highly healthy donor.

The first transplant brought three months of remission, followed by a relapse. A second round, this time with broader antibiotic pretreatment and six months of monthly capsule dosing, resulted in over 16 months of symptom-free remission. Researchers observed that his gut microbiome had permanently shifted to resemble the donor’s, with a notable decrease in E. coli and fermentation pathway activity.

According to the Nature Microbiology study, this patient’s recovery correlated precisely with reduced ethanol production, normalized blood alcohol levels, and improved liver enzyme readings. His family reportedly told doctors that his “old self” had returned.

A Path Forward for Diagnosis and Treatment

The findings offer more than anecdotal hope, they suggest a framework for diagnosing and treating ABS. Rather than relying solely on supervised alcohol tests, future diagnostics could examine stool samples for specific microbes and metabolic activity. The research team also highlights the potential of targeting microbial fermentation enzymes instead of just focusing on bacterial species.

Dr. Hohmann said in a press release, “Auto-brewery syndrome is a misunderstood condition with few tests and treatments. Our study demonstrates the potential for fecal transplantation.” The study’s detailed microbial and metabolic profiling also hints at wider applications, possibly extending to conditions like liver disease driven by gut-derived alcohol.

While larger clinical trials are underway, this study marks a turning point in how ABS is understood and managed. For patients dismissed for years as secret drinkers, the evidence is finally catching up with their symptoms.