The Welsh Government’s 20% stake in Verona Pharma was sold before the firm hit the jackpot

Pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co bought out Verona Pharma for £10bn last year(Image: )

Verona Pharma is one of the success stories of UK science. The firm develops treatments for patients with chronic lung and respiratory issues. It hit the jackpot in 2024 when its inhaled treatment for COPD, Ohtuvayre, was approved for use in the USA.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a huge market in the States with an estimated 16 million patients affected. Pharmaceutical giant Merck swooped in and bought the one-time minnow Verona Pharma for $10bn (around £7.5bn).

It was a huge payday for the shareholders who had stuck with the company since its early days on the Alternative Investment Market when it had a valuation of just £20m.

The Welsh Government had been one of those early shareholders, buying a 20% equity stake in exchange for giving the company £4.6m to invest. Yet by the time Verona Pharma hit the big time, Wales had sold its entire stake.

The Welsh Government’s foray into life sciences investment had begun back in 2012 when then First Minister Carwyn Jones announced plans to launch its own equity investment fund to back the life sciences sector in Wales.

It was a strategy driven by its plain-speaking then Economy Minister, Edwina Hart.

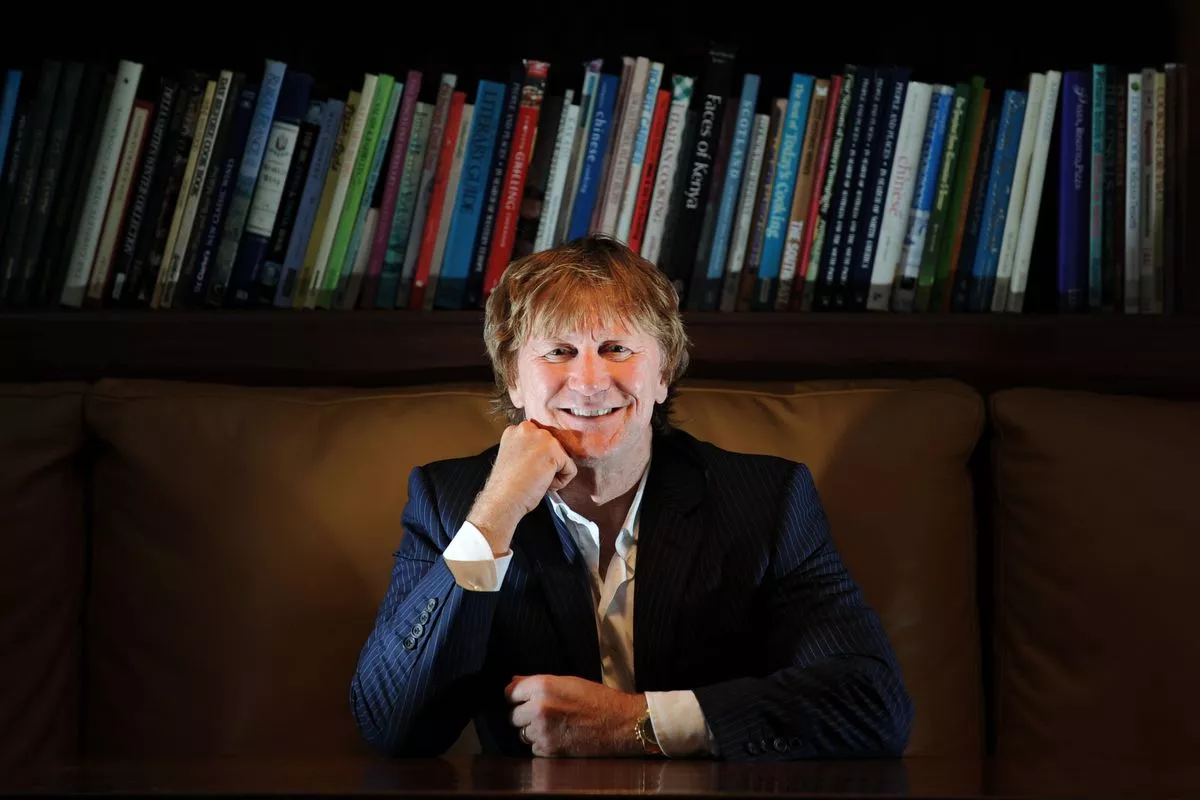

Biotechnology entrepreneur Professor Sir Chris Evans(Image: )

She brought in the ebullient Port Talbot-born life sciences serial entrepreneur and investor Sir Chris Evans and the pair painted a vision of a fund designed to put Wales on the global life sciences map.

The £50m Wales Life Sciences Investment Fund (WLSIF) promised to bring life sciences firms into Wales, allow them to grow here and dangled the hope of a return for the taxpayer.

Some civil servants had reservations about the Welsh Government committing taxpayers’ money to a sector where there is no guarantee of success. Huge capital demands, the difficulty of clinical trials and regulatory approval all make life sciences a difficult sector.

With high cash burn rates, there are also plenty of examples of founders of pre-revenue life sciences firms in the UK who, no sooner having raised several million pounds, are back in the marketplace seeking another round just to stay afloat. Even if they survive through numerous funding rounds some become so disillusioned and diluted (on ownership) that they resemble a proverbial bottle of Robinsons Barley Water on the last day of Wimbledon.

Former Welsh Government minister Edwina Hart set up the £50m Wales Life Sciences Investment Fund.(Image: HUW JOHN)

The Welsh Government’s £50m WLSIF was launched in 2013 to a fanfare of PR and upbeat projected promises on return.

As the Welsh Government was not a fund manager, it needed to find someone to run the fund on its behalf. The WLSIF was to be run on a discretionary basis; in other words, it was left to the fund manager to decide which companies to invest in on behalf of the Welsh Government.

The Welsh Government’s wholly owned investment bank entity, Finance Wales, held a search for a fund manager and there was one bidder: Arthurian Life Sciences, which was chaired and majority-owned by Edwina Hart’s ally Sir Chris.

The fund’s first investment was in Merthyr-based clinical research business Simbec Research. This later proved one of the few success stories for the Welsh fund.

Some six years later, what had become the Simbec-Orion Group was bought out by its management and generated a £20m capital return for the fund, which was passed back to the Welsh Government.

That maiden investment into Simbec, which overall received £8m from the fund, was quickly followed by £5m into AIM-listed, Guildford-based ReNeuron. The stem cell regenerative company was also backed by a number of institutional investors in a total equity round of £25.5m.

Backers included Invesco, headed by the now disgraced financier Neil Woodford. As a condition of the £5m investment, ReNeuron agreed to relocate from Surrey to Bridgend in south Wales. The Welsh Government also provided grant funding of £7.8m.

ReNeuron, which received a follow-on investment of £5m in August 2015 from the WLSIF, later collapsed into administration. It still trades today from Bridgend, having been acquired out of an insolvency process.

Verona was another investment. The then Alternative Investment Market (AIM) listed firm secured a £4.6m investment from the fund in 2014.

As with ReNeuron, a condition of the funding was that it relocated to Wales – although this never quite happened. It had a presence in Cardiff but a later review found that the fund manager had tried to make this happen but that despite efforts “to trigger delivery of the full relocation obligations… there was a lack of enforcement mechanisms to move it beyond partial compliance”. Verona’s head office stayed in London.

With ReNeuron looking likely to require additional equity, and Arthurian at an advanced stage in seeking to invest in two other life sciences firms, CeQur and Apitope (£3.36m and £3.9m respectively which was matched by Welsh Government separate backing), it didn’t have sufficient headroom within the fund to close the deals.

To get around this, Arthurian secured a £3m loan from Finance Wales. And to repay the loan Arthurian sold half of the fund’s stake (to the value of £3m) in Verona between 2015 and 2016. It was a decision that flew in the face of taking a patient capital approach to investment and particularly as this was a government backed fund with no external fund shareholders to exert pressure.

While Arthurian was a discretionary fund I cannot imagine they didn’t sound out Finance Wales and Welsh Government officials in advance before disposing of the shares.

By the end of its financial year to the end of December, 2016, the fund’s equity stake in Verona, after the selling of shares, had been whittled down from 20.5% to only 4.1%. As well as the disposing of half the fund’s shares, the fall was also due to the dilutive impact of not participating in a £45m fundraising for Verona with existing and new institutional investors in the summer of 2016.

The following year, management of the by-then fully-invested Welsh fund passed to Arix Capital Management following the acquisition of Arthurian by its parent company Arix Bioscience.

With pressure mounting due to the difficulties of many of the fund’s investments and growing political criticism, as well as concerns raised in an Auditor General report, the Welsh Government – with Edwina Hart and Sir Chris long gone – closed the fund. Its wind-down was overseen by the Development Bank of Wales.

Prior to the winding up of the fund, Verona delisted from AIM to focus solely on New York’s Nasdaq exchange.

With Verona effectively exiting Wales, the Development Bank of Wales instructed Arix to sell the remaining 263,750 Verona Nasdaq shares. This was executed in 2022.

The shares were sold at a time when the share price was just over $10. Fast forward to last year, and Verona’s $10bn acquisition by Merck equated to $107 per share.

The sale of all Verona shares (including those originally sold while it was listed on AIM) generated £5.77m. So, there was a final profitable margin of just over £1m on the original investment of £4.6m.

If the Welsh Life Sciences Investment Fund had not sold its shares, it would not have had a 20% stake in Verona just prior to the Merck takeover, which would have been worth £2bn. The Welsh stake would have been diluted in some of Verona’s later fundraisings.

However, even taking that into account, the Welsh investment in Verona would still have been a goldmine. It would have propelled the fund’s performance into best of class for investment in life sciences, especially for a relatively small fund limited to a distinct geographic area (Wales).

What a return could have been is difficult to estimate, as it would have been further eroded by the subsequent fundraising rounds into Verona post 2016, including £150m secured in 2020 when it was both listed on AIM and Nasdaq. However it could well have exceeded or at least matched the entire value of the fund.

As it is, the Welsh Life Sciences Investment Fund made 11 investments – of which two were follow-on deals – and closed in 2023 with around £27m having been written off.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but perhaps the share certificate for the remaining shares in Verona after the first sale in 2015/16 should have quietly been put away in a top draw with the hope of better returns at some future point.

On the overall performance of the WLSIF fund, the Welsh Government could point to hundreds of new jobs created and safeguarded by the fund’s investments, the leverage from co-investment, and the positivity generated by a government seeking to back a sector with huge, but not yet fully realised, potential in the UK. But it cannot escape the fact that the fund failed to deliver an evergreen model where profitable exits were reinvested over the long term.

Investment in life sciences really is a big numbers game . The Welsh Government probably needed a £200m fund, even if invested over a 10-year period to ease demands on its annual budget, and one that made around 50 investments. Such a fund would also need potential new capital for follow investments.

That would have provided a greater chance for a few star performers being sold or floated to more than offset losses elsewhere. Governments are often accused of being risk-averse. However, for the Welsh Government and the WLSIF this was anything but.

However, with the WLSIF only executing 11 deals, the odds were stacked against it. In total just over £48m was invested in companies.

The total cost of the fund, including management fees, set-up costs and fees to professional advisers, was £52.5m. The fund’s biggest hit came with the collapse in 2022 of proton beam cancer treatment centre business Rutherford Health, in which it had invested £10m in equity as part of a £100m investment round in 2015.

With a network of clinics, it was, on the surface at least, at the lower-risk end of the fund’s portfolio. However its failure to secure NHS referrals – driven largely by reluctance from health boards – proved to be its undoing.

A spokesperson for the Development Bank of Wales said; “The Wales Life Sciences Investment Fund had a goal of economic development. It was designed as a financial instrument to attract life sciences businesses to Wales.

“The original investment in Verona Pharma in 2014 was £4.62m, but the fund manager chose to sell a significant proportion of these shares over 2015 and 2016. The remaining 263,750 Nasdaq-listed shares were sold in 2022, representing a full exit from the investment.

“Set up in February 2013, the fund launched with a five-year investment phase and a five-year realisation phase. Under this standard fund management contract, the fund manager endeavoured to exit all investments before the fund closure date of February 2023.

“In early 2018, the fund manager notified the Development Bank of Wales that Verona Pharma had started shifting its focus away from Wales. As it no longer planned to have a presence in Wales, it no longer fitted within the operating guidelines for the fund and therefore the Development Bank of Wales asked the fund manager to exit at the earliest commercial opportunity.

“In August 2022, the fund manager completed the sale of its remaining holding in Verona Pharma following positive trial results. The fund manager was responsible for the decision on the timing of the exit. The total receipts from the Verona exits were £5.77m.”