Eighty years after Liverpool’s Chinese seamen were rounded up and forcibly deported, their families are still searching for answers

Kellie-Ann Flower lays a bouquet in memory of her grandad at the memorial for the deported seamen at the Pier Head(Image: Moira Kenny)

It has been 80 years since Merseyside became the central focus of a national disgrace that saw families torn apart overnight. The forced deportation of thousands of Chinese seamen who had settled in Britain after supporting the country’s efforts during The Second World War was a scandal that was kept secret for decades – only coming to light thanks to the determined efforts of the children and grandchildren left behind.

Kellie-Ann Flower, 54, never got the chance to meet her grandad Chao Zay Foo, as he was deported long before she was born. Escaping the fall of Shanghai and subsequent Japanese invasion of China in WWII, Chao Zay Foo fled to sea and began working on the Blue Funnel line, the leading British shipping company trading to China at the time.

Like many Chinese seaman on the Blue Funnel line (owned by Liverpool shipping magnate Alfred Holt), he arrived in Liverpool to support the Allied war effort. Here he met Avril, and the couple married, had children and settled down.

But their humble life was brutally torn apart in July 1946, when thousands of Chinese sailors – including Chao Zay Foo – were forcibly deported by the British government.

Acting on government orders, Liverpool police rounded up thousands of Chinese men in Merseyside. Some were snatched off the streets, often in the dead of night, while others already onboard ships were forbidden from returning to the UK.

Adding to the tragedy, their families were not informed of the secret mass deportations.

Some wives went their whole lives believing they had been abandoned, while others feared their husbands had drowned at sea.

Children were robbed of their dads overnight, and often had to be looked after by grandparents or social services as their mums were left destitute, derided by society as “no more than prostitutes”.

Kellie-Ann said: “We believe my nan and grandad married in 1946 at the Chinese embassy, because she was listed as a wife and receiving a half wage – when the men were at sea, the wives could collect a half wage.

“Government records said all marriages that took place at the Chinese Embassy had been destroyed. But we know from the fact that she collected the wage she must have been registered as his wife.

“After the deportation my nan was destitute. She went to London; she didn’t actually know what was happening at the time; she thought he’d been posted to another ship. She fell on hard times and my dad went into an orphanage.”

Descendants of Merseyside’s lost Chinese seamen lay flowers at the memorial for the deported seamen at the Pier Head(Image: Moira Kenny)

This might have been the end of the story, were it not for Chao Zay Foo, who beat all odds to return to the UK in 1953 – eight years after he was deported.

He reunited with Avril and his son, and the family moved into a multi-family house on Upper Huskisson Street in the Georgian Quarter, where whole families were crammed into single rooms.

Kellie-Ann said: “In 1953 my grandad sneaked back to the UK, remarried my nan in a registry office, got my dad out of the orphanage, only to be caught and deported again.

“So my family was aware that he had been caught and deported the first time. But we didn’t know that all those other men had been deported too.

“My nan said ‘how could he? How could he break the law and get himself deported at a time like this?’. She was so angry with him. She held him personally responsible. She spent her whole life thinking he must have been a criminal for that to have happened to him.”

That all changed in 1998, when Kellie-Ann saw a Granada documentary about the plight of the Chinese seamen.

She said: “When the documentary came out we thought wow, this is not the story we had been told. Our family’s investigation started then. It’s been a real journey.”

Kellie-Ann started the Descendants of Liverpool Chinese Seaman group for surviving family members after the government finally acknowledged its “racist and coercive” deportations in a 2022 report. The group aims to find out all they can about their deported relatives through documents and DNA.

Kellie-Ann said: “The first deportations were a couple of weeks before Christmas. It was an horrendous winter and then men just didn’t come home.

“A lot of the mums didn’t want to speak about it because they were so angry and betrayed by what they thought their husbands must have done – that they jeopardised the family by breaking the law. That was what they were led to believe.

“Some families were lucky and they had grandparents who could look after children. But nearly all of them had to go and live somewhere while their mums got back on their feet. A lot of them couldn’t afford rent because they didn’t have a wage coming in, and its not like today where you’re a protected tenant. If you couldn’t pay on Friday, you were out on Friday.

“It cause real hardships, and not just that but the years of gaslighting and being told ‘it never happened’. Now the government has finally admitted it happened, but added in their report ‘but some of them chose to leave’, which I thought was the cruellest line. It has still left the families feeling unsure and abandoned.”

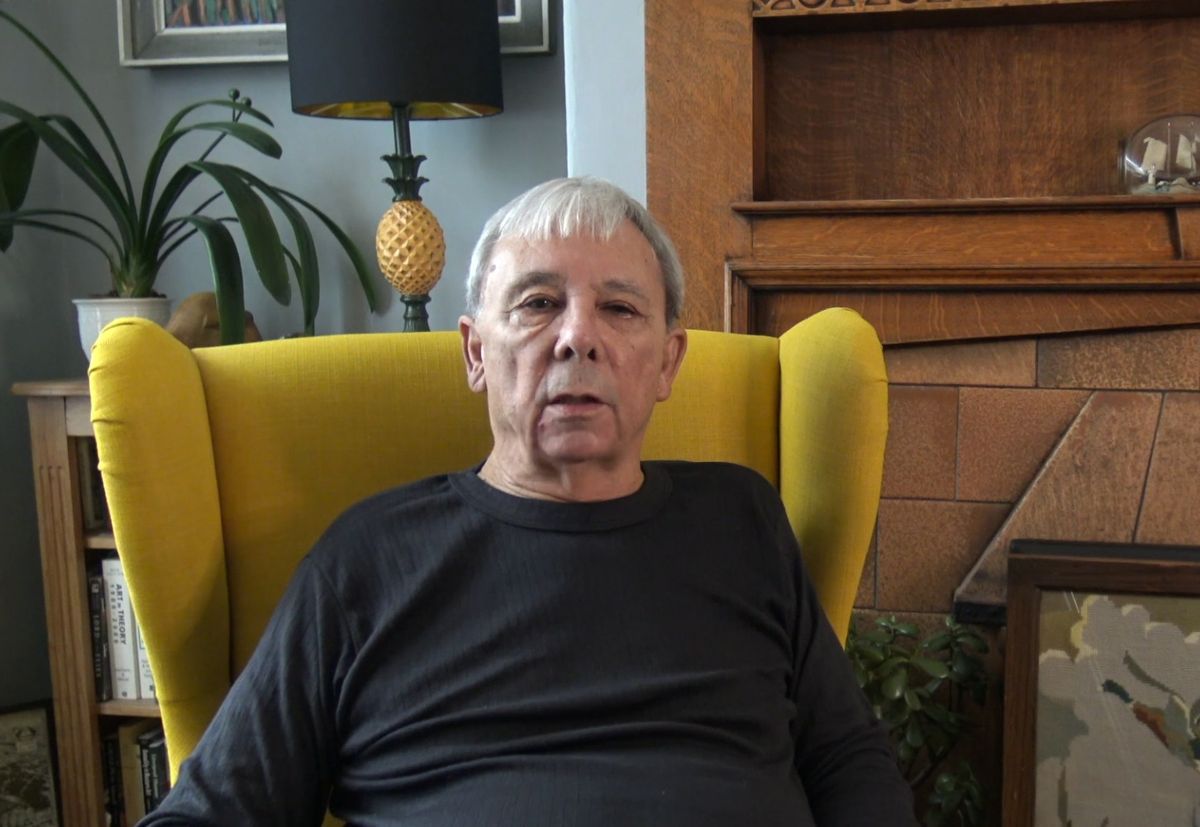

Peter Foo outside the famous arches at Liverpool Chinatown(Image: Moira Kenny)

Among those left behind was Peter Foo, whose father was deported when he was two. In a 2023 interview prepared for the Chinese and British Exhibition, he said: “We never spoke about it. My mother never spoke about it because we never discussed anything. I’ve got a funny feeling she never discussed my father purely because she thought he had just left us and that was it.”

Keith Cocklin, who was adopted by his mum’s second husband years after his dad was forcibly deported, said: “I often wondered what happened to my real father and they told me that he had been taken away. I didn’t ask any questions. It was only when I was 16 that I asked the question what happened to him, and that’s when I found out.”

Keith Cocklin in his interview as part of the Chinese and British Exhibition held in Central Library, Liverpool. Curated by The Sound Agents in partnership with Liverpool Chinese families, The British Library and the Living Knowledge Network(Image: The Sound Agents 2023)

Brothers John Sze and Joseph Phillips Sze also lost their dad in the 1940s. Joseph said: “My grandmother, she gave a lot of help to my mother. She was always supportive of her, as was uncle Joey. They were supporting everything she did. She was working seven days a week just to put a crust on the table.

“We didn’t actually miss our father because we didn’t have one. We didn’t know who he was. All we knew was Uncle Joey as our father, and our mother bringing in the bacon, and our grandmother supporting her. There was no sense of a father at all.”

His older brother John said: “He [Joseph] was only a baby, but I remember being a bit lonely. When you go to school and you see the other children have got a dad. It was very lonely.”

John Sze and Joseph Phillips Sze in their interview as part of the Chinese and British Exhibition held in Central Library, Liverpool. Curated by The Sound Agents in partnership with Liverpool Chinese families, The British Library and the Living Knowledge Network(Image: The Sound Agents 2023)

Kellie-Ann has spent years trying to trace lost family members – but the endeavour has proved a difficult one, as undercover officers would reportedly carry out home visits to seize documents and erase any record of the deported seamen.

Despite claims of “repatriation”, many Chinese men were not returned to China, but were simply dropped off at various Asian ports in Singapore, Vietnam, and India.

She said: “England destroyed most of their records. But if you’ve got international reports you can see the ships docking in other countries, so we’ve managed to confirm if their dads worked for Blue Funnel, which increases the likelihood that they were deported.

“But we cant find a physical trace of any deported men. Only one managed to write home from Singapore. All he wrote was ‘I’m starving to death, can you send me £10?’. Only after the deportations, his wife was destitute on £1 a week with children to care for.”

Peter Foo’s parents, before his father was forcibly deported by the British government(Image: Moira Kenny)

She added: “It can’t be swept under the rug. It’s burning out of us. There’s nothing we can do to control the need to know. That the children who were left behind, a lot of them had some hesitation, wondering ‘did my dad abandon me? Am I looking for someone who didn’t want me?’ because that was the attitude they grew up with.

“But my generation don’t care. The government deported my grandad and I have a right to know what happened to him.

“To think he survived the fall of Shanghai, he survived the invasion, he worked in a foreign country all the way from home, he finally found a little island and a family to call his own, and all that was taken away from him as well. I need to know that he had a life.

“The truth is important. It’s all well and good laying flowers at the Pier Head in their memory. But we need to lay flowers on their graves. It’s so important in Chinese culture to honour your ancestors and we don’t even know where they are. They were heroes, and they were thrown away like dirt.”