President Donald Trump announced, on the sideline of the World Economic Forum in Davos, that he and NATO secretary general Mark Rutte had “formed the framework of a future deal” on Greenland. This seeming deescalation of the US-European standoff over the island avoids further American tariffs and resultant EU countermeasures—and the slippery slope toward a militarised crisis between NATO allies.

Alliance relations might be strained: but using NATO to improve US-European cooperation and counter Russian nuclear coercion could be a silver lining to this episode

The deal will also likely result in a larger American military footprint in Greenland to fend off apparent Chinese and Russian ambitions in the Arctic, and to protect the continental United States from complex and evolving nuclear missile threats. Greenland’s geography makes it a critical piece of Trump’s “Golden Dome for America” missile-defence architecture.

Alliance relations might be strained: but using NATO to improve US-European cooperation and counter Russian nuclear coercion could be a silver lining to this episode.

Greenland: From the cold war to now

With the first Soviet nuclear test in 1949 and intensifying cold war tensions, US concerns grew about its vulnerability to Soviet strategic bomber attacks from across the Arctic. To detect such attacks early in their approach, US defence planners envisioned three lines of early-warning radars stretching across North America, with additional stations in Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

Work on the Greenland sites and bases was facilitated by a US-Danish agreement, signed in 1951. This allowed the parties to “take such measures as are necessary or appropriate to carry out expeditiously their respective and joint responsibilities in Greenland, in accordance with NATO plans”.

The northernmost Distant Early Warning line of radars became operational in 1957 but quickly turned obsolete with the advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM). Where Soviet bombers took hours to reach the continental US, its missiles would now only take 20-30 minutes to deliver their nuclear payloads. This required a new set of radars; Greenland’s geography meant the island continued to be critical in detecting incoming threats.

Though early warning would not allow US defences to intercept all—or perhaps any—Soviet nuclear missiles, it would increase the survivability of the national command authority and of US nuclear forces to launch strikes in response to an attack. They could achieve deterrence by assuring retaliation.

After the cold war, the US withdrew most of its troops in Greenland and vacated many military installations. Today, the US only maintains Pituffik Space Base, where just under 200 US Space Force personnel support missile warning and space surveillance missions. Trump’s Golden Dome plan now calls for an expansion of the US missile-defence posture in North America—and Greenland.

Anything, anywhere, all at once

Trump’s desire for comprehensive missile defence goes way back. At the release of his first administration’s Missile Defense Review in 2019, he announced: “Our goal is simple: to ensure that we can detect and destroy any missile launched against the United States—anywhere, anytime, anyplace”. The document itself was more modest, gearing up to defend against “rogue state and regional missile threats” only, while relying on nuclear deterrence for the “large and technically sophisticated” arsenals of Russia and China.

Six years after the review, the Golden Dome announcement moved the administration’s level of ambition to match the president’s own: to defend against conventional and nuclear-armed “ballistic, hypersonic, advanced cruise missiles, and other next-generation aerial attacks from peer, near-peer, and rogue adversaries”.

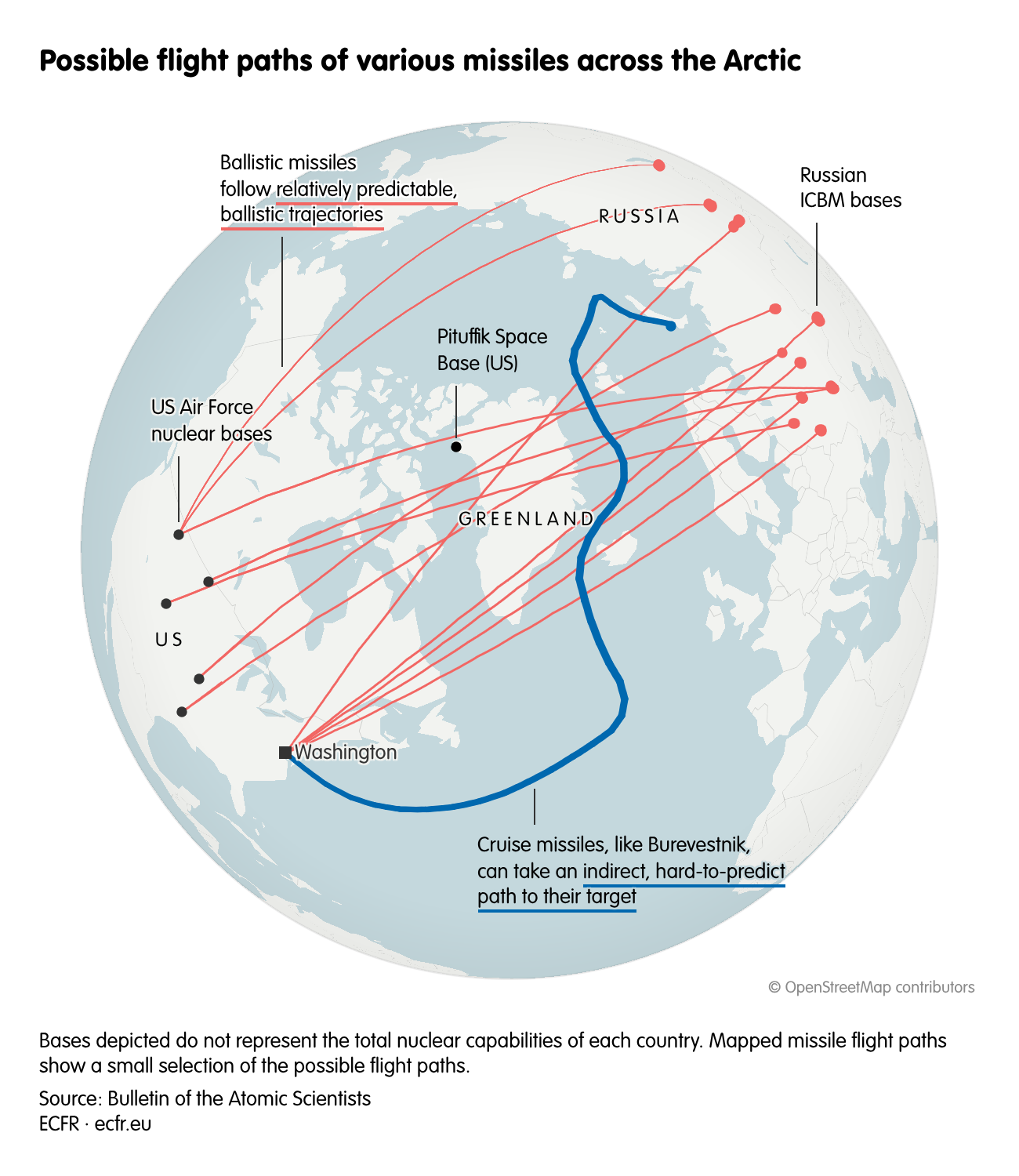

Hypersonic and cruise missile threats present a particular problem for the legacy missile-defence architecture designed to defend against traditional ballistic missiles. Whereas the latter follow relatively predictable ballistic trajectories into outer space and down again, the former take indirect and relatively low approaches to their targets. Russia has been developing its Burevestnik, a nuclear-armed, nuclear-powered cruise missile with virtually unlimited range, specifically to evade US missile defences.

To execute the Golden Dome ambition, the Pentagon seeks to create terrestrial and space-based systems, inside the continental US and beyond, to identify, track, target, cue and intercept missile threats to the US homeland.

As during the cold war, Greenland is prime real estate to host new sensors to detect ballistic missiles—and cruise and hypersonic missiles—additional space surveillance and satellite ground stations, potentially alongside missile interceptors to launch at incoming threats. The president wants Golden Dome to be “fully operational” by January 2029 at a price tag of $175bn.

The tortured defence-analysts department

This level of ambition—to achieve comprehensive air and missile defence, in less than four years, at such a cost—is dubious to say the least. So is Trump’s claim that the US needs to own Greenland to implement his plans.

When US military leaders explored acquiring Greenland in the 1950s, the state department concluded that such a course “could be extremely dangerous for the retention of our activities there, and could hardly improve our status, since we are permitted to do almost anything, literally, that we want to”. The same is true today. Then, as now, its alliances are a key enabler of persistent US advantage in space, and Danish governments have repeatedly engaged the US on security cooperation in the Arctic without much of a response from Washington.

Similarly, warnings that “Russia or China will take Greenland” if the US does not move first ring hollow when the nefarious presence of rogue actors at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago retreat might well be larger than on the island.

Europeans on ice

Nevertheless, Europeans should offer to cooperate on Arctic security and missile defence. This would allow them to gauge whether Trump is interested in attaining mutual benefits, to advance core European security interests in that region and to counter Russian nuclear coercion. Their cooperation should include European investments in space and maritime situational awareness around and above Greenland, just as those being undertaken in Europe, and a larger European military presence on the island.

The US and Denmark already updated their 1951 agreement once, in 2004, and Denmark has recently offered to amend it again to account for changing geopolitical circumstances.

If Trump bites, the US and NATO win; if he doesn’t, a larger European stake in Greenland would raise the political costs of US action to take the island. Trump backing down in Davos shows that he is not insensitive to dire political costs—at least for now.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.