In the days after Christmas last year, there were murmurs on the Russian social media claiming that Denis Kapustin, a far-right Russian opposition leader fighting alongside Ukraine, had been killed.

A Moscow-born Russian nationalist, Kapustin painted a complicated history of espousing his political agenda while remaining steadfast in his support against Russian imperialism and the invasion of Ukraine.

He moved to Kyiv in 2017, and founded the Russian Volunteer Corps (RDK) and fought against Moscow’s full-scale invasion in 2022, earning him a place on Russia’s federal registry of “terrorists and extremists” in March 2023.

On the morning of 27 December, confirmation arrived from the RDK. “Last night, our commander, Denis ‘White Rex’ Kapustin, died heroically while carrying out a combat mission in the Zaporizhzhia sector of the front. According to preliminary reports, it was an FPV drone [that killed him],” they posted on their official Telegram channel.

Russian war bloggers did the rest. Within hours, the news spread like wildfire, with pro-Russia accounts cheering the fall of one of the fiercest opponents of Vladimir Putin.

But their celebration was short-lived. On New Year’s Day, Kyrylo Budanov, then chief of the Ukrainian intelligence services (GUR), released a video statement, alongside a very much alive Kapustin.

Russian Volunteer Corps commander, Moscow-born Denis Kapustin, in Ukraine in 2023 (Photo: Viacheslav Ratynskyi/Reuters)

Russian Volunteer Corps commander, Moscow-born Denis Kapustin, in Ukraine in 2023 (Photo: Viacheslav Ratynskyi/Reuters)

“Welcome back to life, Denis Kapustin,” Budanov quipped in the video shared with The i Paper.

The plot unfolded in the quiet corridors of the Ukrainian intelligence services. “Russia had ordered the murder of Denis Kapustin by the special services of their state, and allocated half a million dollars for it,” a GUR official shared.

With the knowledge of an impending attack on Kapustin at hand, the Ukrainian services got to work to not only foil the assassination attempt but also use the opportunity to hoodwink the Russians.

“As a result of the complex special operation which lasted more than a month, [Kapustin’s life] was saved, and a circle of people – the ones who ordered the crime in the Russian special services and the executors, were also identified,” they said.

A video showing a fake assassination operation in which two drones appear to hit a minibus carrying Kapustin (Photo: Defence Intelligence of Ukraine)

A video showing a fake assassination operation in which two drones appear to hit a minibus carrying Kapustin (Photo: Defence Intelligence of Ukraine)

A believable story had to be created, then evidence was built to support the “legend” that Kapustin had indeed perished. This was created in the form of a series of videos. “The first, from the perspective of the attack drones, showed the drone flying into the minibus carrying Kapustin, and a second clip showed the aftermath of the strike — a burning car. That was all that was needed,” the official said.

Ukrainian operatives, posing as executioners, presented the footage to Russian special services, who believed the evidence and paid them the bounty. Although the officials did not share how the payment was received, Russians are known to recruit and pay saboteurs online using cryptocurrency.

“This will be used to significantly strengthen the combat capabilities of the GUR special forces,” said a proud Budanov in the video.

How Ukraine is using deception and decoys

This isn’t the first time that Ukraine has used deception and sabotage to fight back against Russia.

Outnumbered on the battlefield and with far fewer resources at their disposal, especially as the US wavers in its support, the Ukrainian defence forces are facing a significant increase in attacks, in volume and intensity.

However, they have held fast in part due to unconventional and sophisticated operations involving masterful use of deception.

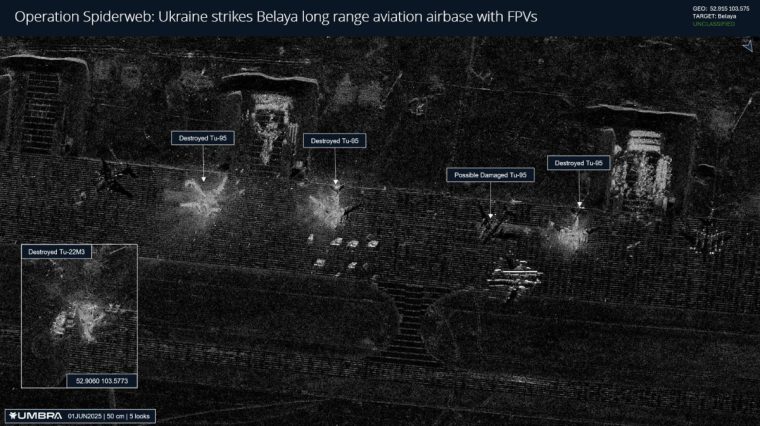

Most prominent was last June’s Operation Spiderweb, a covert attack during which more than 100 Ukrainian drones were simultaneously released to attack airbases deep inside Russia, some as far as 4,000km into its territory. Nearly 40 military aircraft were damaged, according to Ukraine.

A satellite image shows the aftermath of a Ukrainian drone strike on Russia’s Belaya air base last summer, with significant damage to Moscow’s fleet of strategic bombers (Photo: @CSBiggers/@UmbraSpace)

A satellite image shows the aftermath of a Ukrainian drone strike on Russia’s Belaya air base last summer, with significant damage to Moscow’s fleet of strategic bombers (Photo: @CSBiggers/@UmbraSpace)

“There’s been a technological leap [in wars]… the use of drones, electronic warfare, space-based technology has made the battlefield a lot more visible, and surveillance and reconnaissance is much easier,” said Nick Reynolds, research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute think-tank in London.

Increased battlefield transparency, along with the use of machines to process large volumes of data, had marked a shift in the use of C2D2 – camouflage and concealment to deception and decoys – in conflicts, Reynolds said,

“We’re seeing a shift from the former two aspects (camouflage and concealment) to the latter (deception and decoys), because it’s harder to conceal or hide things, so what you do is create false positives and uncertainty, make the targets more difficult for the enemy,” he said.

Ukraine understood this from the early days of the invasion, and often leaned into the use of makeshift decoys to distract Russian forces and protect high-value infrastructure, sometimes using store-bought mannequins, for example.

A mannequin dressed as a soldier near a road in Kharkiv in 2022 (Photo: Bernat Armangue/AP)

A mannequin dressed as a soldier near a road in Kharkiv in 2022 (Photo: Bernat Armangue/AP)

Additionally, economic and supply chain issues had boxed them into using alternative means of warfare. “And they’re getting very good at it, at understanding how to utilise deception, how to protect against it,” Reynolds said.

In the early days of the war, Ukrainian forces posed mannequins with toy guns in Kharkiv, in the north-east of the country, and were notably successful in slowing down the advancing Russian forces.

Since then, the Ukrainian use of decoys has not only grown more sophisticated but also fostered an industry, with private companies like Metinvest and Inflatech, producing them to manipulate Russian forces and foil attacks.

“In the early days of the war, we were seeing a very high proportion of Russian forces striking decoys, dummy positions, and a relatively low proportion of effective, precise targeting of high-value assets on the battlefield,” Reynolds said. “The Ukrainian military was able to operate at the scale that left the Russians struggling to keep pace in their ability to discriminate, identify and hit targets.”

The long history of military decoys

There is historical precedent in the use of decoys in warfare, Reynolds explained. “The Second World War is a good example of extensive use of deception, such as Operation Bodyguard, which was the overarching deception strategy.” This was planned by Allied powers in the 1940s, involving the use of inflatable tanks, fake radio traffic and false intelligence to mislead the Germans during the build-up to the Normandy Landings.

Before that, in the First World War, France built an entire replica of Paris 15 miles outside of the city, complete with Arc de Triomphe, Opera house, Gare Du Nord and Champs-Elysées, to fool German bombers.

The aftermath of a car explosion in southern Moscow last month that killed a senior Russian officer, Lieutenant General Fanil Sarvarov (Photo: Sefa Karacan/Anadolu)

The aftermath of a car explosion in southern Moscow last month that killed a senior Russian officer, Lieutenant General Fanil Sarvarov (Photo: Sefa Karacan/Anadolu)

However, Reynolds added, unlike the former Soviet military, where deception was an integral part of war, Western militaries focused more on economy of force: “The structure of Soviet armies, its doctrine, its military culture, like maskirovka [literally “something masked”] placed an importance on deception, dictating that conventional forces would put about 30 per cent of their effort into their deception plan.”

The Ukrainians know this and have used it to their advantage. “Ukrainian forces, I would say, have adopted their own doctrine culture in some areas…and now they’re really evolving along their own path. The Ukrainian military is quite unique at the moment, in many ways,” Reynolds said.

How Ukraine is outgunning Russia

While Russia and Ukraine both employ similar techniques of deception and sabotage, Kyiv has outgunned Moscow when it comes to domestic sabotage campaigns, said Nichita Gurcov, a senior analyst at monitoring group Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (Acled).

“Ukraine has expanded its sabotage footprint from occupied territories to Russia itself and is mounting increasingly sophisticated acts of sabotage by combining local recruits and resistance groups with professional military and intelligence,” Gurcov said.

Your next read

While deception, decoys and sabotage do not necessarily hinder either side’s ability to continue the conventional war, they do have a psychological effect of inflicting symbolic damage, he added.

The optics of a successful sabotage operation and an active shadow war helps Ukraine to build morale. That may have been one of the intentions of the operation involving Kapustin.

“That kind of activity shapes people’s perceptions of what is possible and impacts morale, not just within Ukraine but also among international audiences,” Reynolds said.