Buy a copy of the TIME100 Health issue here

Health officials and the public argued that the WHO was too slow in responding after the first COVID-19 cases emerged from China (a WHO member), and that it did not take a stronger stand against China when the country failed to follow through on agreements to allow WHO scientists in to learn about the new virus. Public-health experts say the two years it took for the WHO to admit the SARS-CoV-2 virus could be transmitted through the air—long after ample evidence was available—hampered attempts to control spread, as the organization focused mostly on advising people to wash their hands.

“No question in my mind that WHO was far too slow on the initial response,” says Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University School of Public Health who served as President Biden’s chief COVID-19 advisor and interacted regularly with Ghebreyesus during the pandemic. “Even after China informed WHO formally, for a while WHO took China at its word on almost all issues. My view is that WHO should be an independent organ that assesses its own data.”

Ghrebeysus says he, and the WHO, did what was in its power to do to persuade Chinese president Xi Jinping to share data and allow WHO teams to visit the hardest hit areas. “We went there and convinced him to allow us to send a team; he said OK,” he says of his visit to Beijing to speak to Xi. But the WHO has no authority to force China to make good on that promise, he says. “We couldn’t do more than we did, because it’s up to governments to cooperate. All the allegations, especially that we were not doing what we were mandated to do with China, is based on lies. We have done what we were expected to do and even beyond.”

In response to criticisms of the WHO’s response to COVID-19, Ghebreyesus spearheaded the Pandemic Accord. For the past three years, all of the WHO’s 194 member states have planned and negotiated the accord, laying out how the world would respond to any future pandemics. A final version was reached in April—with everyone on board but the U.S.

To Ghebreyesus, this serves as evidence of WHO’s willingness to acknowledge its mistakes and fix any problems. During the vaccine rollout, for example, manufacturing countries—primarily the U.S.—reserved doses for its populations while people in lower resource countries went without. Under the Pandemic Accord, member states agreed that 10% of the production of any new drug or vaccine would go to the WHO, which would in turn dole out the doses more equitably to countries based on need. The accord creates a standardized system for countries to share samples and learn from new infectious agents more easily, which could speed development of vaccines and treatments. “Do you call it mismanagement if you try your best, identify weaknesses, and work to improve?” says Ghebreyesus. “It cannot be mismanagement.”

But seemingly, Trump’s biggest issue with the WHO is how much the U.S. pays in membership dues, which are the highest of the members. “The U.S. is complaining they are high, and we agree,” says Ghebreyesus. “And the surprising part is that we want the U.S. to pay less, so our interests are aligned. We don’t want to depend on a few traditional donors, including the U.S.” While member states pay dues calculated from a number of factors including their economic stability, some, including the U.S, contribute additional funds voluntarily. From 2022 to 2023, for example, the U.S.’s dues were $218 million, but it added $1.02 billion in voluntary donations. When he became director-general, Ghebreyesus anticipated the danger of relying on a handful of major donors, so he asked the 194 member states to gradually increase their dues to account for about 50%, rather than 20%, of the WHO’s budget by 2030, to which they agreed.

That base would mean the organization wouldn’t be overly dependent on the generosity of a few. “If we rely on a few traditional donors, they will tend to dictate,” he says. “And that denies the WHO independence.” The WHO isn’t alone with this scenario, as the U.S. is the largest donor overall to the U.N., contributing more than a quarter of its budget for humanitarian, peacekeeping, and economic and social development programs—which Trump has also signalled he would review, accusing the U.N. of being ineffective in addressing conflicts and social instability around the world.

As much of a shock as the U.S.’s financial actions have been to the global health community, Ghebreyesus—ever glass-half-full—also sees the events of the past few months as a catalyst to address the issue of aid dependence. “As an African, this is a good opportunity to focus on self-reliance,” he says. “What we need is fair trade, jobs, and development that is self-sustaining. It’s embarrassing to live on handouts from somebody—it’s not right. I see what President Trump has done as an opportunity for all of the developing world, to change the mindset of aid dependency, in the same way I see this as an opportunity for WHO to make us more empowered.”

***

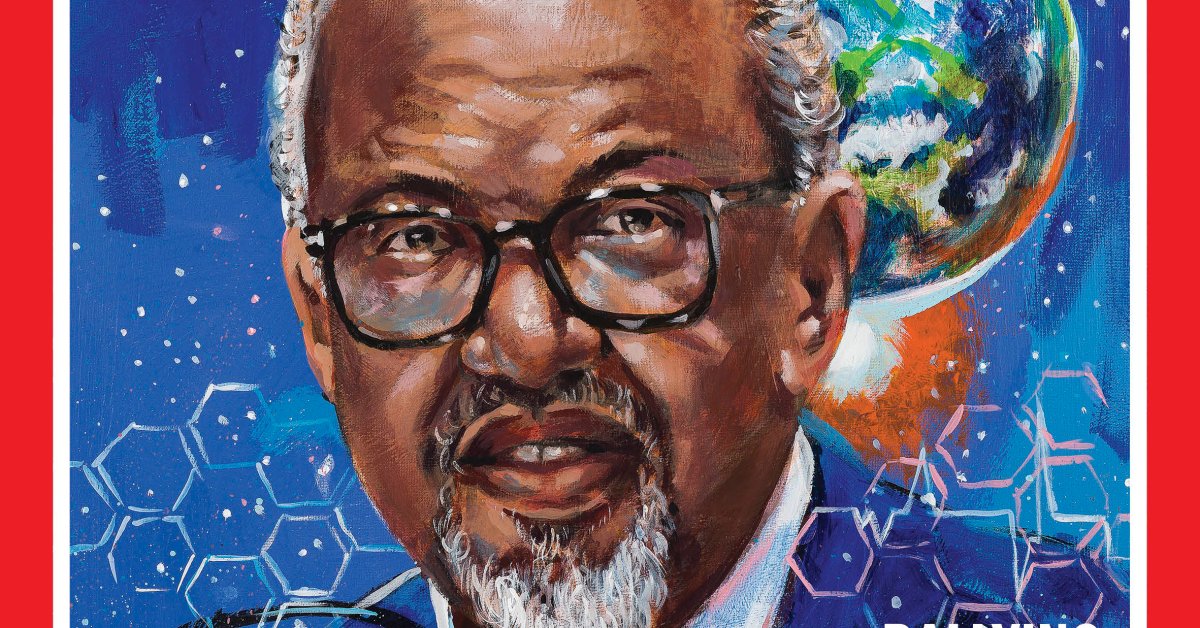

Ghebreyesus is the first director general to hail from Africa, and also the first without a medical degree. He was born in Asmara, Eritrea, before the country became independent and was still part of Ethiopia. His early exposure to violence and conflict from the civil unrest in the area, as well as tragic experiences with infectious diseases, shaped his desire to find, and do good, in the world. When his younger brother was around three, he died of what Ghebreyesus now believes was measles—a preventable childhood disease. He remembers his mother ushering him and his siblings under the bed, and piling additional mattresses on top, hoping that the bulk would stop any bullets from reaching them. “Of course, if a mortar hit, the entire house would be destroyed,” he says, “but that’s a mother’s intuition.”

He studied biology at the University of Asmara and earned a scholarship, sponsored by the WHO, to get a master’s degree at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “I would never have expected that someone who earned a WHO scholarship would one day be its head,” he says.

His work in combating malaria in Ethiopia elevated him to the position of Minister of Health, where he first demonstrated a penchant for grassroots strategies for promoting health. He championed a community-based program of mostly women to educate and dispense much-needed health care services to lower maternal and child mortality rates by about 60%. He then shifted to Minister of Foreign Affairs, where he honed his skills as an effective negotiator, and began building the network of connections with leaders in not just global health but politics as well, which continues to serve him in his current role at WHO.

Ghebreyesus thrives on social contact—he regularly posts on social media, sharing personal glimpses of his life with his children and four grandchildren to promote messages about vaccination—and has a unique ability to connect on a personal level, be it with a head of state or a cholera patient. Rather than whisking him away after meetings or even press conferences with journalists, his staff know to cushion his appointments with an additional half an hour or so. He holds weekly open-door sessions and asks all of his executives to do the same so anyone in the organization can bring them complaints, ideas, or problems.

That’s what he wishes Trump would have done—talk to him. “If someone is open to change, you don’t use that as a reason to leave,” he says. “If that’s your issue, then it’s better to stay and help implement those changes.”

***

Ghebreyesus does not relish this part of his job—cutting staff to try to make up for lost funds—but it must be done. When staff attempt to make the case for keeping a specific employee, Ghebreyesus stops the discussion, reminding them to focus first on the functions people perform at the organization rather than on individuals. It’s what Ghebreyesus sees as a more “humane” way of reducing staff costs, but the uncertainty still takes a toll. Since the executive order, the lunch crowd at the company cafeteria has thinned out as more people choose to work remotely, and those who are there can’t avoid the anxiety that overshadows their workdays. “There is a lot of uncertainty, and that’s hard for morale,”” says one employee who has spent more than a decade at WHO working in health workforce deployment.

Ghebreyesus hopes to save some jobs by moving people to regional or country offices, where the cost of living is lower than in Geneva and salary cuts wouldn’t hurt as much. The polio program could move to Cairo, and those working on traditional medicine to India, which has a strong legacy of supporting these practices. (A memo leaked from the U.N. in May proposed a similar move, relocating staff from New York to its offices in Rome or Nairobi.) He’s also hoping that a good number of people might choose to take early retirement. So far, Ghebreyesus has shrunk the number of WHO departments from 76 to 35, and pared program divisions from 10 to four: health promotion, disease prevention, and control; health systems; health emergency preparedness and response; and business operations.

The change also reflects a resetting of WHO’s activities back to services only it can provide. “We are happy to give away many of the things we do for other agencies or countries to do, and sunset things,” says Ghebreyesus. Some of this may include programs on chronic diseases like diabetes or obesity; Ministries of Health could oversee those while the WHO would provide the broad guidance and expertise that countries use to build and sustain their own programs. The WHO, for example, reviews new drugs or vaccines to determine their safety and efficacy and issues a pre-qualification that serves as a green light for countries that can’t conduct these reviews themselves. It’s an essential role that helps to distribute new medicines, like the COVID-19 vaccines, more quickly and equitably. “They are absolutely the only body that can do that effectively,” says Jha.

As part of the aid worker community that rushes in during health emergencies, Dr. Maria Guevara, international medical secretary at Doctors Without Borders, also hopes to see the WHO strengthen its voice in support of health workers around the world. “We believe WHO and ministries of health are the guardians of health care and access to health care, and should be the biggest voices for protecting them,” she says. “One of the things we’ve had deep and confrontational discussion with [the WHO] about is pushing for peace as a right, just as health is a right, and both should be of equal value.”

While Trump’s method may have been more abrupt and painful than it could have been, Ghebreyesus says he is now focusing on finding common ground. “I appreciate that Trump is Trump,” he says. “He is open, candid and speaks his mind. World leaders should speak their mind like him; be straight. And I also appreciate his efforts now to address [military] conflicts peacefully. You’ve heard me say many times that peace is the best medicine. He and I agree on that. We have many differences, but we agree on that.”

And he says he is optimistic that the U.S. will return to the WHO. “I still believe in that,” he says. “There is no reason to stay away, to be honest. No good reason.”