Primal Scream meet the Glasgow roar once again in a homecoming set that evoked the cinematic elements of their wide-ranging and ever-relevant discography.

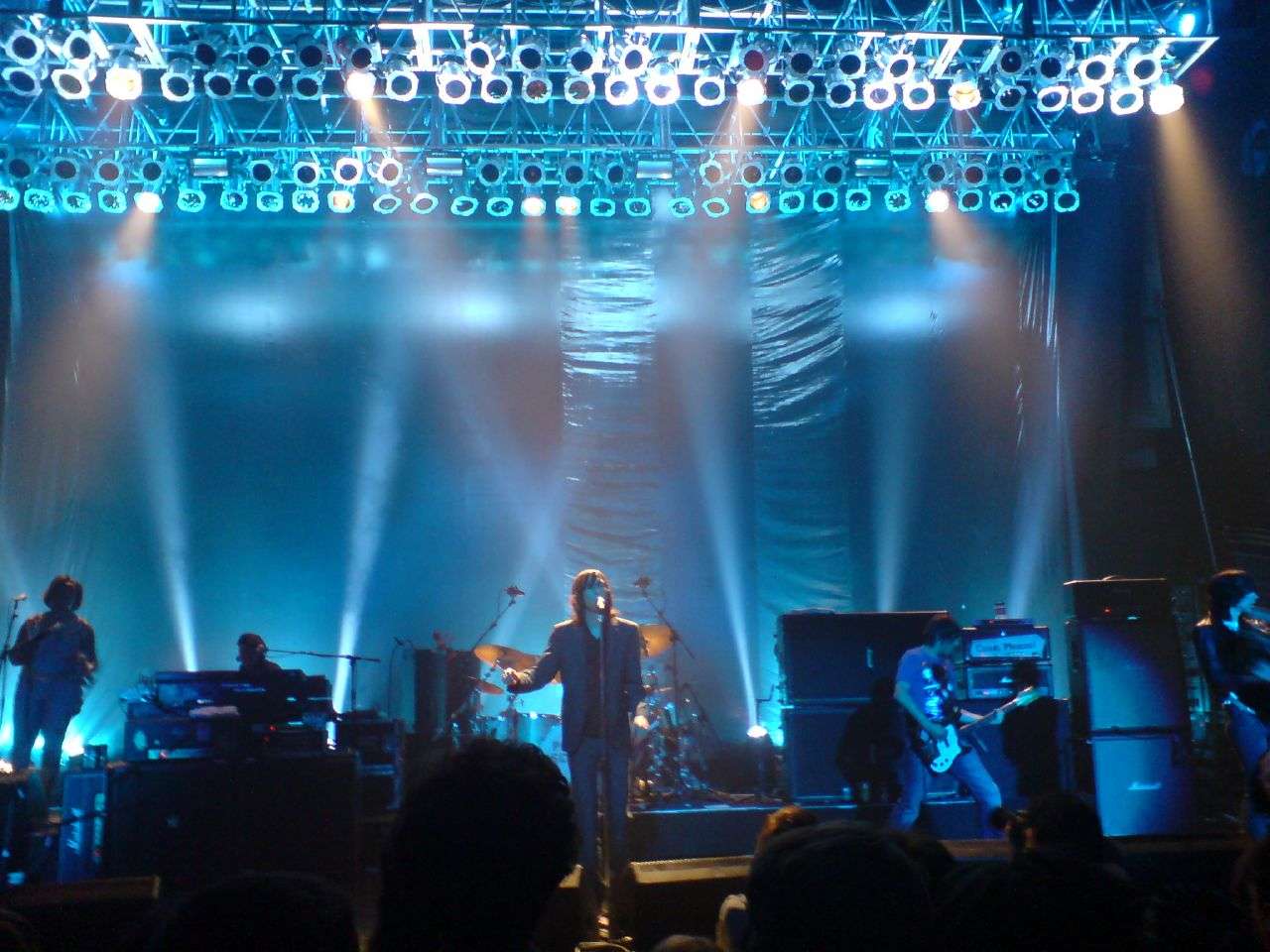

Eclectic is a nigh-inescapable term when discussing bands that have been around as long as Primal Scream, yet it’s the only proper way to describe Bobby Gillespie and Co’s return to Glasgow on the last of a two-night stint at the city’s O2 Academy. Their set was prefaced by a similarly genre-defying opener in Baxter Dury, who towed the line between industrious and industrial whilst shifting from mellow jungle to acid disco. Characterising this shift was an ever-increasing tempo firmly underpinned by Dury’s trademark abrasive vocals, bolstering drumbeats and a bassline that could be felt reverberating through the floor, alongside the footsteps of a crowd gradually beginning to fill the sold-out venue. Such movement matched the on-stage projection of Dury’s logo, a figure taking a right step forward, giving the illusion it was becoming three-dimensional, as if to meet the growing audience halfway across the increasingly club-like dancefloor. However, for all its gathered momentum, the opening set had a relatively nonchalant close. Not anti-climatical more than cliffhanger-esque as the band subtly departed, house lights remained off for a noticeable moment whilst tension lingered and ear-drums adjusted, blue-tinted strobes illuminating the ever-practical fluorescent tape demarking the stage.

When the lights signalling the intermission eventually did come up, it was as if the New Bedford Cinema that used to inhabit the venue came to life. The red curtains hanging centrally on stage stood out as they hugged a 3:2 projector screen, evoking notions of vintage 35mm film amongst the piles of equipment scattered across the stage to accommodate a 12-piece band. If the opener acted as a trailer, the main event was approaching. Immediately after this thought, the lights blacked out again as Jackie DeShannon’s “What the World Needs Now” faded in over the speakers for the band to enter. Only then juxtaposed by Gillespie’s own entrance to the drum and bass of “Don’t Fight It Feel It”, as he emerged in a white-clad suit that absorbed the surrounding red lights, alongside hues of the viscerally psychedelic visuals now behind him. Within these theatrical moments are what Primal Scream is all about, the mushroom cloud of a nuclear explosion backing “Love Insurrection”, and its 90’s-funk inspired main riff from the new record, Come Ahead.

Much like the title implies, the newer songs especially showcased a provocative nature that also feels inherent to Primal Scream, boosted by the full accompaniment including backing singers and a live flautist. Many bands run through their first few numbers concurrently, but Gillespie was content taking a minute to get re-acquainted with the hometown crowd. “Can we hear Glasgow?”. We can certainly feel it, just like a psychedelic trip before some of the more rock-infused tunes are brought out. The set begins to hit a stride at this point, instigated by “Deep Dark Waters”, with its rousing bassline and political message that again bears the trademarks of Primal Scream. For all the musical style that has evolved over the years, and the crowd as eclectic as the mix of genres, some aspects are foundational. The new record takes on a crucial role as during “Innocent Money”, Gillespie pleaded with the audience and the pink floods provoking him, crooning over the microphone whilst guitarist Andrew Innes matches on his left. Similarly, “Heal Yourself” continued this inventive tonal reset, showing a tender side to some of the political awareness as well as the enduring importance of Glasgow to the band’s music – with the focus on homecomings running parallel with Gillespie and Innes’ current circumstances.

“I’m Losing More Than I’ll Ever Have” continued this introspective streak whilst moving backwards in discography to more familiar territory, all whilst evoking the idea of reaching out over the balcony to catch the fists being thrown into the air as the initially bluesy tempo began to ramp up. Alongside “Love Ain’t Enough”, it created a stop-gap between new and old as backing singers mixed with harder guitar licks to match the cinematic film quality shown by the quick cuts projected onto the screen. However, the most visceral usage of the projector was within “The Centre Cannot Hold”, backed by a visualiser mixed out of the band’s most recent music video, featuring a black-clad Gillespie backed by sprawling urban imagery – an empty liminal space created from Thamesmead Estate in south-east London, both claustrophobic and endless at the same time. It wasn’t long however, before the maracas came out for the anthemic “Loaded”, during which even the security couldn’t be dissuaded from swaying their hips, as the crowd jolted into life through built up angst, anticipation and seismic energy when the iconic piano intro and bagpipe drawl kicked in. In ways, the jostling crowd participation recalled aspects of The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil”, the repeated tonal “Woo Woo” from the crowd plastering a genuine smile on Gillespie’s face – and finally, the suit jacket came off.

Would the crowd across town at Andre Rieu in the Hydro be witnessing the same sense of stage presence? Probably not, one would think whilst trying to imagine which intricate notions the Johann Strauss Orchestra were going through – juxtaposing “Swastika Eyes” as it faded in to underscore the more immediate sets versatility. Like a smoking gun next to a loaded question as Innes was given time to interact with the now fully-invested crowd, informing a more rock-infused rendition of “Movin’ on Up”, which bore the weight and reputation of the Screamadelica-era logo looming over the band.

Beginning the encore, “Melancholy Man” presented yet another moment for Innes to take centre stage as the blue-hued closing guitar solo created another shrewd tonal reset, bringing intimacy back as the grandiose art-deco architecture of the venue came back into view. “Come Together” with its synth church organ-like opening only bolstered this thought, the wide scope of a ten-minute song that doesn’t outstay its welcome is a true rarity. “Rocks”, indomitably lit by white strobes and phone screens, lasted less than half the time of the more sprawling songs inclusive of a reprise, yet retained a sharp impact before the house floods came up to signal the end of the show. Conversely to the cliffhanger of Dury’s set earlier in the night, Gillespie lingered on stage for a minute after the rest of the band left to share a moment with the audience. If ever there was a minute symbolic of his nature as a frontman it’d be something like this, as guitar feedback swelled to create a claustrophobic sense of immediacy within the room and the question was asked from both sides – where do we go from here?