A portrait of Jonas Phillips. (Photo courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution and the American Jewish Historical Society)

A portrait of Jonas Phillips. (Photo courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution and the American Jewish Historical Society)

In the summer of 1776, Philadelphia was in the process of changing the course of history.

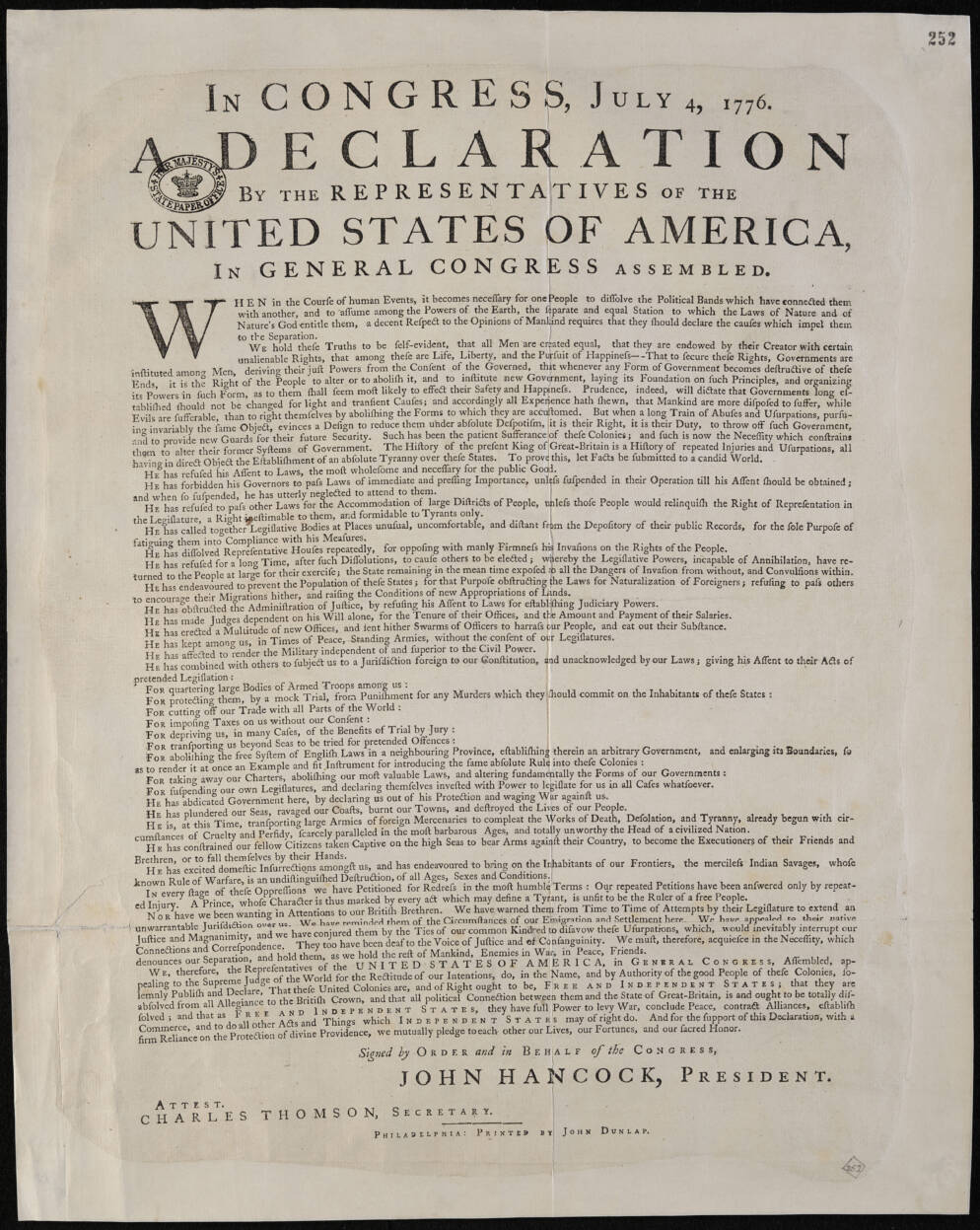

As most Americans know, July 4 of that year marked the Continental Congress’ adoption of the Declaration of Independence. The Continental Congress authorized a Philadelphia printer named John Dunlap to publish the first poster-size editions of the Declaration — known as broadsides — for circulation. Only 25 of those broadsides still exist today.

Now, one of those 25 original editions is coming home to Philadelphia, more specifically to the Museum of the American Revolution — and it has a Jewish connection.

Jonas Phillips was a Jewish business owner in Philly who had a shop on Market Street near the printing office where Dunlap created the broadsides. On July 28, 1776, he folded one of them up, enclosing it in a letter and sending it to a contact in Europe alongside a Yiddish note that was meant to conceal the significance of the artifact, as the British could of course more easily detect English.

That package was intercepted by the redcoats. Now, 249 years later, it is returning to Philadelphia to be displayed at the museum. Phillips’ story is an American one, and a Jewish one, too, said Matthew Skic, director of collections and exhibitions at the Museum of the American Revolution.

The Dunlap Broadside. (Photo courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution and the National Archives of the United Kingdom)

The Dunlap Broadside. (Photo courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution and the National Archives of the United Kingdom)

“Phillips is a person who was not only living in Philadelphia during this revolutionary moment, but actively contributing to the revolutionary cause. He was one of a small but growing community of Jewish men and women here, and he was a member of Mikveh Israel and a leader there,” Skic said. “He was active as a merchant in the city, and he was supportive of efforts to go against the Stamp Act and [other] British policies in America that were seen as a restriction on American rights and liberties.”

The Museum of the American Revolution will run a special exhibition on the Declaration, its journey to completion and its impact throughout the United States and world since then from Oct. 18, 2025, to Jan. 3, 2027, in honor of the United States’ 250th anniversary next year. Called “The Declaration’s Journey,” that exhibit will include the original contents of the parcel that Phillips sent to Amsterdam, which includes his Yiddish letter, the Dunlap printing and a bill of exchange for his mother. These items are on loan from the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

Phillips is an important figure in Philadelphian Jewish history, and his inclusion in this exhibit is important to telling the whole story of the city’s involvement in the birth of the country. His work on behalf of the fledgling nation continued after the Declaration was signed, as he joined a committee of Jewish leaders in Philadelphia and New York who began a review of state constitutions and the liberties that they protected.

That review called into question a Pennsylvania policy that required candidates for public office to swear that they believed in the Old Testament and New Testament.

“That effectively barred any Jewish person from serving in government office in Pennsylvania. And so Phillips and others actually petitioned the Pennsylvania government; they even petitioned the Constitutional Convention, which was convening in Philadelphia in 1787, and asked for this to be revised,” Skic said. “Pennsylvania [did] change its constitution in 1790 to get rid of that part of its requirement for office.”

That change is still relevant today. The current governor of Pennsylvania, Josh Shapiro, is Jewish.

Emily Sneff is a guest curator and historian for “The Declaration’s Journey” and is responsible for “connecting the dots” between Phillips’ Yiddish letter and the broadside, according to the museum. She said that its inclusion is a fitting way to celebrate the country’s 250th birthday.

“I love that these artifacts will have a full-circle moment by returning to Philadelphia for the first time since 1776,” Sneff said. “Telling Jonas Phillips’ full story is something the Museum of the American Revolution is uniquely qualified to do, and introducing people who come to the museum to this uniquely Philadelphian story is a great starting point for the exhibition.”

Phillips and his descendants are very much woven into the history of the nation. Jonas Phillips’ grandson, Uriah Levy, is a legendary American naval officer who is credited with preserving Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello after it fell into disrepair. Today, the mansion in Charlottesville, Virginia, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“Levy happened to be a fan of Thomas Jefferson, and purchased and preserved Monticello after the Jefferson family,” Skic said. “It’s an interesting connection between Jefferson, the Declaration, Phillips and his grandson.”

The display at the Museum of the American Revolution will touch on a variety of subjects, but Jewish Philadelphians and Americans will be proud to know that one of their own is a part of it.

“The Jewish-American community in 1776 was small, and yet we will exhibit artifacts in ‘The Declaration’s Journey’ that speak to their experience,” Skic said. “Telling Phillips’ story — that of an American immigrant, business owner and family man who still had an impact on the Declaration’s journey — builds historical relatability and empathy in modern audiences. It is a story that shortens the gap between 1776 and today.”