By Eddie McCoven | Cronkite News

PHOENIX — Ending the spread of HIV in Arizona may become more difficult if federal funding is cut or eliminated.

Phoenix is one of many cities that are a part of the Fast Track Cities initiative, an effort to combine local resources and leadership to end new HIV infections by 2030.

Angel Algarin, a professor and researcher with the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation at Arizona State University, says the goal may now be unattainable.

“I think the 2030 goal is a lofty goal,” Algarin said, “particularly with the federal cuts that are occurring.”

The Trump administration has eliminated some grants aimed at HIV education and prevention and cut funding at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Further cuts are being proposed, according to the HIV+HEP Policy Institute, including eliminating portions of the Ryan White Program, which was enacted by Congress in 1990 in memory of an Indiana teenager who contracted HIV through a blood transfusion.

Maricopa County receives more than $12 million in federal funding for the local Ryan White Program, which offers free and low-cost medical and support services to eligible people living with HIV in Maricopa and Pinal counties. The Positively You campaign is one of the county’s efforts to make sure those living with HIV receive treatment and services they need.

During a recent webinar with the city of Phoenix, Maricopa County Senior Health Educator Kate Thomas said any decreases in funding would slow down the work the county and city are doing.

“Less funds for fewer services mean less results,” Thomas said.

The Phoenix Fast Track Cities program has seen a 75% reduction in new HIV infections, with the goal of a 90% reduction by 2030, Thomas said. However, Arizona recorded a 20% increase in new HIV infections in 2022.

As of 2022, there were 19,894 people living with HIV in the state, according to the most recent data available from the Arizona Department of Health Services. Of those, 13,611 lived in Maricopa County.

Algarin says while the Phoenix area is not a bastion of liberalism like California or New York, there is less homophobia and other stigma compared to other areas in Arizona, especially for young gay and bisexual men who relocate from the Midwest. Better access to health care may also account for a larger population living with HIV in Maricopa County.

“You’re not going to a rural hospital to access HIV-related services,” he said.

Marcel Toro, an ambassador with the Positively You campaign, is living with HIV. During a recent webinar with the city of Phoenix, he said his health care experience in Yuma a decade ago, especially when he tested positive for HIV, wasn’t compassionate or competent.

“The nurse says, ‘Yes, you have the AIDS,’” Toro said. “Not HIV. He said, I ‘have the AIDS.’ And I was just sitting there in shock.”

Toro saw a doctor the following week.

“He was very cold, maybe like a 10-minute conversation,” Toro said.

Two months later, the doctor said Toro’s white blood cell count remained the same, meaning he must have been taking medication. But Toro had never been prescribed any HIV treatment.

“A lot of people would be discouraged at that point,” he said. “The system (is) failing them so much. But I thankfully … I had a very good support system.”

Toro said he leaned on his friends, especially one who worked in health care in California.

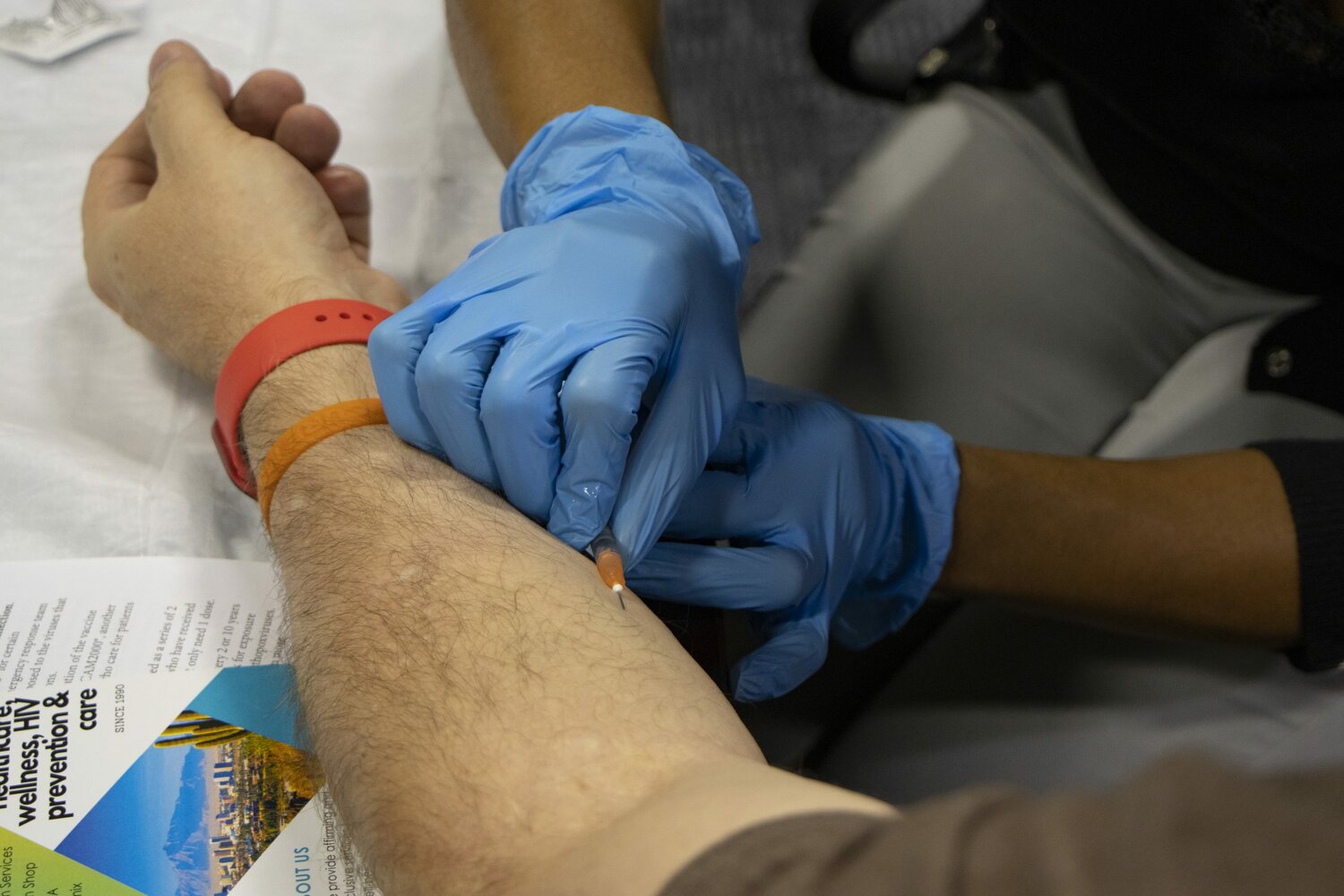

One of the breakthroughs in HIV prevention was the Food and Drug Administration’s 2012 approval of a pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) drug called Truvada. Since then, other pills, such as Descovy, have also been approved. The daily pill is proven to be extremely effective in preventing the spread of HIV.

Thomas says despite the recent advancements, persons of color are not taking advantage of treatment options as much as their white counterparts, with Hispanics making up the majority of new infections.

“We’re seeing a lot of gay white men on PrEP, but we don’t see the same uptake of PrEP in other populations,” he said.

Health care professions still have a lot of work to do to reach vulnerable populations, especially with people under 35, Thomas said.

“Latino communities continue to see increases in new HIV infections, and are disproportionately affected by HIV in comparison to their white counterparts,” Algarin said.

Algarin is working on a research project studying the association between social stigma and methamphetamine use among Latino men who have sex with men and how this affects adherence to a PrEP regiment.

Algarin said with federal funding cuts, along with what he calls the historic underfunding of public health in Arizona, more resources need to be allocated to slow the spread of HIV.

“I feel like people, when they’re talking about HIV, they think of it as something in the past,” he said. “No, this is something that is very, very present, and it continues to grow in states like Arizona.”