Our Grandpa died in the spring of 2020. It happened suddenly and unexpectedly; one moment he was in the world, the next he was on a ventilator in the hospital, and soon he joined the wave of people whose lives were brought to an end by COVID-19 that spring. He was 91, had lived a long life, with its full share of challenges and hardships, resilience, love, overcoming. He had been born in 1928, a world away from New Jersey, in a place now called South Korea.

A few weeks after Grandpa passed, our Grandma fervently wrote down almost 50 pages in Hangul on a yellow notepad. She’d produced a full recounting of their lives together. Those pages shone with all the emotion of her loss, trembled with an earthquake’s tremor, but what they had achieved together — the life they had built through and upon adversity — was a beautiful triumph.

We’d grown up listening to each of our grandparents’ retellings with interest and awe. Their lives were almost like folk tales or legends, seemed to come from another time, one infinitely far from us. Like so many Koreans of their generation, our grandparents were deeply shaped by history. We hear these words: colonization, civil war, poverty, loss, immigration. But do we know their meanings as our grandparents knew them?

The Riews’ grandparents in an old photo.

Courtesy of Julia Riew and Brad Riew

They met during the 1940s, when Korea was under Japanese occupation. At that time, the Korean language, customs and folk songs were all illegal due to Japanese state policy, and they lived under an environment of constant surveillance. They met as teenagers and fell in love — but because Grandpa was poor, with equally poor life prospects, while Grandma came from wealth, her parents did not approve. They were forbidden from seeing each other. And when Grandma deliberately refused to meet her parents’ preferred match, she was placed under house arrest as punishment. Nevertheless, they would sneak out to see each other at night, slipping each other love letters through intermediaries.

In those years, political turmoil swept through the Korean peninsula with a casual cruelty, upending lives. After the Japanese government decreed a ban on Korean and Western-style clothing, our great-Grandpa’s prosperous tailor shop suddenly went out of business. Grandpa’s dad came under extraordinary stress and later died of a stroke — which, by Korean custom, left Grandpa, at only 21 years old, the head of his family of seven, responsible for feeding his mother and younger siblings.

With that immense burden on his shoulders, Grandpa took on three jobs while somehow finding the time to attend Seoul National University. He also joined a student resistance movement for Korea’s liberation, all the while trying to save up enough money to marry Grandma. Meanwhile, Grandma worked as a teacher — until her family swept her away to the countryside with no way to inform Grandpa where they’d gone. Yet, they stumbled upon each other again through miraculous luck, nearly a year later in a small fishing village.

Their forbidden romance blossomed — then grew through the harrowing years into a deep, unbreakable bond that lasted through the war and the loss of their first child.

As sensational as our grandparents’ lives might sound, they were also typical for Koreans of their generation. They were ordinary heroes whose inventiveness, courage, dedication and hope carried them through extraordinary challenges and hardships. They never gave up on their insistence that, above all, they would survive. Their love for each other and their belief that such a better life was possible carried them through.

A photo from Brad and Julia’s childhood.

Courtesy of Julia Riew and Brad Riew

In the months after Grandpa passed, the importance of understanding our family history came to take on a new urgency; as third-generation Korean Americans who grew up in Missouri, we had fewer and fewer connections in Korea. Anyone who comes from an immigrant family understands how quickly our heritage can be lost and the past forgotten. When someone dies, their memories often die with them.

After we read through Grandma’s story, we scoured our archives until we found an email that he’d sent us in 2016, one of his recountings of his and Grandma’s love story in the 1940’s under Japanese imperialism. With it, he sent the following request: “Could you make up a fictional story?”

An email to Julia and Brad from their grandfather.

Courtesy of Julia Riew and Brad Riew

Soon after, the two of us began co-writing The Last Tiger.

For us, Young Adult Fantasy offers an accessible window into stories about suffering, oppression, love, and freedom, a way to mix whimsy with politics, emotion, and spirituality — to make entertainment and education two sides of the same coin, and to engage readers, perhaps stimulating their own opinions and ideas about human nature outside the context of the world as we think we know it.

In our novel, Grandpa and Grandma became Seung, a servant yearning to rise above his station, and Eunji, a noblewoman seeking to escape her supposed destiny. Colonial Korea became The Tiger Colonies. And the suppressed culture of the Korean people manifested into our world as Tiger ki — a spirit-endowed magic that allows its beholder to harness the inner power of emotion and memory.

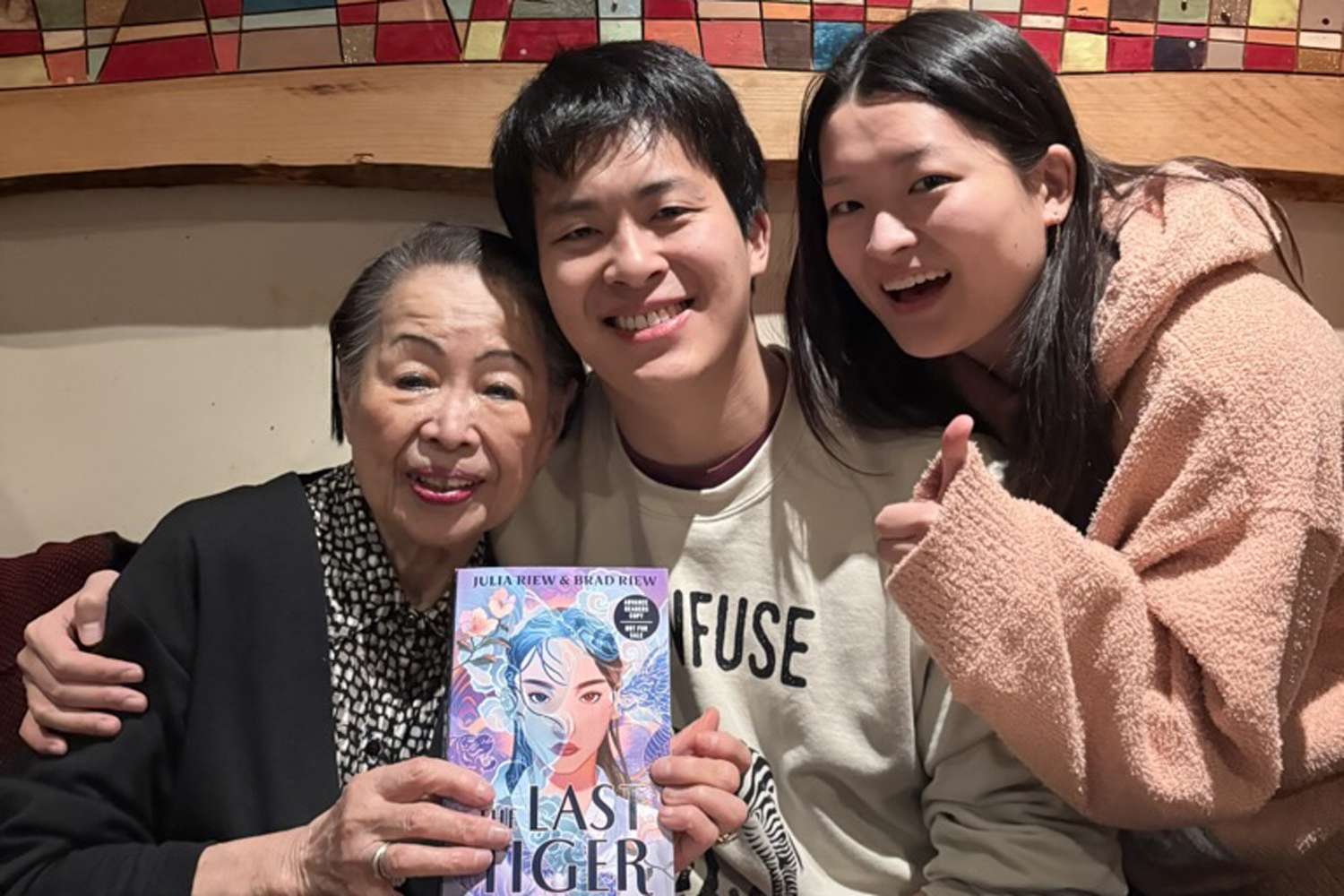

‘The Last Tiger’ by Julia and Brad Riew.

Penguin Random House

We chose to embark on this project so that the events of yesterday could carry meaning in the present for a new generation. When we look out into the world, we feel the echo in our bones of the storms our forebears once endured. When we listen to those around us, we hear confusion, fear — the struggle to understand our own moment in history.

It’s natural to feel powerless in dark times. To feel dread, or to not know where to look to find hope. And yet, for us, the memory of our ancestors’ strength and courage during times even more trying than ours is a grounding force. It gives us context; it helps us remember the fortitude inside us, and make sense out of confusion. It helps point to a way forward.

We know that young people are growing up into a world that will bring challenges and change, much of it disruptive. We know we will continue to experience oppression and adversity. And yet, none of us are alone. Our ancestors stand behind us at all times, their hands on our shoulders, reminding us that we, too, can be strong. We take inspiration from them, remembering how they met their moment — and with their words in hand, maybe we can also meet ours.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

The Last Tiger by Brad and Julia Riew is on sale now, wherever books are sold.