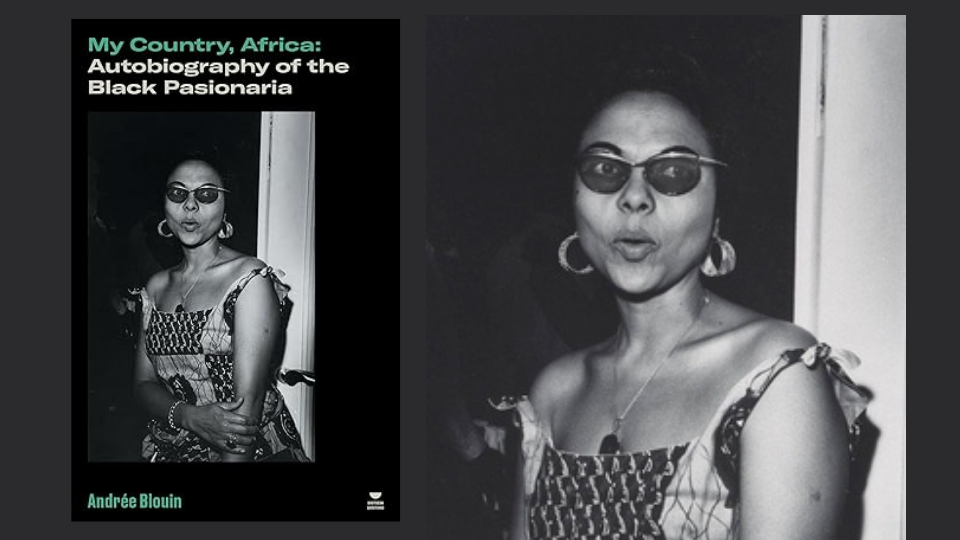

Andrée Blouin pictured right, cover of ‘My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria,’ left

Andrée Blouin was a freedom fighter. She is most well-known for her role in campaigning to build support in the Belgian Congo for its independence vote in 1959 and mobilizing thousands of Congolese women to the cause. She had been an advisor to Sékou Touré, President of Guinea, a former French colony that had voted for independence in 1958. Subsequently, she accepted a role as “chief of protocol” for Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba after the formation of his government in 1960. After the Belgian-orchestrated coup deposed and murdered Lumumba, Blouin was forced into exile. This book documents her life and political struggles.

Blouin was born in 1921 in Bessou, a remote rural village approximately fifty miles from Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic. Called Oubangui-Chari before independence, Blouin’s home country, a territorial portion of French Equatorial Africa, formed a part of the region that, before the 1958 independence vote, included the countries now known as the Congo, Gabon, and Chad. These countries had been colonized by France since 1910, in close collaboration with monopoly mining corporations. A sustained policy of extreme labor exploitation, violent repression of African organizing, intense taxation policies, and all sustained by racist segregation policies, conditioned the world into which Blouin would be born.

Blouin was born to a white father and a Black mother. Her father has “purchased” her mother, the twelve-year-old Josephine, in a traditional arranged wedding (never legally recognized) and fathered Andrée with her. While Blouin, later in the book and her life, denounces the practice of supplying a family with a dowry in exchange for an arranged marriage to pre-teen girls as a reprehensible form of child rape, she never directly condemns her father’s similar actions. While she denounces the racist system that denied her a real family and forced her to live apart from her mother for most of her childhood, Blouin emphasizes her attempts to understand and reconcile with her father. Like most of his European counterparts, her father refused to acknowledge Andrée and denied her access to the legal protections provided by taking his name. Eventually, she forgave him for abandoning her to an orphanage designed to house métisse (biracial) girls, but she never accepts or condones the racist, colonial system that created such an arrangement.

At the Catholic Church-run “orphanage” for biracial girls in Brazzaville, Blouin is forced to survive on meager meals, where “hunger was a constant companion.” She and the other girls were forced to labor as seamstresses, selling embroidered decorative items. The proceeds kept the nuns in good stead. The nuns used violence and threats along with psychological blackmail to punish the girls. Their whole existence, as Blouin writes, was premised on “the crime of being born of a white father and a black mother.” They bore the supposed sin of their parents, and the nuns taught them to always feel shame for it. Any act of willfulness deepened their guilt and shame. Blouin sees in the orphanage’s existence proof of the fact that the “racism on which the colonial system was built had failed.” If it was meant to be proof of European charity and civilization, its brutalities showed Europeans offered little in the way of social progress. It was a “waste bin for waste products,” she writes.

Surrounded by the orphanage’s high walls and deeply ensconced in the church’s doctrine of guilt and racial sin, Blouin still dreamt of freedom and observed that “black people suffered because they were black.” Around the end of 1928 and 1929, Blouin and her companions happened to see a procession of Black prisoners who were dragged past the gates of the orphanage. She recalls that despite being enchained and tortured, the men demanded access to French citizenship rights. Only later did she learn the men may have been part of a major uprising against the French system of forced labor and taxation that had swept through the colonies, including in her home country of Oubangi-Chari. An article from the same year in The Negro Worker, the periodical published by the Communist International’s International Trade Union Committee for Black Workers, documented the political struggle. French forced labor schemes to build a colony-wide railroad system led to the deaths of millions of the region’s inhabitants. The French government collaborated with monopoly capitalist firms to brutalize African workers for massive profits.

Blouin describes how the men were marched through the city streets as a warning to others who might resist French domination. But for her, witnessing the event had the opposite effect. It showed her not only the horrors of the Europeans but also the courage of Black people who fought for freedom. Despite French repression, the struggles ultimately led in the late 1930s to the extension of citizenship rights in exchange for military service and to the biracial children of French men, including herself. “It only served to remind me,” she writes, “of how I had been torn away from my mother and deposited at the orphanage like a lost article.”

In her way, Blouin developed into what the nuns saw as a “shameless rebel.” She fought “the constant duel” within her between her “outrage” at frequent abuses and the nun’s teachings that she should accept the realities of a life given to her. Instead, she cultivated a habit of questioning this life and demanding answers for the contradictions she experienced, even when her approach earned her punishment and condemnations. Indeed, malnutrition and exposure to parasites and mosquitoes finally forced the nuns to take Blouin to a doctor, where the evidence of her treatment proves embarrassing to the colonial authorities. Despite warnings from the nuns to keep quiet, Blouin testified against the nuns, and an investigation compelled them to alter their treatment of the children. Later, as an older teenager, Blouin failed in a first attempt, along with two other girls, to flee the orphanage, having been caught after a citywide search for the fugitives.

Despite the brutalities of life with the nuns, they believed that the girls, who grew up in that institution, would stay close to the church and would even become nuns, with so few other opportunities available to them. Blouin describes her ultimate release from the orphanage at 17 as a “flight to a new life.” Initially, she lived with her mother in the segregated section of Brazzaville, earning a living as a seamstress primarily for European women. In this part of her life, Blouin experienced frequent attempts by European men to seduce her and to make her their mistress, while European women exploited her labor, often refusing to pay her an agreed amount for her sewing work. She was caught in a “colonial psychology” that deemed her worthless except to the extent that she would function as a sexual partner or a laboring subject. At this point in her life, Blouin joined resistance struggles with other Black women against racist segregation practices in Brazzaville, earning occasional threats of imprisonment.

Between the late 1930s and the late 1940s, Blouin had children with two European men. The first, a Belgian capitalist, refused to marry her despite sharing a household with her in Dima in the mineral-rich province of Kasai, Democratic Republic of Congo. At this time, Blouin saw the birth of her first child, Rita, as a metaphorical reflection of “the labor pangs and bloody birth of that country in its independence,” a struggle in which she would so significantly participate almost two decades later. After the father married a white woman and forced her into hiding, she saw the patterns of her father’s abuse of her mother being repeated, so she left that situation. A second relationship with a French man and a return to the French colony near Bangui resulted in another child named René. The family’s location in a rural part of the countryside exposed them constantly to mosquitoes and malaria, which proved disastrous for René. Blouin’s attempt to get quinine tablets to treat René’s illness was denied because a French law denied that life-saving medicine to Africans. Repeated appeals to the authorities to help her son were dismissed and were even accompanied by threats to punish her if she didn’t stop.

Without treatment, Rene tragically passed. Blouin identifies his death as a turning point in her life and thought about colonialism. She compared this experience to Jim Crow apartheid in the U.S. South, watching her son die in the hospital while, nearby, a white child received quinine and recovered a few days later. In her rage, she shouted at the colonial bureaucrat who refused her the medicine. “Cursed race!” she screamed. “Yours is an accursed race. Cursed authors of a murderous law. Child murder! You are murderers, murderers, all of you.” She added, “The death of my son politicized me as nothing else could.” These events led her to feel a closer identification with Africans, as, up to now, her upbringing, citizenship, and access to Europeans had made her feel somewhat detached from their experiences. But when the French colonial system killed her child, she developed a “clarity of vision” that ended the illusion. The colonial system was designed to deny humanity to Africans and “to keep blacks in submissive service to the whites.” “We who have been colonized,” she famously said, “can never forget.”

A third relationship with a French engineer changed her destiny. André Blouin took Andrée to Siguiri, Guinea, sometime in the early 1950s, where he was appointed to oversee mining operations for the French authorities. In Guinea in the late 1950s, Blouin connected with the Rassemblement démocratique africain (RDA), a political movement founded by trade union leader and future Guinean president, Sékou Touré. Her involvement in the campaign to mobilize votes for independence in the 1958 plebiscite led to close political relationships with Touré and other future African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah.

A chance meeting with Congolese political leaders Pierre Mulele and Antoine Gizenga, who would become officials in the country’s first independent government, drew her into the Democratic Republic of Congo’s fight for independence from the oppressive Belgian colonial system. The final chapters of My Country, Africa detail Blouin’s role in the Congolese independence campaign, which involved risking violent retaliation from the Belgian authorities. They trace the independence victory and describe the brutal manipulations by the Belgian government, now aligned with U.S. financial interests, to incite civil war and to destroy the first independent, democratically elected government under Patrice Lumumba. This portion of the book reads as both a political treatise and a gripping thriller.

Ultimately, Blouin, demonized by Belgian authorities as a “courtesan” to the African leaders and as a communist, was expelled from the DRC, and her family moved to Algiers, where they resided throughout much of the 1960s. Blouin explicitly denies having ever been a communist. Throughout the book, she emphasizes Pan-African unity against colonialism, including with center social forces who were inclined to posture as anti-communists. Her main political outlook seems to center around advocacy of the broadest possible unity of the people and the main social forces against colonialism and in the work of nation-building in the post-independence setting.

My Country, Africa, represents what the editors of this new edition call “a map of African national liberation.” Thus, careful readers should be prepared with a digital map of countries such as the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, and Senegal. Also a must is the reader’s ability to locate major cities like Bangui, Brazzaville, Conakry, Dakar, Siguiri, and Algiers, as well as to clearly distinguish the transition in names after independence from Leopoldville to Kinshasa, Belgian Congo to Democratic Republic of Congo, and Stanleyville to Kinshasa. A working knowledge of prominent African figures such as Sékou Touré, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Joseph Kasavubu, Antoine Gizenga, and Pierre Mulele is also helpful.

My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria

By Andrée Blouin

New York: Verso Books, 2025

ISBN: 978-1839768712

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

CONTRIBUTOR