Maybe it’s the success of HBO’s emergency room series, “The Pitt,” but Pittsburgh feels like it’s having a moment right now. Suddenly, everyone is grabbing Primanti’s sandwiches and wearing Steelers jackets. But the city has always provided the backdrop for books and tv and film. It’s not just the gritty atmosphere born out of a complicated industrial past, or the three rivers and 446 bridges that define the landscape; it’s not the aesthetic pleasure of the two “inclines,” cable cars that crawl up and down Mt. Washington, or the cinematic intrigue of the Fort Pitt tunnel, featured in the iconic scene at the end of “The Perks of Being a Wallflower,” to the tune of David Bowie’s “Heroes.”

The reason Pittsburgh is the perfect backdrop for drama is its relative modesty. It is modestly sized, and modestly priced, and modestly aspirational. Nobody arrives in hot pursuit of fame or fortune. It is neither East nor West. Also, not the Midwest. It doesn’t share the fraught obsessions or weirdness of the South. It’s not cold and desolate like the North. As Joseph O’Neill said in an interview about why he chose Pittsburgh as a setting for his most recent novel, Godwin, it’s “not on the way to anywhere.”

Pittsburgh is no tabula rasa—there’s too much history to argue it doesn’t have a culture all its own—but it does feel like a city that could be anything for any person, rich or poor, a place that is both always changing and hasn’t changed a lick in fifty years. It is an every-town that is the perfect place to come of age.

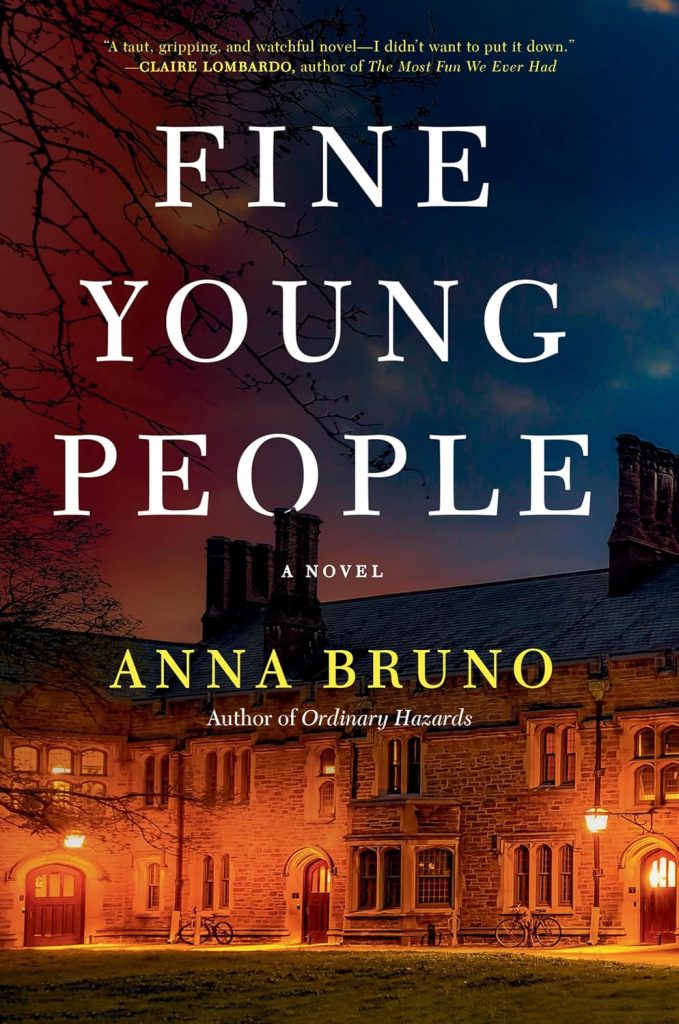

I set my sophomore novel, Fine Young People—about the mysterious death of a hockey player at a Catholic prep school—in Pittsburgh, because I couldn’t imagine high school anywhere else. While most of the action takes place on campus, the kids find their way to the Strip District, take a ride on the incline, and dance on the river-cruising Clipper Ship. They fall in love, and out of love, and eventually, they leave. Though some of them will come back. That’s the thing about Pittsburgh: I can always return to find that it’s still the place of my youth.

Here are seven books that show Pittsburgh is the best place to come of age—at any age.

The Mysteries of Pittsburgh by Michael Chabon

Chabon’s debut is the tragicomic coming-of-age of Art Bechstein, during the summer after he graduates from college. Art makes friends and lovers, exploring his sexual identity as he reckons with his mobster father’s sins. After meeting his buddy, Cleveland, at the boiler plant, which Art affectionately calls the Cloud Factory, they head out to collect illegal interest for Uncle Lenny, a local loan shark. It is on this journey that Art gets his first street lesson in economics, “the precise measurement of shit eating, it’s the science of misery.” Nothing captures the feeling of growing up quite like Art’s Museum of Real Life. He is a tourist in his own city, a spectator amused by the wretched circumstances of other people’s lives, until finally, he sees the world for what it is.

Emily, Alone by Stewart O’Nan

Somehow Stewart O’Nan managed to burrow deeply into the psyche of an old lady for Emily, Alone. There is no character in fiction who feels more real than Emily Maxwell. She reads the newspaper, cleans before the housekeeper arrives, and waits impatiently for thank you notes from her grandchildren.

As Emily traverses Pittsburgh in her cobalt-blue Subaru Outback, I found myself on Google maps, tracing her routes around my hometown. Her journey ends when she leaves the city to visit the rural Pennsylvania outpost where she grew up. There, she finds the house of her childhood, restored to its original white with forest-green shutters, and her mother’s hydrangeas in full bloom. For the first time, she doesn’t wish to distance herself from the child she once was, proving that nobody is ever too old to come of age. Fortunately, Emily will be back this fall in O’Nan’s newest book, Evensong.

The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

The Perks of Being a Wallflower is not the only YA novel set it Pittsburgh that was made into a big Hollywood movie, but it is the one most people think about. Through a series of letters, Charlie tells the story of his freshman year at a suburban Pittsburgh high school, culminating in a mental health crisis that stems from past trauma. The heaviest of topics, including violence and child abuse, are balanced with the hopeful sense that friendship can carry a young person through. Chbosky reminds us that only in youth can we feel “infinite,” and such intensity has the power to both save and destroy a teenager, maybe at the same time.

Chbosky and I grew up in the same suburb. Scenes from the film were shot in my neighborhood. Stewart O’Nan may be the bard of the city proper, but Chbosky understands growing up in the suburbs like no one else: the longing, the alienation, and the repose.

An American Childhood by Annie Dillard

In her most famous work, Dillard offers vignettes about growing up in Pittsburgh in the 1950s. The memoir is a celebration of books, curiosity, and pursuing one’s passion, and a reminder of the possibilities of childhood before helicopter parenting became a thing. Growing up, Dillard felt like she could fly. If the world were a kinder place, all children would feel that way. An American Childhood opens with an observation about memory. When everything else is gone, all the names and faces, what will be left is topology. This idea—that memory is continuously deformed by stretching, twisting and bending—is central to the coming-of-age narrative.

Brothers and Keepers by John Edgar Wideman

John Edgar Wideman’s memoir is so different from Annie Dillard’s, it might be surprising that they were written about the same city by two writers who were of the same generation, except for the fact that it’s not surprising at all. While Dillard explores the intellectual curiosities that her privilege affords, Wideman is forced to return to the reality that he was never able to escape, try as he might, when his brother shows up on his doorstep—literally and figuratively—on the run from the law. Brothers and Keepers interrogates punishment, not justice, because justice implies a balancing of the scales that is not America’s reality. And it is about the unbreakable bond of two brothers, despite being pulled in opposing directions by devasting individual choices and inescapable institutional forces.

These Violent Delights by Micah Nemerever

If Donna Tartt had set The Secret History in Pittsburgh and made it darker, it would be These Violent Delights. The central characters, Paul and Julian, are, in a word, terrible. They are terribly bright and terribly troubled and terribly in love, and they do terrible things to each other and the people around them. These Violent Delights is psychological suspense at its best. As the characters self-destruct, the reader can’t help but care for them because their motivations are rendered with such finesse.

In his Author’s Note, Nemerever cites Leopold and Loeb—the infamous University of Chicago duo that committed a thrill killing—as inspiration. His decision to move the terror to Pittsburgh takes advantage of the every-town vibe, and multiple references to the city’s early-70s pollution really set the mood.

Godwin by Joseph O’Neill

Pittsburgh isn’t the first setting that comes to mind for a workplace satire, but in O’Neill’s Godwin, it is Baby Bear’s bed for the technical writing co-op, The Group. The Group’s first clients are the city’s “countless medical-scientific entities,” which explains all the reader needs to know about post-industrial Pittsburgh. Told through an unlikely pair of narrators—Mark Wolfe and his boss, Lakesha Williams—the novel takes readers on Mark’s international journey to find the African soccer prodigy, Godwin. With humor and heart, Godwin manages to interrogate the dark side of international moneymaking. For Mark, it is a midlife coming-of-age, a reprieve from thwarted ambition and stagnation. As he says at the beginning of the novel, “Once in a million years, you push back. This was the day I pushed back.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.