Art

Maxwell Rabb

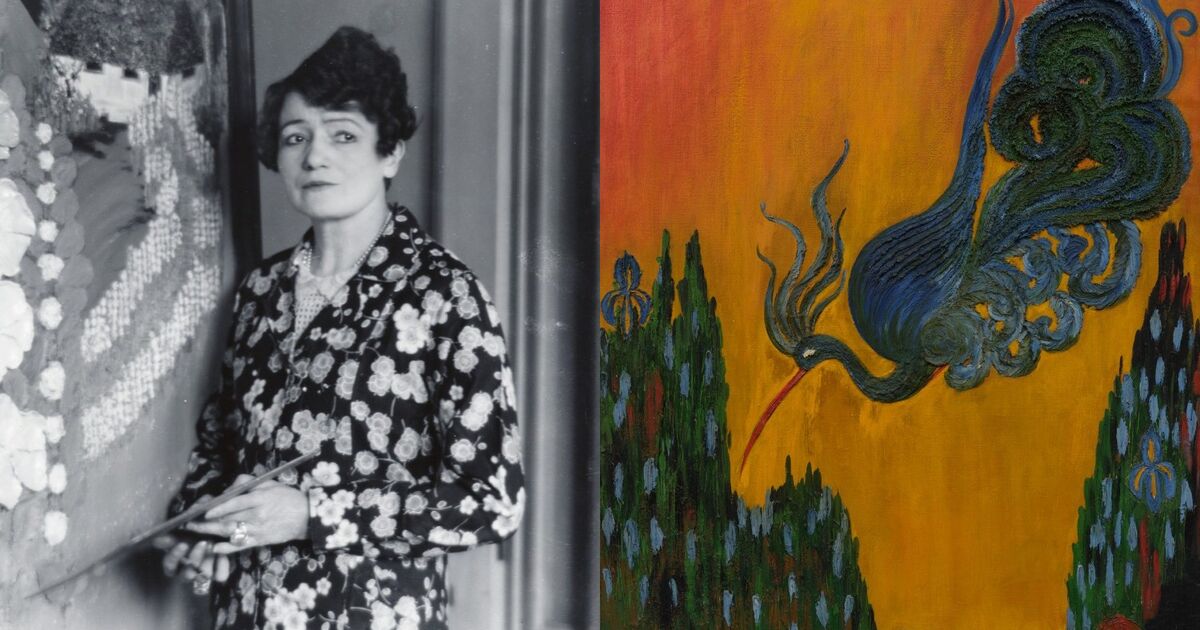

Portrait of Marian Spore Bush. Photo by Peter A. Judley & Son. Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum

Marian Spore Bush turned to spiritualism after the death of her mother. It was 1919, and, like many mourning Americans in the years after World War I, she picked up an Ouija board to cope. This foray into occult rituals was a new path for her—indeed, she had established a long and stable career as a dentist. But what began as a personal coping ritual soon took on larger dimensions and led to the artistic career that came to define her later life. Through the Ouija board, Spore Bush claimed she began receiving messages from a group of nonphysical entities she called “the People,” or simply “They,” who urged her to start making art. She recalled in her posthumously published autobiography that these spirits dictated everything from the paint colors she purchased to the subjects of her large-scale oil paintings.

This eccentric beginning resulted in a visionary body of work that has been forgotten in the art historical canon. Now, Spore Bush’s paintings are the subject of “Life Afterlife: Works c. 1919–1945” at Karma in New York, on view through September 6th. The show is her first in nearly 80 years. Long overlooked, these doom-laden works are now being given a second life at a moment when institutions are increasingly attuned to women artists who worked outside the bounds of formal movements. “Marian Spore Bush didn’t go to art school, and she wasn’t copying anyone,” said Bob Nickas, curator of the show. “There was not even any financial motive for her in making art. It was a compulsion.” Reframing Spore Bush alongside figures like Hilma af Klint and Gertrude Abercrombie, “Life Afterlife” invites a reappraisal of this artist who, with no formal training, worked in solitude and under claimed spiritual guidance.

From dentistry to drawing

Marian Spore Bush, installation view of “Life Afterlife: Works c.1919–1945” at Karma, 2025. Courtesy of Karma.

Spore Bush was born in 1878 in Bay City, Michigan, where she later became the state’s first licensed woman dentist. By all accounts, she was respected in her field and financially independent. Nonetheless, after two decades as a respected dentist, she closed her practice at around the age of 40.

According to archival materials from her sister, Spore Bush never studied or even considered making art. That changed when she began receiving messages—first through a Ouija board, and later, directly—from what she described as spirits of dead artists, instructing her to draw, then paint.

Spore Bush traveled to Guam, where her brother was serving as governor general. There, in near-isolation, she started painting for the first time—initially, floral still lifes, rendered in oil paint on paper. But soon, these early works shifted. At some point between 1919 and 1922, prophetic figures appeared—robed, watchful, and often surrounded by baby animals, seen in Untitled (ca. 1920s), where a sage-like figure greets congregating animals. The compositions remained gentle, but Spore Bush’s symbolism grew heavier, hinting at a moral conviction characteristic of her later paintings.

The move to New York City

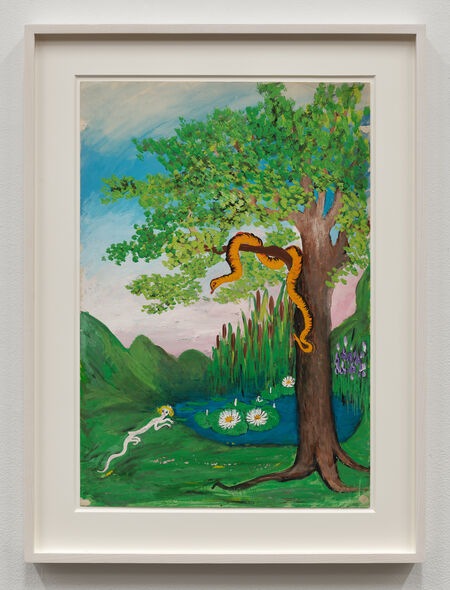

Marian Spore Bush, The Green Bird, c.1930. Courtesy of Karma.

Following her stint in Guam, Spore Bush relocated to New York and set up a studio in Greenwich Village. She threw herself into painting full-time, guided, she said, by the same voices that had first urged her to draw. Her early canvases were vivid and intuitive, marked by swirling forms and thick layers of paint that at times rose from the surface like low relief. For instance, The Green Bird (c. 1930), a painting of a descending bird floating above a lily pond against a fiery sky, features a thick impasto technique on the tail that makes the tail feathers appear almost sculptural.

Another shift occurred in the early 1930s, when Spore Bush’s colorful style gave way to stark black-and-white canvases. She claimed “the People” had warned her of impending war, and she responded by creating stark allegories of disaster. At the Karma show, across from The Green Bird, The Gaunt Bird of Famine (1933) shows a reaper-like bird with colossal white wings hovering over a lifeless cityscape, rendered in crude brushstrokes.

Spore Bush’s paintings became increasingly grim; However, her life took a different turn. During the Great Depression, she operated a breadline, a charity providing free food to people in the Bowery. The press dubbed her the “Angel of the Bowery,” and The New York Times referred to her as “Lady Bountiful.” Another worker at the breadline was her future husband, businessman Irving T. Bush, who would go on to support her painting career.

“It feels especially meaningful to show Marian’s work just a few blocks from where she ran her breadline on Second Ave,” Brendan Dugan, founder of Karma, told Artsy. “There’s something so charged and unexpected about [these paintings].”

Marian Spore Bush’s symbolic world

Marian Spore Bush, installation view of “Life Afterlife: Works c.1919–1945” at Karma, 2025. Courtesy of Karma.

In 1943, TIME magazine profiled Spore Bush to coincide with an exhibition at New York’s Grand Central Galleries, heralding the artist as a “prophetess.” Once World War II broke out, her work addressed the war more directly, in works like Hitler Meets God (1943), where the German leader, represented as a serpent, faces divine judgment. Unknown Soldiers (1943), meanwhile, features a flock of warships beyond a flock of birds.

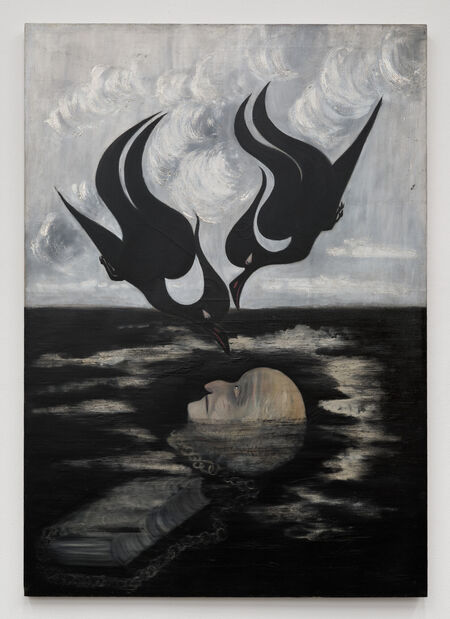

Her paintings often depict birds, which represent judgment or protection, a part of the rich symbolic world she built in her work. Many of these birds are rendered in grisaille, a painting technique using shades of gray. In The Pawn Broker (Three Vultures) (ca. 1933–34), two inquisitive vultures descend toward a man chained and drowning—a typical allegory of punishment for human hubris.

New recognition for Marian Spore Bush

Marian Spore Bush, Seascape, 1943. Courtesy of Karma.

Though she worked during the same years as the Surrealists, Spore Bush was allegedly unaware of their existence. Instead, she belongs in the company of spiritual modernists, often working alone, like af Klint, Agnes Pelton, and Paulina Peavy. Bob Nickas, curator of “Life Afterlife,” told Artsy, “The common ground [for these artists] is that art is a means of communicating and transcending.”

Spore Bush, according to her autobiography, was directed by “the People” to share a single message: “There is no death.” Some works read as apocalyptic, but others hint at salvation. For example, in Seascape (1943), a lone woman drifts on a piece of wreckage across a churning sea. Above her hovers a bird—elegant and white with an extended red beak—what might look like a gentle angel of death. Spore died in 1946, shortly after World War II ended.

“Life Afterlife” is aptly named. For an artist who believed so fiercely in the persistence of the soul, this posthumous recognition serves as a kind of resurrection—an earthly afterlife for someone who spent her life channeling the unknown. “She believed there was life after death. The fact that there is this show proves that. But it’s also a metaphor for art across all history,” said Nickas. “The artist lives on through their work.”

MR

Maxwell Rabb

Maxwell Rabb is Artsy’s Staff Writer.