AUSTIN — Texas lawmakers moved a notch closer in their quest to bar local governments from using public dollars on outside lobbyists Wednesday.

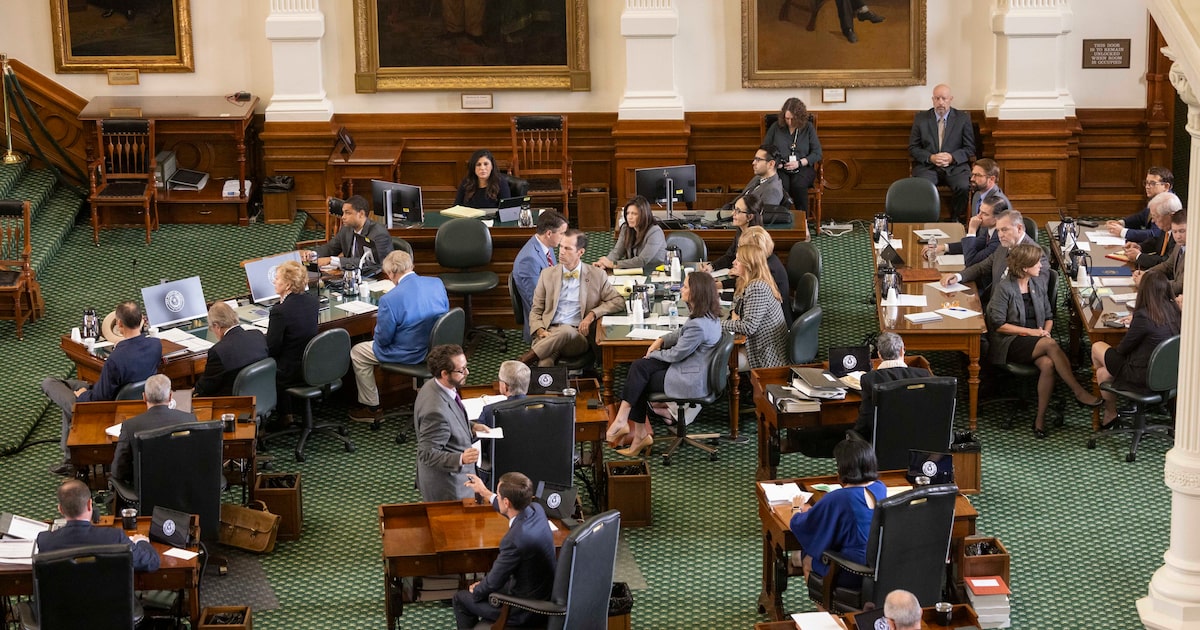

The GOP-dominated Texas Senate approved the bill on a 17-11 vote amid a debate that has largely focused on whether the state was reforming where taxpayer dollars are spent or whether it was eroding local influence.

“This bill grows the voice of our constituents, and money from the pockets of our taxpayers will no longer be taken by force and used to pay for lobbyists that undermine their interests,” said Sen. Mayes Middleton, R-Galveston, one of the bill’s authors.

Senate Bill 12, if signed into law, prevents cities, counties and school districts from hiring lobbyists or organizations they say are instrumental in navigating nearly 11,000 bills progressing through the legislature and getting essential state funding for projects. The legislation now goes to the Texas House for consideration.

Political Points

The bill would not impact private businesses and special interest groups that use their muscle and unlimited budgets to push policy. It also excludes law enforcement associations that hire lobbyists and charter schools, which are funded by public school dollars but run privately.

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick celebrated the bill’s passage and said Texans don’t want their tax dollars going to lobbying firms.

“I have consistently advocated for and prioritized banning this practice, which leeches off taxpayers to their detriment,” Patrick, a Republican, said in a statement after the vote. “Texans do not want their hard-earned money to be funneled into lobbyists’ pockets, who normally live outside their communities and do not advocate for their values. Texans expect their elected officials to advocate on their behalf, not outsource their voice to special interests who subvert them.”

Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, made ending the practice of taxpayer-funded lobbying by public entities a priority during the special session. Similar legislation has failed in several previous legislative sessions, including the one that concluded in June.

Those opposed to the practice, primarily conservative lawmakers, decry the reliance on outside lobbyists. Texas law already prohibits local governments and agencies from using state money to pay for lobbying, but advocates have long pushed for a ban on using any form of public funding.

Middleton took issue with local governments paying “middlemen” to fight “against things that our voters support,” like property tax reform and school choice.

The bill, he suggested, does not prohibit interest groups from assisting cities, counties and schools in tracking legislation and analyzing bills. It also would not prohibit elected officials or their staff from advocating for or against issues in Austin as long as they are not paid lobbyists.

Other conservative experts have raised concerns over Dallas’ use of public dollars for lobbying efforts on “the green agenda” for solar power and electric vehicles, along with diversity, equity and inclusion efforts.

But opponents who represent public schools and municipalities say the ban is a form of censorship that weakens their ability to influence policy, while businesses and special interests will continue pushing their priorities through lobbyists.

Local officials do not have the technical skillset or relationships the way lobbyists do, said Cal Jillson, a political science expert from Southern Methodist University.

These hired professionals have often historically worked for powerful political offices in the Legislature or in the governor’s office. Many are former elected officeholders themselves and have a deep working knowledge of the complicated and delicate legislative process.

Senators arguing against the bill said Wednesday it would hinder the ability of those entities to represent their own constituents in Austin.

“You want it to be an unfair fight,” Sen. Nathan Johnson, D-Dallas, said to Middleton. “A billionaire could throw a million dollars behind some lobbyists to try to get their way in this building, but the city couldn’t hire a lobbyist to be equally equipped on the issue.”

The impact, opponents say, will likely be felt the hardest on smaller, rural municipalities and school districts that may be located hundreds of miles away and have neither the time nor the resources to travel to Austin or hire an in-house lobbyist.

Dallas has spent $794,000 on state lobbyists over the past two years, and brought back $233 million in state appropriations since 1995, according to updated figures from city officials. These include millions of dollars for homeless services, $25 million for the new police academy, and money to restore structures in Fair Park.

James Quintero, policy director of Texas Public Policy Foundation, has questioned Dallas’ use of contract lobbyists while also maintaining an office of government affairs and employing a state legislative director, whose role is housed in the city attorney’s office.

In the current fiscal year, the city set aside $397,700 for outside state lobbyists, while budgeting more than $862,000 for its in-house government affairs staff. Meanwhile, the state legislative director in the city attorney’s office is paid $105,000 annually.