“In my own research on queer art and activism, I noticed that most accounts are myopically focused on New York City and, to a lesser extent, San Francisco,” says Schneider, 33, who has a master’s in art history from the University of Chicago. “So that became the angle of this project: There’s a gap here. There’s never been a museum exhibition that focused on queer art history in Chicago.”

“The show frames the city as a metropolitan sanctuary for queer people. You get an idea of what Chicago could become.”

— Jack Schneider, MCA assistant curator

Schneider selected more than 80 works, arranging them into five thematic categories that take viewers on quite a heady trip, one that doubles as a history lesson. In the Club section, for example, the late Luis Medina’s fetish photos from the early 1980s hit like pulse-pounding poppers. In Street, scathing editorial cartoons about the AIDS crisis by the late Danny Sotomayor are a burning shot of Fireball. In the concluding Utopia, Evanston native Edie Fake’s 21st-century drawings, blending real Illinois architecture with fantasy elements, provide a soothing sip of matcha.

An untitled sculpture from 2023 by Chiffon Thomas Photograph of the artwork: Karl Puchlik

An untitled sculpture from 2023 by Chiffon Thomas Photograph of the artwork: Karl Puchlik

The MCA leaned on its own collection but also borrowed work from many sources, including School of the Art Institute professor Mary Patten, who kept a personal archive of queer-activist memorabilia from the late ’80s and early ’90s.

Another pillar source: notable HIV/AIDS physician and researcher Daniel S. Berger, who in 2010 founded Iceberg Projects, a noncommercial gallery in Rogers Park that focuses on LGBTQ artists. He began collecting such works during the early years of the AIDS crisis: “I had many patients connected to the art world — artists, curators,” Berger recalls. “The topic of AIDS politics was always top of mind — we always talked about that — so art became very important to me. I felt the passion and strength in many of the works being created by queers around that time. It was also a really good distraction from the horrors I faced in the clinic. For me, collecting art is about activism. It gives attention not just to the artist but to the messages they’re putting out.”

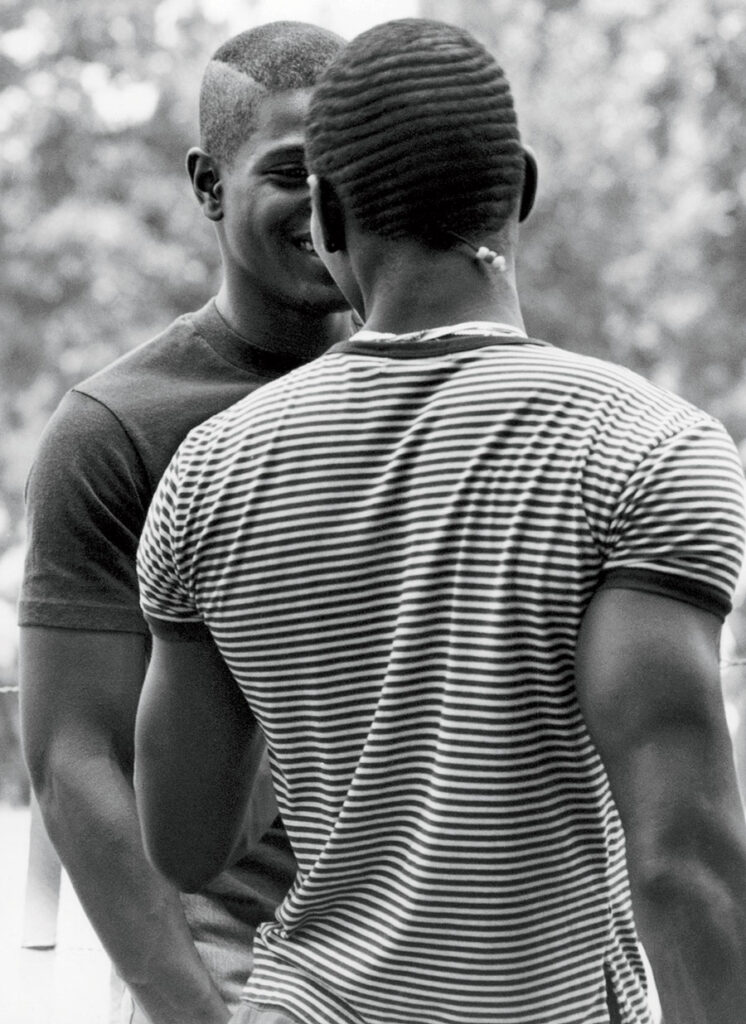

Two Young Men and Waves (1985) by Patric McCoy

Two Young Men and Waves (1985) by Patric McCoy

Some of the exhibition’s most striking work is the photography, which bolsters the time-capsule feel. That includes the work of Patric McCoy, a retired EPA scientist who became a shutterbug in the 1980s, carrying his 35 mm camera whenever he left his South Shore home. He found a group of men eager to peacock for his lens at the Rialto Tap, a long-defunct South Loop pub and sanctuary for queer Black Chicagoans. “I loved that place. It was a dive bar, but it was Cheers too,” McCoy recalls.

The exhibition features five of his shots. As McCoy notes, “It’s a photodocumentation of a phenomenon that existed but was lost. Subsequent generations don’t have the knowledge of what it was like. They think Boystown is the greatest thing since sliced bread.”

Marginal Waters #9 (1985) by Doug Ischar

Marginal Waters #9 (1985) by Doug Ischar

In that same era, Doug Ischar was photographing North Side gays at the Belmont Rocks, a stone-and-grass stretch of the lakefront where they gathered to socialize, sunbathe, and cruise. Four of those images from Berger’s collection landed in the exhibition. “It’s a really beautiful view of how the community had a safe and free place along the lake,” says Berger. “But that space no longer exists.” In 2003, the city replaced the uneven limestone slabs with a concrete retaining wall, removing a piece of the community in the process. “There was a lot of graffiti created by queers on the stones. Those were historical reference points.”

Given the tumultuous times represented in the exhibition, some degree of elegy is unavoidable. But City in a Garden is also a celebration, a call to action, and a hopeful prayer for the future. “To a certain extent, the show frames Chicago as a metropolitan sanctuary for queer people,” says Schneider. Hence the title of its final section: “I’m not arguing Chicago is a utopia, but you can get an idea of what this speculative city in a garden might look like — an idea of what Chicago could become.”