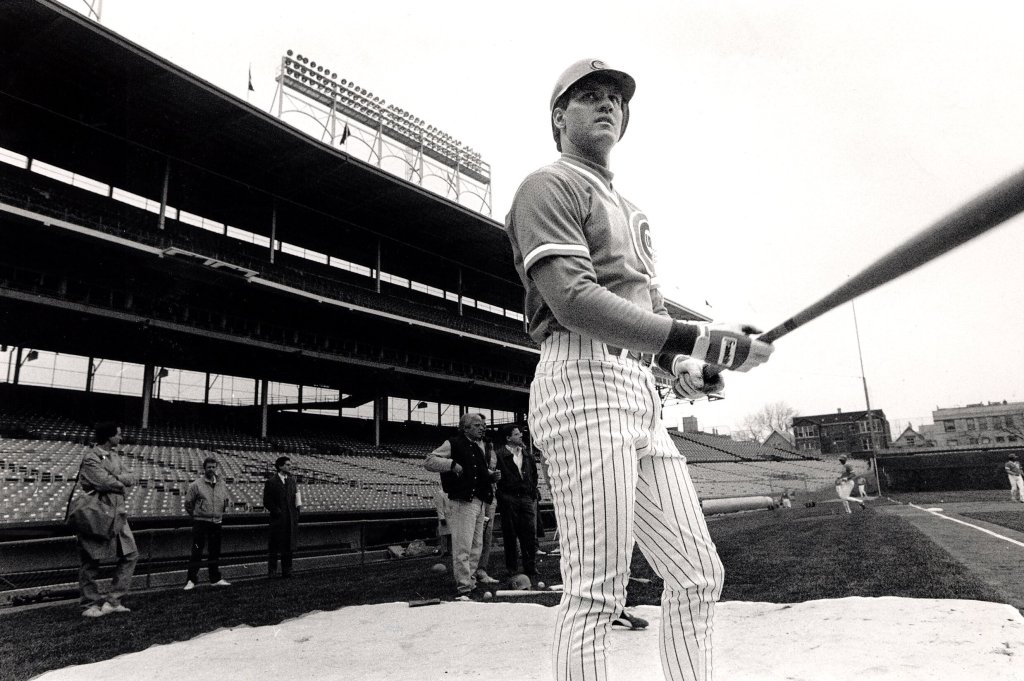

“Big career ahead.”

That’s how longtime Tribune reporter Jerome Holtzman described a recently acquired Chicago Cub Ryne Sandberg in April 1982.

“Outstanding all-around athlete, with excellent instincts in all departments,” Holtzman wrote about the then-third basemen who was named for New York Yankees pitcher Ryne Duren. “Good base-stealer and baserunner. Beneath seemingly calm exterior beats the heart of a tiger, or so it seems.”

“Ryno,” as he was dubbed by Cubs broadcaster Harry Caray, rebounded from an 0-for-31 start with the franchise to earn nine Gold Glove awards, 10 All-Star Games, seven Silver Slugger awards and the 1984 National League MVP.

“But the real legacy of Sandberg’s career is reflected in the respect a laughable organization suddenly earned when he morphed into ‘The Natural,’ a real-life version of Robert Redford’s movie character,” Tribune columnist Paul Sullivan wrote earlier this week about the June 23, 1984, event known as “The Sandberg Game.” “Sandberg helped usher in an era in which the Cubs were no longer a team that could be ignored and showed the world how magical a ballpark could be when everything worked.”

Sandberg died Monday at 65, surrounded by family at his home in Illinois. He battled metastatic prostate cancer and shared news of his remission in August, but four months later he provided an update that the cancer had returned and spread to other organs.

No. 23’s legacy, according to Sullivan, is that he made it cool to go to Wrigley Field again: “That’s just what legends do.”

Here’s a look at highlights from Sandberg’s 15-year career in Chicago.

Jan. 27, 1982

![Larry Bowa, left, and Chicago Cubs coach Gordy MacKenzie [5] congratulate Ryne Sandberg, whose two-out single in the 13th inning gave the Cubs a 3-2 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers on May 29, 1982. (Dave Nystrom/Chicago Tribune)](https://www.europesays.com/us/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/CTC-L-RYNE-SANDBERG-1982-01.jpg) Larry Bowa, left, and Chicago Cubs coach Gordy MacKenzie (5) congratulate Ryne Sandberg, whose two-out single in the 13th inning gave the Cubs a 3-2 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers on May 29, 1982. (Dave Nystrom/Chicago Tribune)The Cubs traded Ivan DeJesus to Philadelphia for “aging but feisty veteran” Larry Bowa and Sandberg — “an untested minor leaguer” — who had been drafted by the Phillies in the 20th round of the 1978 summer draft of free agents.

Larry Bowa, left, and Chicago Cubs coach Gordy MacKenzie (5) congratulate Ryne Sandberg, whose two-out single in the 13th inning gave the Cubs a 3-2 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers on May 29, 1982. (Dave Nystrom/Chicago Tribune)The Cubs traded Ivan DeJesus to Philadelphia for “aging but feisty veteran” Larry Bowa and Sandberg — “an untested minor leaguer” — who had been drafted by the Phillies in the 20th round of the 1978 summer draft of free agents.

Sandberg spent his first three full seasons in the minors. In 1981, at the Phillies’ top farm club in Oklahoma City, he was the American Association’s All-Star shortstop.

Obviously a promising prospect, Sandberg was a September callup and finished the season with the Phillies. Sandberg appeared in 13 games and recorded just six plate appearances — with his first MLB hit coming on a single at Wrigley Field during the second game of a doubleheader on Sept. 27, 1981. (The Cubs won 14-0.) Aware he needed more experience, the Philadelphia brass recommended Sandberg play winter ball in Venezuela.

Bobby Wine, then a Philadelphia coach, also was dispatched to Venezuela. A former big-league infielder, Wine would manage the club and watch over Sandberg, along with four or five other Phillies farmhands.

“He wasn’t too happy about playing winter ball,” recalled Wine. “He wanted to go home. A lot of guys wanted to go home. He struggled and didn’t play that well.”

When Wine returned to Philadelphia, he was convinced Sandberg wouldn’t be a successful major-league shortstop. Ruben Amaro, the general manager at Venezuela, who also had been a big-league shortstop, agreed.

“That’s when the Phillies decided to move him,” Wine said.

Oct. 3, 1982

Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg gloves Butch Benton’s throw after the Mets Ron Gardenhire steals second in September 1982 at Wrigley Field. (Phil Mascione/Chicago Tribune)

Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg gloves Butch Benton’s throw after the Mets Ron Gardenhire steals second in September 1982 at Wrigley Field. (Phil Mascione/Chicago Tribune)

New Cubs general manager Dallas Green — who was also acquired from the Phillies — made Sandberg the opening-day starter at third base following an excellent spring training. The Tribune called Sandberg, “definitely a rookie-of-the-year candidate.”

Sandberg had four hits and scored his 103rd run — setting a team record for a rookie — in the Cubs’ last game of the season. He placed sixth in rookie-of-the-year voting and concluded the year with a .271 batting average.

June 23, 1984

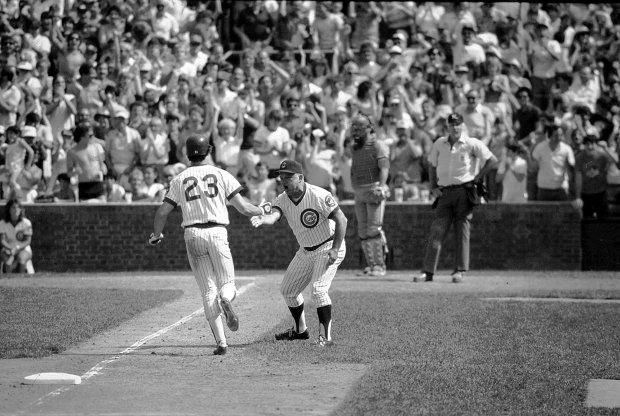

Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg is congratulated by third-base coach Don Zimmer after his ninth-inning home run against the Cardinals tied the score 9-9 on June 23, 1984, at Wrigley Field. (Charles Cherney/Chicago Tribune)

Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg is congratulated by third-base coach Don Zimmer after his ninth-inning home run against the Cardinals tied the score 9-9 on June 23, 1984, at Wrigley Field. (Charles Cherney/Chicago Tribune)

Sandberg hit a pair of late-inning, game-tying home runs off St. Louis Cardinals closer Bruce Sutter in the Cubs’ 12-11, 11-inning win before a crowd of 38,079 at Wrigley Field. It signaled his rise to stardom — setting the second baseman on a course that would earn him the National League Most Valuable Player Award.

The wild, comeback win gave notice to the rest of America that the 1984 Cubs were for real despite a 39-year World Series drought and not a single championship since 1908. That game ignited an unforgettable summer run that ended with a postseason collapse in San Diego, only one game shy of the World Series.

Nov. 13, 1984

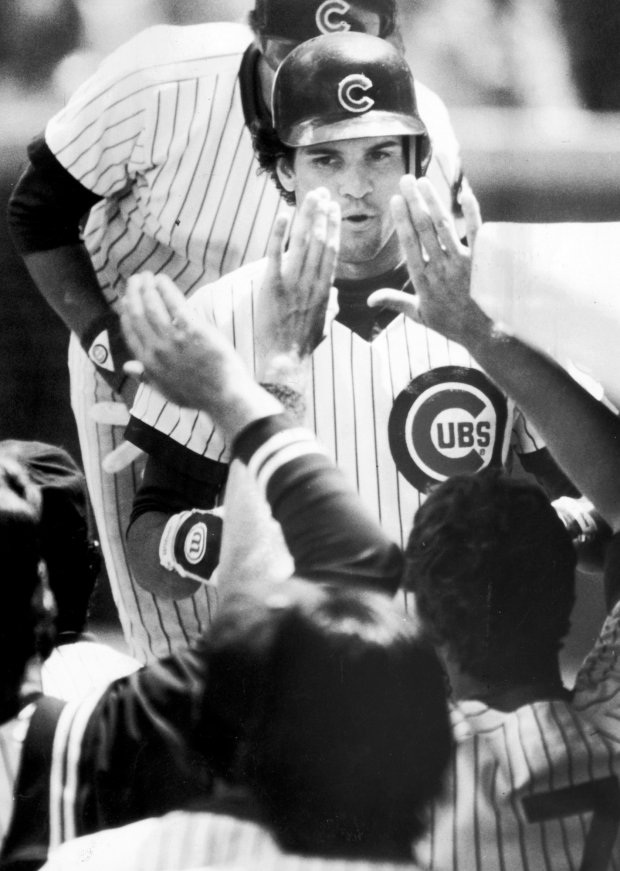

Teammates great Ryne Sandberg after he tripled and scored in the third inning on June 24, 1984. (Jose Moré/Chicago Tribune)

Teammates great Ryne Sandberg after he tripled and scored in the third inning on June 24, 1984. (Jose Moré/Chicago Tribune)

“Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog already had dubbed him ‘the best player I have ever seen’ and ‘Baby Ruth,’ so it seemed almost anticlimactic when Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg was formally anointed the National League’s Most Valuable Player,” Tribune reporter Fred Mitchell wrote. (Mitchell also helped Sandberg write his first autobiography, “Ryno.”)

Sandberg — who hit .314 in 156 games for the fourth-best mark in the league, and got 22 of the 24 first-place votes — was the first Cub since “Mr. Cub” Ernie Banks in 1959 to receive the honor. But Sandberg wasn’t present at Wrigley Field to receive the award — he was at sea as part of a team cruise. He disembarked at Guadalupe to speak to the press via a ship-to-shore phone hookup that cost the Cubs $104 for 20 minutes.

Two weeks later, Sandberg also received his second of nine consecutive Golden Glove awards at second base.

1985

The Cubs’ Ryne Sandberg, stealing second base, protects his head from a wild throw by San Diego catcher Bruce Bochy as second baseman Garry Templeton awaits the throw on July 9, 1985. (Ed Wagner Jr./Chicago Tribune)

The Cubs’ Ryne Sandberg, stealing second base, protects his head from a wild throw by San Diego catcher Bruce Bochy as second baseman Garry Templeton awaits the throw on July 9, 1985. (Ed Wagner Jr./Chicago Tribune)

Stolen bases — 54 — his career best.

July 9-10, 1990

Ryne Sandberg acknowledges the cheers after his three home runs lifted the NL over the AL at the All-Star Game home run competition on July 9, 1990. (Bob Langer/Chicago Tribune)

Ryne Sandberg acknowledges the cheers after his three home runs lifted the NL over the AL at the All-Star Game home run competition on July 9, 1990. (Bob Langer/Chicago Tribune)

After he received 2.26 million votes (second overall to Jose Canseco) and earned National League Player of the Month honors for June, Sandberg hit three home runs to help the National League beat the American League 4-1 in the home run contest.

The next day, Sandberg and fellow Cubs Andre Dawson and Shawon Dunston went 0-for-7 at the plate as the American League shut out the National League 2-0 on a windy, rainy night.

June 13, 1994

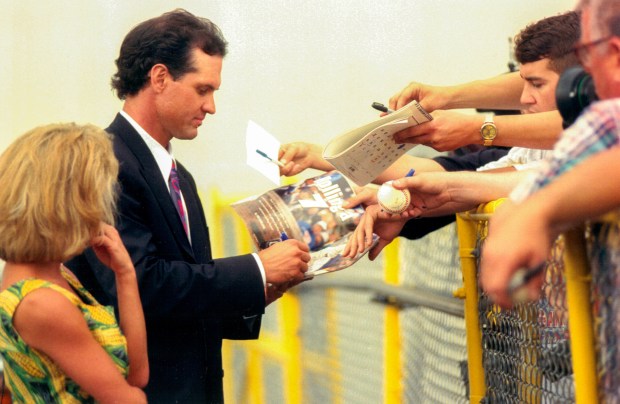

Ryne Sandberg, with wife Cindy, signs autographs outside Wrigley Field on June 13, 1994, after he announced his retirement from baseball. (Nancy Stone/Chicago Tribune)

Ryne Sandberg, with wife Cindy, signs autographs outside Wrigley Field on June 13, 1994, after he announced his retirement from baseball. (Nancy Stone/Chicago Tribune)

Sandberg retired, saying he wanted to devote more time to his family and adding he had “lost the edge it takes” to play.

After resolving matters in his personal life and remarrying, the future Hall of Famer returned to the Cubs after the 1995 season and hit 25 home runs with 92 RBIs in his comeback year.

2005

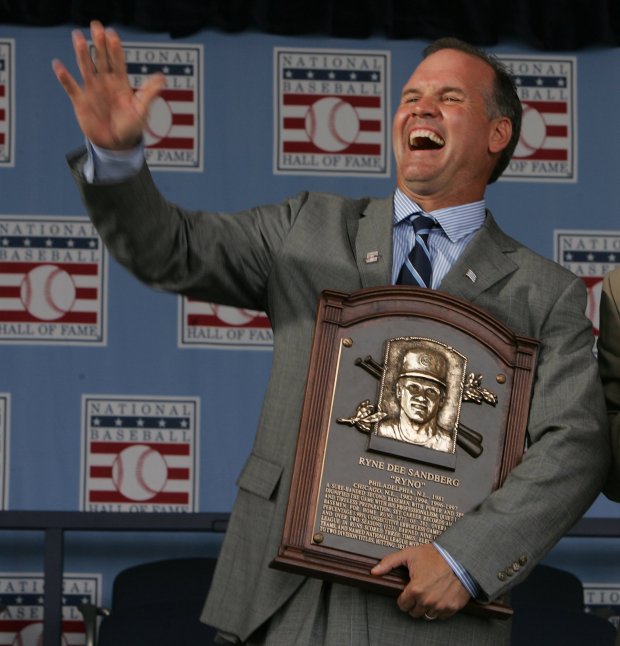

Ryne Sandberg, clutching his Hall of Fame plaque, waves to the Cooperstown, New York, crowd on July 31, 2005. (Phil Velasquez/Chicago Tribune)

Ryne Sandberg, clutching his Hall of Fame plaque, waves to the Cooperstown, New York, crowd on July 31, 2005. (Phil Velasquez/Chicago Tribune)

Sandberg was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He delivered a stirring speech that criticized the products of the steroid era.

“When did it become OK for someone to hit home runs and forget how to play the rest of the game?” he said.

Sandberg spoke about playing the game “right because that’s what you’re supposed to do” and said if his election into the Hall validates anything it’s that “learning how to bunt, hit-and-run and turning two is more important than knowing where to find the little red light (on) the dugout camera.”

Trumpets play as former Chicago Cubs second baseman and Hall of Fame player Ryne Sandberg is introduced as his No. 23 jersey is retired before a game against the Florida Marlins at Wrigley Field on Aug. 28, 2005. (José M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune)

Trumpets play as former Chicago Cubs second baseman and Hall of Fame player Ryne Sandberg is introduced as his No. 23 jersey is retired before a game against the Florida Marlins at Wrigley Field on Aug. 28, 2005. (José M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune)

Sandberg mentioned nine of his former Cubs teammates during his speech. Sammy Sosa, who was on the rise in Sandberg’s final season in 1997, wasn’t among them.

“You hit a home run, you drop the bat, put your head down and run around the bases because the name on the front of your uniform is a lot more important than the name on the back,” Sandberg said. “That’s respect.”

He also had his No. 23 retired by the Cubs on Aug. 28, 2005, at Wrigley Field.

Jan. 22, 2024

Ryne Sandberg, center, throws out a ceremonial first pitch with former Chicago Cubs Billy Williams, Lee Smith, Fergie Jenkins and Andre Dawson on April 1, 2024, in the home opener at Wrigley Field. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Ryne Sandberg, center, throws out a ceremonial first pitch with former Chicago Cubs Billy Williams, Lee Smith, Fergie Jenkins and Andre Dawson on April 1, 2024, in the home opener at Wrigley Field. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Sandberg disclosed his diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer. He shared news of his remission that August, but four months later, he provided an update that the cancer had returned and spread to other organs, prompting more intensive treatment.

“The support has been tremendously overwhelming right from the first week, and it’s continued throughout,” he told the Tribune in June 2024. “It’s just been incredible and I think that’s been as much medicine to me as anything really.”

June 23, 2024

Former Cubs player Ryne Sandberg attends a dedication ceremony for his statue outside Wrigley Field on June 23, 2024. (Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune)

Former Cubs player Ryne Sandberg attends a dedication ceremony for his statue outside Wrigley Field on June 23, 2024. (Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune)

Sandberg’s 11 grandchildren pushed a button together that unveiled a statue of his likeness outside Wrigley Field — 40 years after the “Sandberg Game.”

“Some of the things I wanted on the statue was being on the balls of the feet, being ready for every single pitch,” Sandberg told reporters after the statue dedication ceremony at Gallagher Way. “My defense was very important for me. I thought, for me, it was ‘Bring your glove every single day.’ You might go into some hitting slumps, but as far as defense goes, as long as I did my pregame work I wanted to play defense every day for the pitcher, for everybody on the field.”

“I’ll never forget that day and what that all means,” Sandberg told the Tribune in February. “It’s incredible to see. And oftentimes I see a few fans around there posing for pictures. On occasion, I’ve walked up to them and said, ‘This is pretty cool, isn’t it?’”

Want more vintage Chicago?

Thanks for reading!

Subscribe to the free Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter, join our Chicagoland history Facebook group, stay current with Today in Chicago History and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Kori Rumore at krumore@chicagotribune.com.