Study context

The management of genetic testing results and consequent risk information is not explicitly addressed in Swedish national legislation [4]. However, as noted in the preparatory works to the Genetic Integrity Act (2006:351), HCPs may disclose genetic test results to ARRs with proband consent, with consideration of individual circumstances.

Specialised healthcare investigating hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes is offered at cancer genetics clinics at Sweden’s university hospitals. All clinics were invited, and four met criteria for participation (see study protocol [20] for details). One clinic had poor adherence to the study protocol, failed progression criteria and poor quality at audit. This site was closed after a year, and probands from this site were not included in any of the results.

Trial design and participants

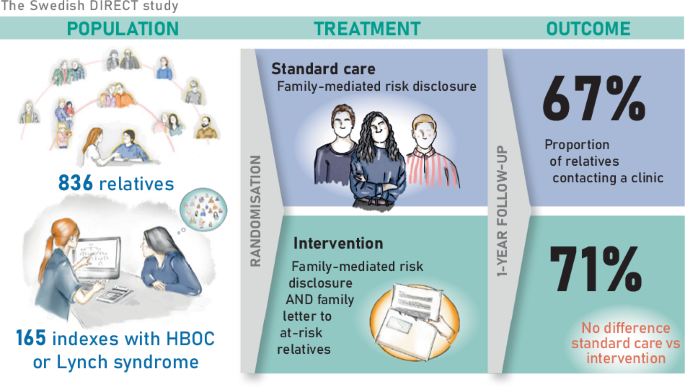

The DIRECT study was a pragmatic, open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NTC04197856, with protocol previously published [20]. Patients over 18 years at cancer genetics clinics were pre-screened and invited to participate if they were eligible for genetic screening or predictive testing for suspected HBOC (the genes BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2) or Lynch syndrome (the genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2).

The inclusion criteria were (a) signed informed consent, (b) a PV in a gene associated with HBOC or Lynch syndrome, or a negative genetic screening but belonging to a family fulfilling clinical criteria for familial breast cancer or familial colorectal cancer and (c) having at least one eligible ARR, i.e. a family member with no previous contact with a cancer genetics clinic who was deemed to be recommended GC within a year. Inclusion and randomisation were done after the test results were known, but before post-test counselling. The included participants were both cancer patients who underwent genetic screening and individuals who underwent predictive testing, collectively referred to as ‘probands’ onwards. The probands were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by study site, gender, age group and family diagnosis. In this article, we report the outcomes in HBOC and Lynch syndrome families. The outcomes of the full cohort are available at our data repository.

Standard care

All probands received standard care according to current local clinical practice, which included post-test GC with an HCP who also encouraged family-mediated risk disclosure to ARRs. Standard care included written information produced by the different sites, and the content was largely similar across sites and over time. The printed information included details on hereditary cancer, cascade testing, risk management and contact information for cancer genetics clinics.

Definition and identification of eligible ARRs

At the post-test counselling session, the proband, together with the involved HCPs, identified eligible ARRs >18 years at the end of follow-up, with no previous contact with a Swedish cancer genetics clinic. The relatives who were eligible as ‘at-risk’ were adult male and female relatives who, according to the involved HCP, could be offered cascade GC and testing for the familial PV within 12 months. In general, the living ARRs with the closest (genetic) relationship to the proband were considered eligible and offered cascade GC and testing before subsequent relatives were eligible. However, more distant (non-first-degree) ARRs were considered eligible if the first-degree relative was deceased or, due to other reasons, was unavailable for cascade GC and testing. During our weekly study meetings, the involved HCP consulted the study team if they were unsure about how to define eligible ARRs, but the final decision on who to list as an eligible ARR and thus to be recommended GC within a year was up to the local HCP. Contact details of ARRs in both control and intervention groups were retrieved in collaboration between the proband and the HCP. At times, the HCP and the proband collaboratively employed official publicly available sources to identify ARRs’ contact details.

Intervention

Probands in the intervention group, as well as the control group, received standard care and both arms did the listing of eligible ARRs as outlined above. In addition, the intervention group was offered the service of the HCP sending a direct letter to their eligible ARRs. The proband approved or denied contact with each eligible ARR. The direct letter included information about the specific familial investigation and the possible implications for them and their family. Templates of direct letters are published in the protocol [20].

The letters were sent ~1 month after the proband had received post-test GC. In some cases, the timing was adjusted according to the proband’s preference. If a listed ARR had already contacted the cancer genetics clinic before the distribution of letters, a letter was not sent to that specific ARR. Distribution of letters was paused before national holidays to reduce the possibility of delayed contact with an available HCP. The letters were sent via registered mail, requiring proof of identity for the recipients to retrieve the letters. The cancer genetics clinic received the letter in return, should the addressee fail to collect it within 2 weeks.

Outcomes: uptake of genetic counselling in eligible at-risk relatives

In this study, we used ARRs’ contact with a cancer genetics clinic as a proxy for the uptake of GC. The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible ARRs contacting a Swedish cancer genetics clinic within 12 months after the proband received post-test counselling. This follow-up period was chosen because we believe that, from a clinical perspective, the eligible ARRs should preferably have received GC within this period of time. The outcome ‘contact’ was defined as the ARR having an interaction with a Swedish cancer genetics clinic (by phone, video, electronic communication, or a physical meeting) that was documented in the ARR’s patient record or the family pedigree during the follow-up period. Outcome data were collected by the study coordinator at each site, by checking local patient data registries and/or asking the other national collaborating units if they had any registered contact with the ARR within 12 months after inclusion of the proband. Thus, all Swedish cancer genetics clinics were involved in providing data for the primary outcome. Only a few ARRs declined GC after contacting the clinics at the participating study sites (HE, AÖ, AR, personal communication).

The following study-related information on ARRs was reported at the family level: total number of eligible ARRs who had a documented contact with any Swedish cancer genetics clinic within 12 months, and total number of eligible ARRs at the time of inclusion. ARRs’ gender (female and male) and degree of kinship (first-degree and more distant) were detailed. The total number of ARRs, including those who initially lacked contact details, was also reported. Difference in uptake was evaluated both for eligible ARRs (for which contact details were available, main analysis) and for all ARRs (eligible ARRs and ARRs to whom the proband lacked contact details).

Psychosocial outcomes

Questionnaires were administered to the probands at two time points, baseline at inclusion and ~6 months later. Questionnaires used validated instruments measuring generic health-related quality of life (RAND-36) [21], anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, STAI) [22] and cancer worry (CWS) [23]. Non-respondents received one reminder per questionnaire. In this paper, we compared the emotional well-being component of RAND-36, the STAI-S and the 8-item CWS between intervention and control, both at baseline and 6 months follow-up.

Statistical methods

To detect a 12.5% difference in uptake of GC between groups, we estimated a need to recruit outcome data for 490 ARRs. Main outcome measures were evaluated using chi2-tests and logistic regression. As grouping effects at the family level may affect outcomes, we expanded the logistic model to a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) with a logit link. Multivariable GLMMs were adjusted for the stratification variables (gender and age group of the proband, family diagnosis and study site) as well as degree of kinship and gender of the ARRs. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for non-normality. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for comparison of family size and the psychosocial measurements. P values 24].