After the 1994 Northridge earthquake, parks across the San Fernando Valley filled with families left homeless by the destruction or simply too afraid that an aftershock might pancake their home.

An estimated 14,000-20,000 people lived in those tent cities, and many were Latino immigrants who had nowhere else to go.

Newsletter

You’re reading the Essential California newsletter

Sign up to start every day with California’s most important stories.

Enter email address

Sign Me Up

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Noel Mendoza, a migrant from Nicaragua who spent two weeks camping at one park because she didn’t feel safe in her crack-filled Canoga Park apartment, told The Times back then: “I was a refugee there and now I’m a refugee here.”

It’s one thing to seek safety in public spaces, as one tent city dweller said, to have nothing between oneself and the stars.

But what if being out in public is the thing that places you at risk?

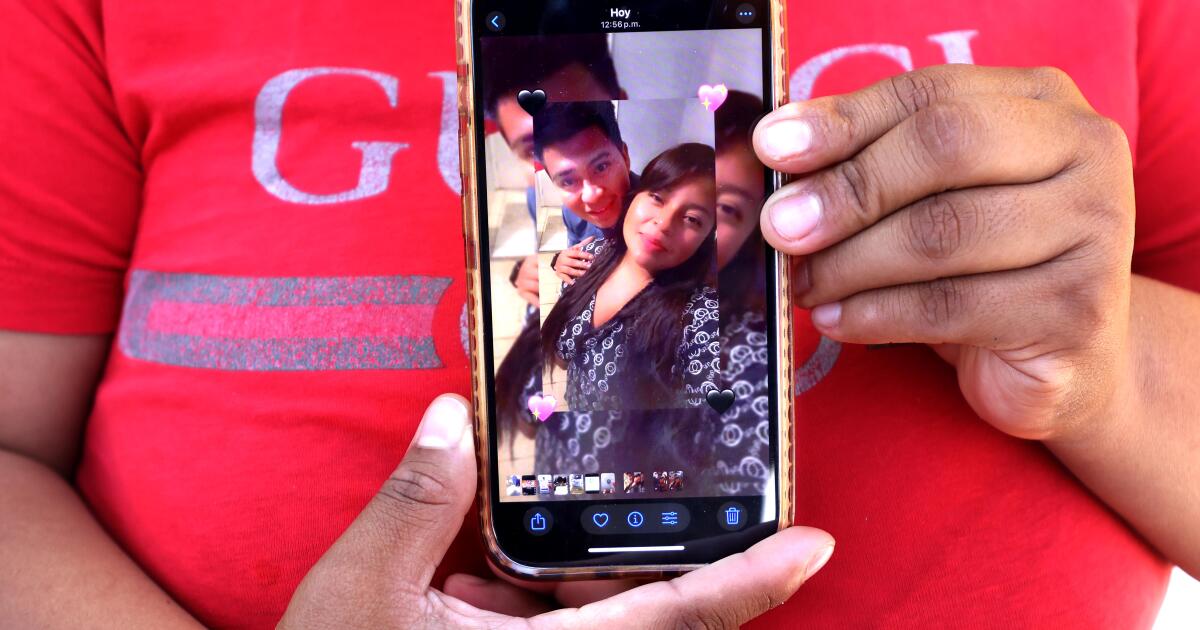

This forgotten piece of seismic history came to mind as I listened this week to experts talking about how L.A.’s summer of ICE has brought waves of emotional struggles to immigrant families. There are so many facets to the raids — the legal issues, questionable tactics, protests, economic impacts, political fallout — that the emotional fallout easily gets lost.

Juadulupe Flores and her four-year-old daughter Yijan share breakfast at a park in the San Fernando Valley after 1994 quake

(TIMOTHY CLARY/AFP via Getty Images)

Immigration raids take a complex toll

We are now nearly two months into President Trump’s immigration crackdown, which has led to more than 3,000 arrests in Southern California alone. The raids have upended countless lives.

But we’ve reached that inevitable moment in the story when some begin to turn away. What shocked in June seems like just part of the new normal in August. It’s summer. Vacations. Jeffrey Epstein, the tsunami that wasn’t.

Parts of Los Angeles are moving on, as we do no matter the calamity. But for those in the middle of the story, there is no escape. Just ask someone who lost their home in January. Or someone who lost a job, who had to go underground or whose loved one was deported after a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid.

I attended a forum this week on mental health and the raids put together by Boyle Heights Beat, the community news site that has been aggressively covering the ICE operations with news and resource guides. Experts offered a sober window into how the raids have impacted the mental health, individually and collectively, of immigrants and their communities. Some quotes that stayed with me:

- “I see a white van and my body automatically freezes.”

- “You become a caregiver.”

- “You have survivor’s guilt.”

- “Children step up more to help their parents, and they internalize their parents’ fears.”

The forum particularly illuminated secondary traumas, such as the burden on children who are here legally helping their parents; the new, sudden role of caregiver for people who must now look out for others whose lives are on hold; and the increased irritability, drinking and guilt that come with all this stress.

The message of the experts was clear: These times require strong coping skills and a keen sense of your own limits, even if that sometimes means turning off the news and finding moments of joy amid the uncertainty.

The public might move on, but the story doesn’t end

In the days after the Northridge quake, the tent cities became a source of fascination to me and so many others trying to make sense of what had just happened. I remember being deeply moved at the way large extended families set up little cul-de-sacs under the trees of a neighborhood park, taking comfort in having all their loved ones safely in one place as the earth beneath them rumbled. As someone who cowered alone each night in my tiny apartment, wondering whether that vibration was a new quake or my upstairs neighbor rewatching “Star Wars” on his VCR, their peace brought me comfort.

The camp became one symbol for some political activists who charged officials were not paying enough attention to quake victims in poorer, Latino communities. There were protests and news stories, and more aid flowed to the east Valley.

Eventually even the great quake receded from the news. The aftershocks lessened. The broken freeways were repaired. The tents disappeared. Life moved on.

The end remains elusive for those dealing with the ICE sweeps. And this uncertainty is why the experts urged people to pace themselves and accept what they can and cannot do.

As one said, “If you can’t take care of yourself, you can’t take care of other people.”

The week’s biggest stories California PoliticsClimate and WildfiresHigher educationHousing and HomelessnessOther big storiesMust readsOther meaty readsFor your weekend

(Michael Owen Baker / For The Times)

Going outStaying inL.A. Timeless

A selection of the very best reads from The Times’ 143-year archive.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Jim Rainey, staff writer

Diamy Wang, homepage intern

Izzy Nunes, audience intern

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Andrew Campa, Sunday writer

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com. Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.