A new report from the New York City Public Advocate paints a stark picture of how limited-English proficient (LEP) New Yorkers are systematically denied access to critical public services from healthcare and housing to education and emergency response.

The 64-page report, titled “Let’s Talk: A Review of Language Access in NYC,” released last week, highlights deep gaps in how city agencies provide services to non-English speakers, despite city laws requiring them to do so.

Five months ago, the Trump administration signed an executive order declaring English the official language of the United States, thus rescinding federal obligations to serve LEP populations, and revoking a Bill Clinton executive order established in 2000 which aimed to improve access to services for LEPs.

Immigration News, Curated

Sign up to get our curation of news, insights on

big stories, job announcements, and events happening in immigration.

Please check your email for further

instructions.

The new order eliminates federal obligations to translate documents or offer interpretation in languages other than English. Immigrant advocates say this decision will limit access to critical public services for millions of non-English speakers.

New York Public Advocate Jumaane Williams describes the order as “part of a broader plan to deny the existence of identities and particularly Black and Brown immigrants and create fear and harm.”

To help address language access issues in New York, the report calls for deep reforms to city policies and infrastructure, including the creation of a centralized Office of Language Access, expanded funding for interpreter cooperatives, and a citywide bilingual pay initiative. (Full recommendations are listed below.)

“Focusing on language access has always been important,” Williams said to Documented. “It’s important even more now, based on what’s happening on a federal level and all the fear that’s going through these communities.”

“Language access bridges resource disparities, opens doors to opportunity, and ensures everyone’s voice is heard,” the report states. “In some cases, it can be the difference between life and death.”

During Hurricane Ida in 2021, 13 New Yorkers, many of them Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency, died in flooding. A lack of timely, multilingual emergency alerts may have played a role, according to the New York State Attorney General’s Office. At the time, federal alerts were issued only in English and Spanish.

Also Read: Why It’s So Hard for Latinos to Keep Spanish Alive in the U.S.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, city agencies often distributed essential public health information exclusively in English. City Meals on Wheels, for instance, reported receiving vaccination fliers only in English despite requesting materials in multiple languages.

In schools, LEP parents struggled to assist children in navigating remote learning platforms. The Department of Education lacked sufficient bilingual staff and failed to provide adequate translated materials, contributing to a learning gap for English Language Learners.

Patchwork implementation

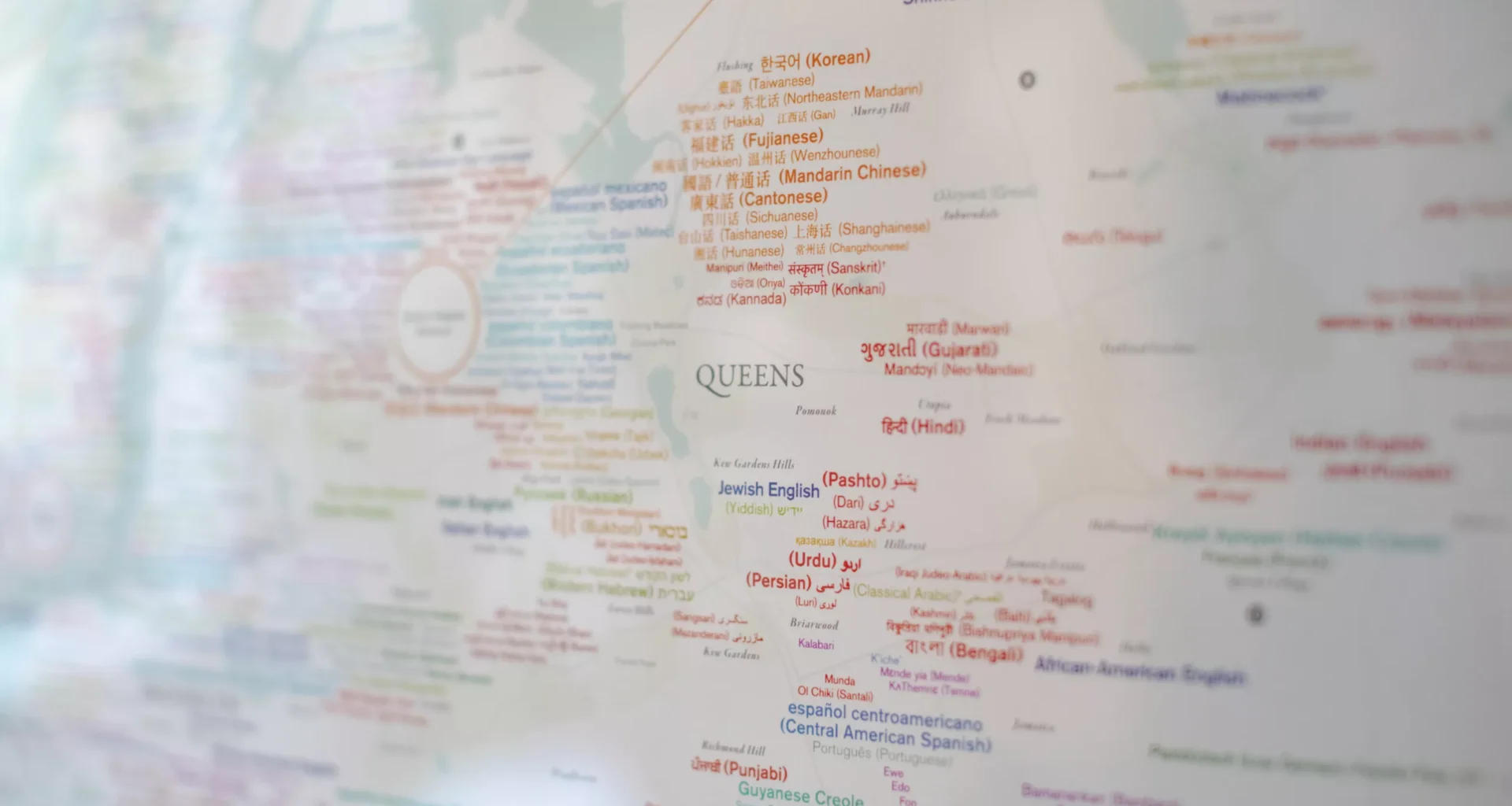

Nearly two million city residents have limited English proficiency, according to the report. Despite this need, the report finds that most agencies rely heavily on third-party language vendors. LanguageLine Solutions held $91.9 million in city contracts during fiscal years 2023 and 2024. Accurate Communication and Geneva Worldwide followed closely with tens of millions more.

Additionally, the report notes other systemic gaps. A city-run secret shopper program designed to evaluate whether agencies follow Local law 30 by providing interpretation services and translated materials. Staffed primarily by multilingual students, the program lacks formal enforcement power and offers only a partial picture of service quality. The consequences of these gaps are felt most acutely in emergencies.

“Just because you’re spending a lot of money doesn’t mean you’re doing right or efficiently,” Williams said. A lot of times, that money is going to third party organizations that aren’t even from the city. That money should stay in the city.”

A growing population, a shrinking response

Recent waves of asylum seekers and immigrants have also strained the system. The city has seen more than 200,000 new arrivals over the past three years. Many are speakers of languages not covered by the city’s top ten languages, including Wolof, Haitian Creole, and various Indigenous dialects such as K’iche’ and Garifuna.

In the shelter system, LEP residents reported difficulty accessing services and mental health care. In several tragic cases, the lack of communication reportedly contributed to suicides among migrants housed in city facilities.

Testimony from a joint City Council hearing in April confirmed these experiences. In response, the Council allocated funding for new initiatives, including the Community Interpreter Bank and the Afrilingual worker cooperative, a multilingual, worker-owned organization providing services in underrepresented African languages.

“You want to make sure that there’s cultural competency,” Williams said. “When you have things like a worker cooperative that is localized in the community, that has a good powerful competency, then doing translation, you know it’s happening in the best way particularly for languages that are not as popular.”

The Public Advocate told Documented that his office will push for the report’s recommendations to be enacted through both policy and legislation. His team is working with the City Council to draft new laws and secure additional funding.

“We’re going to be looking to see if we can get that passed through the City Council,” he said. “It’s also important to remember how critical this is not just for people seeking help, but for everyday New Yorkers trying to get through school, understand an alert, or just live their lives.”

The report outlines five major recommendations for systemic reform that include the creation of a new office, a bilingual pay program, and more worker-owned language cooperatives.