The overall incidence of GSDs is approximately 1 case per 20,000–43,000 live births, and 80% of hepatic GSDs are caused by types I, III, and IX [14]. The main clinical findings of GSDs are hypoglycemia, hepatomegaly, and short stature. It is very difficult to clinically differentiate between the subtypes. The definitive diagnosis and subtype differentiation in patients suspected of having GSD is made through molecular analysis. In addition to severe forms, patients may also present with mild clinical findings. Long-term complications include hepatic lesions such as hepatic adenoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, splenomegaly, renal involvement findings such as chronic kidney disease, chronic kidney failure, urolithiasis, and nephrocalcinosis, hypertension, neurological involvement findings such as cognitive delay, epilepsy, and neuropathy, cardiac findings including cardiomyopathy, QT prolongation, and pulmonary hypertension, findings secondary to cirrhosis including portal hypertension, ascites, and esophageal varices, polycystic ovary syndrome, delayed puberty, osteopenia/osteoporosis, gout, pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, and myeloid malignancy [14].

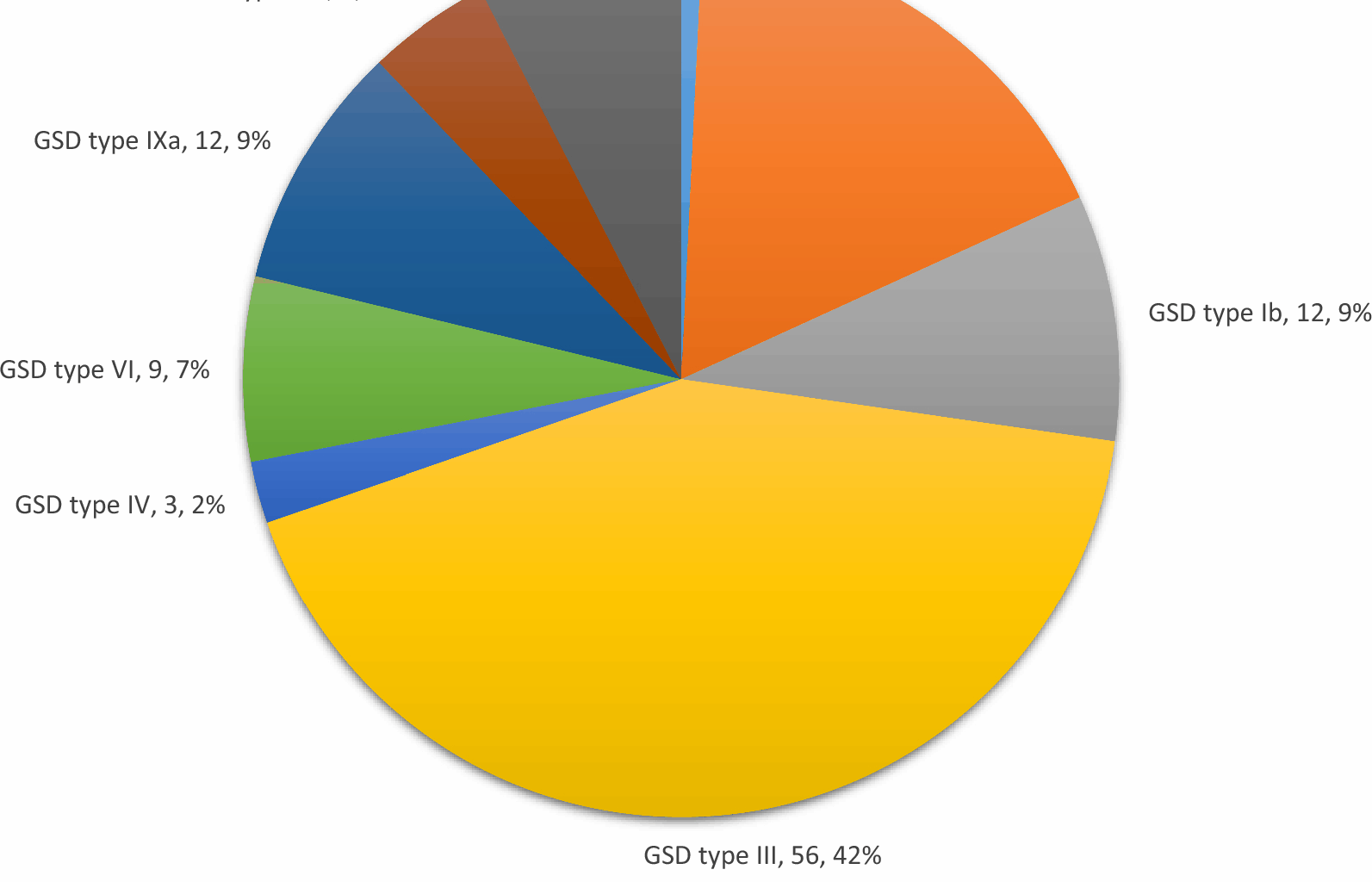

According to the literature, studies conducted in different regions report that the most commonly observed types are Ia, III, and IXa [2, 15,16,17]. A study conducted in Turkey involving 38 patients with hepatic GSD reported that the most common type was GSD type III at a rate of 39.5%, followed by type Ia at 31.5% [18]. In the present study, the most common type was GSD type III at 42.4%, followed by type Ia at 17.4% and types IXa and Ib at 9.1%. Additionally, the frequently observed types in the literature, namely types I, III, and IX, constituted 90.2% of the patients in our study. However, the reason for the most commonly observed type not being the same in different studies may be attributed to variations in patient numbers and genotypic differences. In a study evaluating the subgroups of GSD type I, the Ib/Ia ratio was found to be 24% [10]. In a study evaluating GSD type I patients from Turkey, this ratio was found to be 11.1% [19]. In the present study, the Ib/Ia ratio was 52%, and a larger number of patients were diagnosed with Ib. This situation may be attributed to the high frequency of consanguineous marriages and high birth rates in our region. The most common presenting complaints in our patients were abdominal distension, hepatomegaly detected during hospital visits for other reasons, abnormal liver function tests, hypoglycemia, family screening, and growth retardation. Patients with GSD type Ia–b most commonly presented with hypoglycemia, while those with type IXc presented with hepatomegaly, and patients with types III and IXa presented with abdominal distension. Based on the findings of the patients, it can be stated that the presence of abdominal distension upon presentation or the detection of hepatomegaly and/or abnormal liver function tests during hospital visits can serve as an indicative finding for GSD. In a multicenter study involving 231 patients with GSD type Ia, the average age at presentation was reported to be 6 months (ranging from 1 day to 12 years), with 80% of patients presenting before age 1. The most common reasons for presentation were abdominal enlargement in 83% of cases and acute metabolic decompensation in 71% [10]. It was reported that the average age at presentation for patients with GSD type Ib was 4 months (ranging from 1 day to 4 years), with 90% of patients presenting with symptoms before age 1 [10]. In a study conducted in China on patients with hepatic GSDs, the main complaints were reported as abdominal distension or hepatomegaly (20/49), abdominal distension and elevated liver transaminase levels (16/49), hepatosplenomegaly (3/49), abnormal liver function detected during hospital visits for other reasons (6/49), and growth retardation (1/49). It was reported that 91.67% (22/24) of GSD Ia patients had abdominal distension with hepatomegaly. In the same study, the age at diagnosis was reported to be 4.84 ± 3.16 years for type Ia, 2.22 ± 0.86 years for type IIIa, and 2.61 ± 1.19 years for type IXa [20]. In a study examining GSD type VI patients, the median age at diagnosis for 63 cases was found to be 5.3 years [21]. Although the ages at diagnosis vary across different series, in the present study, the earliest diagnosed types were types Ia, Ib, and IXc. Although the mean age at diagnosis was 14.09 ± 18.7 (1–82) months for type Ia patients, the median age at diagnosis was 6 months. Furthermore, since the mean age at diagnosis seemed to be high, the median age at diagnosis was similar to that reported in most studies, and patients received a diagnosis on average within 3 months after their first presentation. While there are some similarities between our results and the data in the literature, the differences are most likely due to environmental factors and genetic differences. The early diagnosis ages of our patients with types Ia and Ib may be attributed to the more pronounced hypoglycemia in this group, which tends to manifest earlier as a clinical symptom.

Interestingly, 6.1% of our patients were twins. According to 2023 data from Turkey, the national rate of multiple births is 3.3%, suggesting a higher-than-expected frequency of twinning in our cohort [22]. Two families with type Ib and one family with type IXc had twin children, and there was also one patient, each with types Ia and III, who had a healthy twin. In other words, 5 out of the 35 patients with types Ia and Ib were twins (14.3%). In the existing literature, a study evaluating 29 patients with GSD type Ia and 7 patients with type Ib reported that 4 of the type Ia patients were 2 twin siblings, and other studies reported Korean twins with GSD Ia and Polish twins with type IIIb [23,24,25]. The high number of twins in our patient group was a remarkable finding.

In the study conducted by Jorge et al. on 11 patients with GSD type I, it was reported that 8 patients (72.7%) had a normal BMI for their age, while 3 were classified as overweight. When examining height, it was observed that 4 patients (36.4%) were classified as short for their age [26]. Hijazi et al. reported that 40% of patients with GSD type III had a normal BMI, 20% were overweight, and 40% were obese, and the mean BMI of the patients was found to be 28.6 ± 7.4 [27]. In a study that performed phenotyping of GSD type IX, it was reported that growth retardation was observed in 58.3% of patients with GSD type IXa, 87.5% of patients with GSD type IXb, and 70.8% of patients with GSD type IXc [28]. In the present study, when examining the weight SD score (SDS) of the patients at the time of diagnosis, it was found that 19 patients (14.4%) had a body weight of

Due to the prominence of short stature over body weight, when evaluating the BMI SDS in these patients, it was found that only 3 patients had a BMI of + 2 SDS (2 with type Ia, 2 with type Ib, 8 with type III, 1 with type VI, 1 with type IXa, 2 with type IXb, and 2 with type IXc), and 111 patients had normal values. These results emphasize the necessity of using BMI SDS to evaluate the nutritional status of patients with short stature.

In a study conducted on hepatic GSD, 18% of patients were found to have height 29]. When 113 patients with anthropometric measurements during follow-up were evaluated, it was found that 46 patients (%40.7) had short stature, 15 patients (%13.3) had body weight 30]. As a guideline, in GSD type I, the serum concentrations of AST and ALT increase and often return to normal or near-normal levels with appropriate treatment. In contrast, AST and ALT levels are typically higher in GSD types III, VI, and IX, and increased levels tend to persist despite treatment [31]. In a study involving 21 patients diagnosed with GSD type III, the median values of ALT and AST were found to be above the laboratory reference values. However, while these values were higher in patients who progressed to cirrhosis, no statistical difference was detected [27]. In a study examining patients with GSD type VI, elevated AST/ALT levels were observed in 93% of the patients, and it was noted that TG levels were mildly elevated in these patients [32]. In a study evaluating the subtypes of GSD type IX, it was reported that patients with GSD type IXc had higher levels of AST/ALT and hypertriglyceridemia compared to patients with GSD types IXa and IXb [28]. In a study conducted by Lu et al. on children diagnosed with GSD type VI in China, it was reported that transaminase elevation occurred in 10 patients (91%), while hyperlipidemia was observed in 3 patients (27%) [33]. In the present study, the mean ALT and AST levels were above the reference values for all GSD types. Mean AST and ALT levels were highest in GSD types III and IXc and lowest in types 0, IXb, and Ib. In our patients, AST and ALT levels tended to remain high despite treatment in GSD types III, IV, and IXc. The reason for this may be the more permanent liver damage observed in types IV and IXc, while in type III, muscle involvement could be a contributing factor. When we looked at our patients, 95.5% had elevated AST and 84.8% had elevated ALT levels at the time of diagnosis, reinforcing the conclusion that elevated levels of these tests are a significant indicator of GSD. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that in 50% of type Ib and type IXb patients, ALT levels are normal even when AST levels are elevated, which can be a significant clue for diagnosing these types. Additionally, the normalization of AST and ALT levels during follow-up, especially in type Ib and type IXb patients, is an important finding.

In a retrospective multicenter study, it was reported that hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia were more prevalent and severe in patients with GSD type Ia compared to patients with GSD type Ib. Hypercholesterolemia was reported in 53.4% of patients with GSD type Ia and 14% of patients with GSD type Ib, while these rates were 91.3% and 78.6% for hypertriglyceridemia, respectively. The same study reported that 57% of the patients had uric acid levels high enough to require xanthine oxidase (XO) inhibitors. Among the patients using XO inhibitors, 29% continued to have elevated serum uric acid concentrations despite treatment, and 14% experienced complications related to hyperuricemia [10]. In the present study, TG levels were found to be particularly high in GSD type Ia and type Ib patients compared to other groups. The finding of higher TG levels in GSD type Ia and type Ib patients compared to other groups aligns with other studies in the literature. In our patients, 12.9% had elevated uric acid levels requiring treatment, with nephrolithiasis developing as a complication in four cases. Similarly, when the AST, ALT, and TG levels of the 13 patients who reached adulthood were evaluated before and after, it was observed that the final values decreased compared to the initial values; however, this decrease was not statistically significant, except for the ALT levels. In patients aged > 18 years, the mean ALT values were 232.4 ± 192.6 U/L at the time of diagnosis and 103.1 ± 53.6 U/L at the final follow-up (P

Ultrasonographic imaging plays an important role in the evaluation of hepatic GSDs. In GSD type 0, hepatomegaly is not observed due to the deficiency in glycogen synthesis in the liver. Additionally, ketotic hypoglycemia and postprandial hyperglycemia without hyperlacticacidemia and hyperalaninemia during fasting have been reported in the literature [34]. In our study, ketotic hypoglycemia was detected in the only patient with GSD type 0 who presented due to a seizure. The patient was short in stature. There was no hepatomegaly, and liver enzymes were normal. Consistent with the literature, postprandial hyperglycemia was detected during follow-up. Hepatomegaly can be considered a common feature of GSD types I, III, IV, VI, and IX. In a previous study, ultrasonographic findings of patients with GSD type I, diagnosed through liver biopsy, were examined. Hepatomegaly was detected in 13 patients (93%), and increased liver echogenicity was found in 11 patients (79%) [35]. In a study evaluating patients with GSD types VI and IX, hepatomegaly of varying severity, from mild to marked, was observed in the entire patient population, and increased liver echogenicity was frequently noted [32]. In a study evaluating patients with GSD type VI, hepatomegaly was detected in 61 out of 63 patients (96%), and splenomegaly was found in 3 patients (4.8%) [21]. In a study evaluating patients with GSD type IX, hepatomegaly was reported in 93% of patients with type IXa, 94% with type IXb, and 100% with type IXc [28]. Similar to the present study, a previous study reported hepatomegaly at a rate of 80% in patients with hepatic GSDs [36]. In the present study, hepatomegaly was detected in 124 patients (93.9%), and hepatosplenomegaly was found in 27 patients (20.5%), which was consistent with the literature. Among the patients with hepatosplenomegaly, there were 22 with type III, 2 with type Ib, and 1 each with types IV and IXa–c. The age at diagnosis and the disease duration are also important factors influencing the frequency of hepatomegaly. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment can reduce the development of complications such as hepatomegaly.

In a study evaluating 288 patients with GSD types Ia and Ib, prematurity was reported in 3%, low birth weight in 10%, and congenital heart anomalies in 3% of the cases. Additionally, pancreatitis was reported in three patients and cholelithiasis in two patients [10]. In the literature, a horseshoe kidney was reported in a patient with GSD type Ib [37]. Among the patients included in the present study, the rate of low birth weight was 12.1% (16/132). When examined by type, the rates of low birth weight were as follows: GSD type Ia–b 14.3% (5 out of 35), type III 8.9% (5 out of 56), type VI 22.2% (2 out of 9), type IXb 16.7% (1 out of 6), and type IXc 30% (3 out of 10). The high rate of low birth weight in these patients may be related to the relatively high incidence of twin births observed in our cohort, or to the low availability of actively usable glycogen stores during the intrauterine period. However, it is not possible to make a definitive conclusion regarding this matter. Cholelithiasis was present in only two patients, and one patient had pulmonary stenosis as a congenital heart anomaly. Horseshoe kidney was detected in one patient with GSD type IV.

It has been previously reported that liver transplantation in patients with GSD is performed to treat liver failure or cirrhosis and that complications associated with GSD may develop after liver transplantation. In a study evaluating 25 patients who underwent liver transplantation, it was reported that three of the patients had GSD type III, and all underwent transplantation due to liver failure [11]. In a study involving eight patients who underwent liver transplantation, it was reported that five of these patients were children, and all received transplants due to cirrhosis. The patients demonstrated a good prognosis following the procedure [38]. Two of our patients also underwent liver transplantation. However, one pediatric patient with type IXc who underwent liver transplantation for cirrhosis died due to complications related to the transplant. The other patient was an adult type III patient. Even though hepatic symptoms improved after transplantation, muscle symptoms progressed.

Patients with hepatic GSD may present with similar clinical findings, such as abdominal distension, hepatomegaly, and elevated AST/ALT/TG levels. While the frequently encountered subtypes vary by region, it has been reported that types III and Ia are the most common in Turkey. The findings presented by the Çukurova University Faculty of Medicine Department of Pediatric Metabolism and Nutrition in the differential diagnosis of GSDs are as follows: In the presence of severe hypoglycemia, GSD types Ia and Ib should be considered; if elevated AST levels are not accompanied by elevated ALT levels, GSD types 0, IXb, and Ib should be considered; and if AST/ALT levels are very high, GSD types III and IXc should be considered. Additionally, severe hypertriglyceridemia in GSD types Ia and Ib, neutropenia in type Ib, and elevated uric acid levels in types Ib and III (except type Ia) were identified as indicative findings in subtype differentiation. Although short stature is a common finding in the early stages, it was observed that most patients who can maintain regular follow-up and treatment reach final heights comparable to the family average.

In the present study, it was noteworthy that the frequency of GSD type Ib was higher compared to type Ia. Additionally, the highest reported number of twin patients in the literature was another notable finding of the study. Intestinal duplication cysts, renal artery stenosis, and pulmonary stenosis were structural anomalies associated with GSD that had not been previously reported. However, due to the high frequency of consanguinity within our cohort, these additional pathologies may be incidental. This study highlighted the increased risk of non-hepatic malignancies in patients with GSD type III for the first time. Therefore, in cases with clinical findings primarily indicative of GSD, such as hepatosplenomegaly, but showing a progressive course, non-hepatic malignancies should also be considered.

In hepatic GSDs, which are common and present challenges in differential diagnosis between types and for which there is no curative treatment approach, sharing clinical data from large case series, along with associated anomalies, complications, and the natural course of the disease, will support the diagnosis and follow-up processes.