Some writers leave behind books. Toni Morrison left behind instructions. And I’m still, quietly, trying to follow them.

Today, August 5, is Toni Morrison’s death anniversary.

The first time I read Toni Morrison, I did not finish the book.

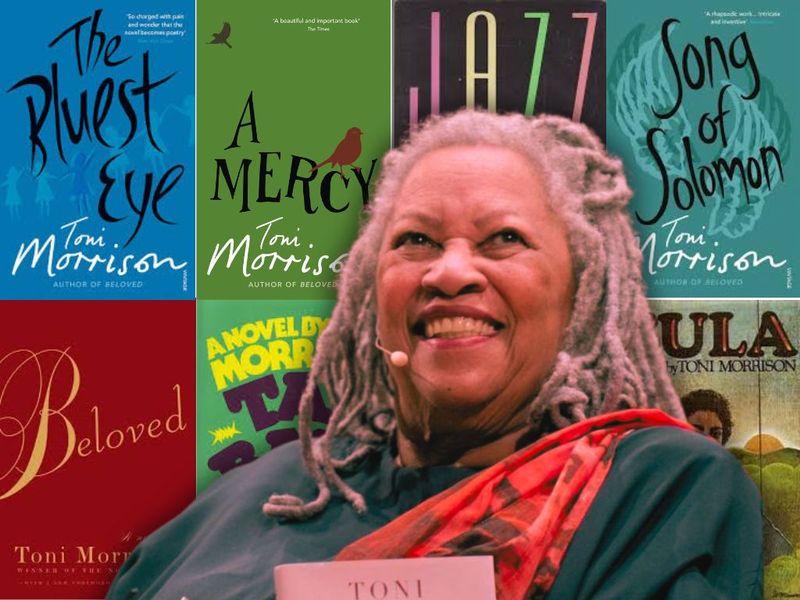

It might have been Beloved, or it might have been A Mercy, try as I might, I cannot get myself to remember.

And that amnesia feels both dishonest and entirely accurate. For a 16-year-old Indian girl, reading about a black woman was a far cry from home. There was no roadmap for me to read an American black woman. No cultural breadcrumb trail. I had space in my malleable brain for only my own inadequacies, and I did not know how to inhabit a world removed from my own.

There were no threads I could pull to stitch myself to the novel. Her sentences confounded me. Her metaphors felt like secrets meant for someone else. Her characters carried centuries in their spines, and I, not yet out of my school uniform, couldn’t yet carry my own history with any grace. I remember flipping back a page to reread a sentence, and then flipping again, and again, until it felt like I was walking backwards in a room with no light. So, I put her down. I have learnt since that Morrison never wrote for the reader who wanted to “get” her. She wrote for the reader willing to meet her, and for that, I wasn’t yet ready. It would take a few years and a slow collapse of the belief that books should make you feel better about the world before I would return to her.

I picked up Toni Morrison again during one of the lowest points in my life and boy, oh boy, was that a convoluted decision. I was unwell in a way that only literature understands. Toni Morrison sticks like melted caramel to the insides of your brain. She festers like a sore and it pains when you least expect it. And yet, you cannot get enough of her.

You see, I made the catastrophic mistake of trying to read The Bluest Eye.

It’s a slim novel. That’s the first thing people notice. You hold it thinking it won’t take you long, but it does; it takes you years, maybe your whole lifetime. I have not finished it. I have tried, three, maybe four times. I’ve underlined passages that felt like they had been written in the house I grew up in. I’ve thrown the book on the floor and cried, tears that fill your mouth and dribble down into your heart.

Also read: Toni Morrison and the Colour of Literature

And yet I stayed. I stayed for the women who held knives in their love. I stayed for the grief that didn’t announce itself but leaked into soup pots and pillowcases, I stayed even though I didn’t understand why.

I have never been able to read her fast. Her books resist speed. They ask to be held, re-read, misunderstood and returned to. You circle back to a Morrison sentence the way you circle back to a bruise. Testing the tenderness. Confirming the pain. Grateful it still hurts.

Morrison lives with you uncomfortably. Or you live with her. Like a guest you didn’t invite, but who starts rearranging your furniture and teaching your bones new names. You emerge from her work with bruises in the shape of questions. She wrote pain with such clarity that you began to suspect she had made a blood pact with it.

There is something feral about grief that has nowhere to go. Mine shows up in the most unexpected of places – a line she once wrote, a song that carries the same salt, a face that looks like it has seen too much too young. Toni Morrison gave me the vocabulary for the things I was too afraid to feel. She also gave me permission to not understand right away.

When she died in 2019, I didn’t mourn her as a literary icon. I mourned her like a stranger who once looked me in the eye and told me a secret I didn’t know I was keeping. Her death felt personal in a way that felt ridiculous at first. She didn’t know me. But her work did. It knew what it meant to be a girl ashamed of her body. It knew the violence of wanting to be loved in the wrong language. It knew how hard it is to live with stories you’re told not to tell.

On her death anniversary, I let the memory of her language breathe in the room, and I carry her name the way we carry the people who cracked us open so something new could enter.

Some writers leave behind books. Toni Morrison left behind instructions. And I’m still, quietly, trying to follow them.

Aashera Sethi is a writer based out of Kolkata, and has a Masters in English that helped fuel a deep love for all things literature.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.